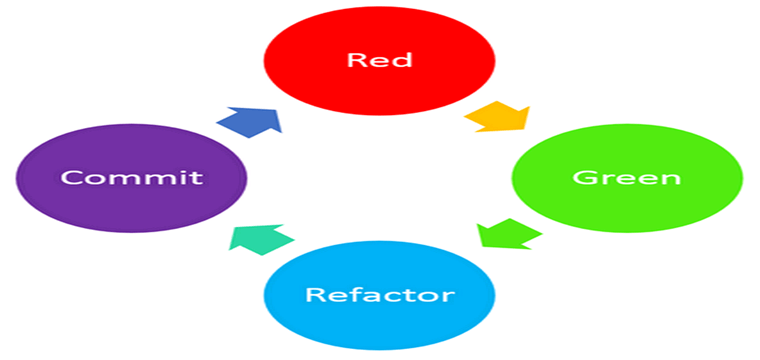

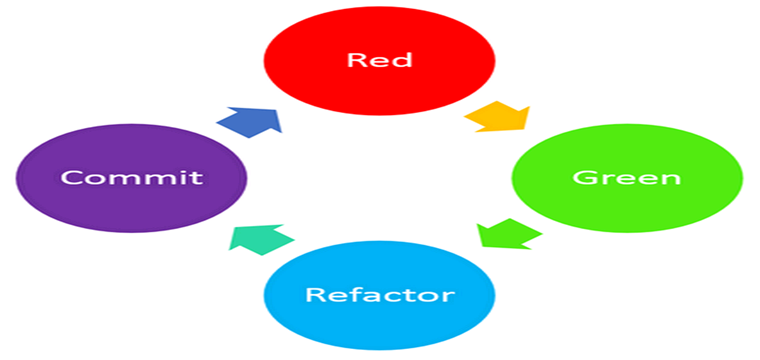

RGRC is the new Red Green Refactor for Test First Development

Date Published: 05 August 2014

Test Driven Development (TDD), aka Test Driven Design, aka Test First Development, has long had a simple, virtuous cycle at the heart of its workflow:

- Write a failing test (run the test(s) – they should be RED)

- Make it pass in the simplest way possible (tests are GREEN)

- Now clean up the code (eliminate duplication and other code smells) (REFACTOR)

When following this workflow, one can make steady, incremental progress on a project or problem with minimal risk of spinning one’s wheels for hours on end or trying to take on too large a task and becoming overwhelmed by its complexity. It’s a great approach that I’ve practiced on countless occasions, and which you can easily practice by performing coding katas. Recently, however, I’ve started making a habit of adding one more step to this process that I think is worth sharing.

Commit Often

Distributed Version Control Systems(DVCSs) have grown in popularity over the last few years, and with good reason. They eliminate a great deal of friction and delay that is generally associated with source control systems. The most popular DVCS system today is Git, but Mercurial(Hg) is also an excellent tool in this space. Recently Microsoft has started supporting Git from within their Team Foundation Server and Visual Studio Online product lines, making it an option in many corporate and enterprise shops that might not otherwise consider it.

When you’re working with a DVCS system, you have access to the complete revision history of your codebase on your local filesystem. With traditional source control systems, any time you check in, your changes are immediately available to everybody else using your source control system. Using DVCS, a traditional check-in is broken up into two parts:

- Commit

- Push

When you commit, you store a set of changes along with a comment in the revision history in your local copy of the source. Nobody else sees this. When you’re ready for your changes to be shared with the rest of the team (also any time you want to ensure your work is backed up somewhere other than your own machine), you push the changes to the central server. There are other patterns and ways of working in a DVCS environment (you don’t have to push to the central server, and in fact you don’t have to get your code from there, either), but that’s the basic scenario.

This makes commits much less expensive to do, in several ways. First, they’re lightning fast. I’ve worked with SVN and TFS version control on remote servers where doing a checkin would take many seconds, during which typically you can’t do anything productive. What’s more, if you’re using a build server and continuous integration, once you check in, you’ve probably triggered a build, which you then should at least keep an eye on passively to ensure you’ve not broken the build. If you do break the build, then your workflow is interrupted, as you must (if you’re taking continuous integration seriously) drop everything and get the build working, since while it’s broken nobody else on your team can use the project’s source code effectively.

In DVCS, you can commitall the time, instantly, without risk of breaking the build or impacting your team. Thus, you should get in the habit of committing frequently. How frequently? Why not commit any time the tests are green and the code is in good shape? That is, right after the Refactor step in your TDD workflow. This results in a new TDD workflow that can be described as Red–Green–Refactor–Commit(RGRC).

Red Green Refactor Commit

Committing after every iteration through the TDD cycle offers a number of benefits. For one, it provides a helpful reminder to commit. Many developers would commit more often if they thought to do so, but since it’s not part of their process, they commit less frequently, perhaps only when they’ve completed a major feature. This reduces the benefit of having a commit history, since if at any point there is a need to revert back to a previous working revision, the average amount of work lost is inversely proportional to commit frequency (i.e. it’s essentially the mean-time-between-commits).

Another benefit of this approach is that your commit history starts to coincide with your test cases. Thus, your commit message can in many cases just refer to the test that you just added, and someone trying to understand what was done in this commit is (or should be) related to the latest test that has been added to the project.

I’ve been using this approach whenever I can (essentially whenever I’m using both TDD and DVCS) and I’ve found it very helpful. Let me know how it works for you, and if you have any related suggestions, in the comments below.

Note: Depending on how complex the refactoring step is you’re about to undertake, you may want to commit before you refactor, as well as once you’re done. That way, if you end up going down a rabbit hole, you can always revert back to your pre-refactoring commit, and still be in a good place with passing tests. I don’t necessarily do this every time, or else I would update this article to use Red-Green-Commit-Refactor-Commit instead of RGRC…

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.