Unit Test or Integration Test and Why You Should Care

Date Published: 19 January 2012

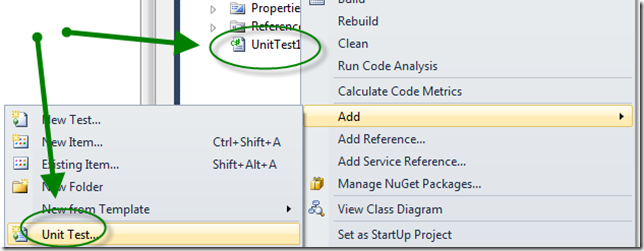

There remains a fair bit of confusion about what constitutes which kind of test. Many developers are fairly new to testing, and tend to call any tests of their code “unit tests” even when they’re dealing with something substantially larger than a unit. The tools don’t really help much here, since the various test runner frameworks all call themselves unit test frameworks, and the various test runners themselves almost universally refer to the tests they run as “unit tests” whether they are or not. For instance, Visual Studio 2010 starts every new Test Project with a class called UnitTest1 and lets you add a new Unit Test, but nowhere does it mention Integration Tests, Acceptance Tests, Smoke Tests, etc, as you use the same code templates to create each of these.

ReSharper and most other add-in test runners follow the same convention – if you ran run it as a test on your code, it’s probably going to be referred to as a Unit Test.

ReSharper 6.1

So what constitutes a unit test, and what constitutes an integration test? What about other kinds of tests beyond these two? There’s a decent StackOverflow answer related to this topic, which lists several kinds of tests and their definitions. Here is what it has to say about Unit Tests and Integration Tests, specifically:

- Unit test: Specify and test one point of the contract of single method of a class. This should have a very narrow and well defined scope. Complex dependencies and interactions to the outside world are stubbed or mocked.

- Integration test: Test the correct inter-operation of multiple subsystems. There is whole spectrum there, from testing integration between two classes, to testing integration with the production environment.

I have my own definition of a unit test, which is that it’s a test that only tests a single path through a single method. More importantly, it’s a test that has zero dependencies on infrastructure, or on code outside of your control. Unit tests should run fast – as in very, very fast – because they aren’t touching file systems, databases, networks, email servers, system clocks, etc. They run your code. Period. If you have code that has dependencies, you need to remove them when running your unit tests, typically by using mocks, fakes, or stubs. I’ve written before about dependencies, if you’re not sure what I mean:

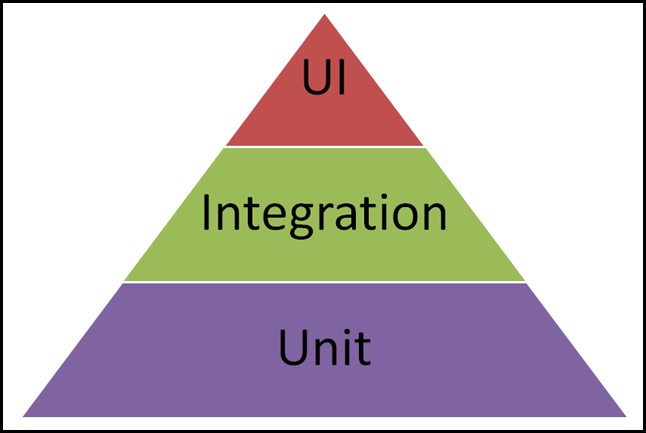

If you have a test that depends on any of the dependencies listed in the above posts, then you have an integration test. Integration tests are great and necessary, but they’re generally at least an order of magnitude slower than unit tests, and as such you’re going to be able to run far fewer of them in a given amount of time. Therefore, you want to write as many unit tests as you can, and write integration tests for things unit tests can’t do (like actually testing your infrastructure and interactions between components). Basically, you want to follow the Test Pyramid, just like in the United States people are encouraged to eat based on the Food Pyramid (with one key difference being that the Test Pyramid is probably better advice and is less controversial).

Basically, you want a lot more servings of Unit Tests in your daily diet than Integration Tests, and remember that UI tests, being the most expensive and usually the most brittle, are a sometimes food.

How Can You Tell if a Test is a Unit Test or an Integration Test?

Here are some quick questions you can use to qualify your tests. There may be some exceptions to these rules, but these are generally good guidelines. It’s usually a good idea to separate your unit and integration tests, either as separate projects/assemblies, or at least using separate categories, so that you can run them separately. You’ll want to run the unit tests all the time, and they should be fast enough that doing so isn’t too painful. You’ll want to run the integration tests as often as you can bear to do so, but often these take long enough to run that you don’t want to run them with every compile or before every check-in.

Q: Does the System Under Test (SUT) require an installed and configured and available database in order to run the test successfully?

A: If yes, then it’s an Integration Test

Q: Does the SUT talk to the file system?

A: If yes, then it’s an Integration Test

Q: Does the SUT reference configuration files directly?

A: See previous question. It’s an Integration Test.

Q: Does the SUT reference a service over the network?

A: If yes, then it’s an Integration Test

Q: Does the test take more than 10ms to execute?

A: If yes, it’s very likely an Integration Test, or at the very least it may be possible to refactor it to run faster.

Q: Does the SUT send emails as part of the test execution, even via a local SMTP server like smtp4dev?

A: If yes, then it’s an Integration Test.

Q: Does the SUT depend on the system clock? Are there certain days of the week or times of day when it would behave differently?

A: If yes, then it’s an Integration Test.

Q: Does the test make use of a mocking framework?

A: If yes, then it’s likely a Unit Test. Generally you shouldn’t need to mock much in your integration tests, or you risk not actually testing your system.

References

MSDN describes Unit Testing and Integration Testing if you’d like an “official” Microsoft source

“What is Unit Test, Integration Test, Smoke test, Regression Test?”

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.