Thread.Sleep in Tests Is Evil

Date Published: 22 April 2016

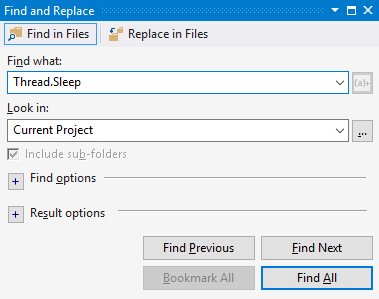

Do you have calls to Thread.Sleep in your test code? If you’re not sure, you can easily find out by opening up the project in Visual Studio and running Find in Files (ctrl-shift F):

Thread.Sleep will, not surprisingly, dramatically slow down your test suite. The primary reason is that it’s waiting longer than it has to, every time. Consider an example. You have an integration test that depends on an API call completing successfully. Usually the call takes a hundred milliseconds or so, but sometimes it takes a couple of seconds. You don’t want to have your test fail just because the call was a little slow, so you make sure it only fails when something is really wrong by adding

Thread.Sleep(5000); // sleep 5 seconds

This falls into the “better safe than sorry” category and at least lets you avoid having a test that intermittently fails for no apparent reason. But it makes your test suite slow. If the call usually takes 100ms and you are waiting 5000ms every time, this test is now 50 times slower than it should be in the typical case. Instead of forcing your test to always wait a certain amount of time, you should write the test so that it waits up to that amount of time, but if the thing you’re waiting for happens, stop waiting!

Using ManualResetEvent

The ManualResetEvent lets you communicate between your asynchronous or multi-threaded code and your unit test. There are three simple steps to using ManualResetEvent in your test code.

- Create the ManualResetEvent; pass false to its constructor – this indicates the signal you’re waiting for hasn’t yet been sent.

- Trigger the event when your async code completes by calling .Set()

- Wait to Assert in your test until the signal (Set is called) by calling WaitOne(). You can optionally supply a timeout.

As a simple example, consider a case in which your test code needs to trigger an event that occurs on a separate thread, and then wait to ensure the callback occurs. One approach to this would be to trigger the event, then Thread.Sleep, but as I’ve already pointed out this is an evil antipattern. Instead, look at the following code, which tests the MemoryCache object in ASP.NET Core:

public class MemoryCacheRemove

{

private readonly MemoryCache _memoryCache;

private readonly string _cacheItem = "value";

private readonly string _cacheKey = "key";

private string _result;

public MemoryCacheRemove()

{

_memoryCache = new MemoryCache(new MemoryCacheOptions());

}

[Fact]

public void FiresCallback()

{

var pause = new ManualResetEvent(false);

_memoryCache.Set(_cacheKey, _cacheItem,

new MemoryCacheEntryOptions()

.RegisterPostEvictionCallback(

(key, value, reason, substate) =>

{

_result = $"'{key}':'{value}' was evicted because: {reason}";

pause.Set();

}

));

_memoryCache.Remove(_cacheKey);

Assert.True(pause.WaitOne(500));

Assert.Equal("'key':'value' was evicted because: Removed", _result);

}

}The above test provides a lambda expression for the callback that has access to the ManualResetEvent, pause. Calling its Set method will immediately cause the call to WaitOne to return true. If the timeout value provided to WaitOne (500ms in this case) is reached, it will return false. In this way, the test never waits longer than it needs to for its dependent multi-threaded code to execute. You can see several more examples like this one in thedocumentation of ASP.NET Core MemoryCachethat I authored.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.