Refactoring to Value Objects

Date Published: 07 September 2021

Value Objects are a part of Domain-Driven Design, and Julie Lerman and I cover them in our DDD Fundamentals course on Pluralsight. Even if you're not applying Domain-Driven Design to your application, you can take advantage of refactoring your business classes to avoid code smells like primitive obsession (follow the link for more on refactoring and code smells). To demonstrate this concept, I'm going to show a simple class as it might start out, and then show how I would refactor it.

(This is actually based on a conversation I just had with one of NimblePros' clients. I figured I might as well share my thoughts more broadly than just with that team! The actual types have been changed, but the principles can be applied generally.)

An Employee Entity

The following code listing shows an entity for modeling employees in an application.

public class Employee

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public DateTime StartDate { get; set; }

public DateTime? EndDate { get; set; }

public string Address1 { get; set; }

public string? Address2 { get; set; }

public string City { get; set; }

public string State { get; set; }

public string PostalCode { get; set; }

public string Country { get; set; }

public Employee(string firstName, string lastName, DateTime startDate,

string address1, string city, string state,

string postalCode, string country, string? address2 = null)

{

FirstName = firstName;

LastName = lastName;

StartDate = startDate;

Address1 = address1;

City = city;

State = state;

PostalCode = postalCode;

Country = country;

Address2 = address2;

}

public override string ToString()

{

string name = $"{FirstName} {LastName}";

string dates = $"{StartDate.ToShortDateString()}-{EndDate?.ToShortDateString()}";

string address = $"{Address1}\n{Address2}\n{City}, {State} {PostalCode}\n{Country}";

return $"{name}\n{dates}\n{address}";

}

}This class shows an entity, meaning it has some identity. In this case it's using an integer ID property. It's also using the latest C# nullable reference types, so all non-null properties are passed in through its constructor. It works with the latest versions of EF Core, which can use the constructor to provide primitive values to properties based on conventions. However, even though this is just a simple demo, it has a lot of properties that are obviously related to one another. To wit, the first and last names go together, the employment dates go together, and the address fields go together. We know this because we have some idea of the domain, and the author of this class is helping us see these relationships by ordering and grouping the related properties using whitespace. But none of this information is embedded in our model - our type doesn't care about the ordering or grouping of these properties. They're just a bunch of strings and DateTime types.

It's worth briefly noting that all of these properties have public setters. In a real app with any amount of encapsulation this wouldn't be the case. But one other thing to note that's related to the primitive obsession and lack of abstraction is that any enforcement of rules related to these properties must be dealt with in the Employee class.

For example, a fairly obvious rule might be that if an Employee's EndDate has a value, that value must be greater than (or perhaps equal to) the Employee's StartDate. With public setters this is pretty difficult to enforce, but even if we make the setters private and add methods for updating the Start or End date, the fact remains that this logic now lives in the Employee class. Should the Employee class concern itself with low level concerns like whether two dates make sense together? Is this an employment rule, or is it a general rule of how date ranges with starts and ends are expected to behave? I'd argue it's more the latter.

Add a DateTimeRange Value Object

In the veterinary clinic sample for my Pluralsight course, which is available on GitHub, we introduce a DateTimeRange value object class. We use it to describe appointments, but it's obviously a general purpose concept that could be used to describe any period with a start and an end date (modify it if needed to describe things that don't yet have an end date, such as current employment period).

So what exactly is a value object? Simply, it's a class whose instances are compared using only their current state. In the framework, String and DateTime are both examples of value objects. It's also worth noting that a value object isn't so much a thing on its own, as it is a way of describing something in the domain. If I just tell you "7 September 2021" (as a DateTime) with no other information, you know that's a date, but it's otherwise meaningless. You're left wondering "what about it?". But if I tell you the Article with ID 123's PublicationDate was 7 September 2021, now that has some meaning in your domain model.

Another quality of value objects should be that they are always in a valid state. Think about the built in DateTime type. Do you ever have to check whether its month or day values are out of range? Of course not, because if you were to try to create an instance with out of range values, it would throw an exception rather than give you an invalid instance. What this characteristic means is that we can compose our entities of value objects and eliminate a lot of the boring "does this object state make sense" code from our entities and instead put that into value objects which must be created in a valid state. They're also immutable so if they're created in a valid state, you know they're going to stay that way. More on the details in the course.

So, once we add a DateTimeRange to the class, we replace the StartDate and EndDate properties with just one property.

public DateTimeRange EmploymentDates { get; set; }Add a Name Value Object

In many applications, names exist on a variety of entities. Even if they only ever exist on a single entity, it can still be useful to pull the primitive set of strings out and encapsulate them in their own value object (for the reasons listed above). In many apps, name will include things like Title, Salutation, First, Last/Surname, Middle, Suffix, etc but in this simple example it's just First and Last. So what would a Name value object that represents these values look like? Well, assuming they're both required (no support for "Madonna" or "Beyonce" or "Bono" here) you might have something like this:

public class Name : ValueObject

{

public string FirstName { get; private set; }

public string LastName { get; private set; }

public Name(string firstName, string lastName)

{

FirstName = Guard.Against.NullOrEmpty(firstName, nameof(firstName));

LastName = Guard.Against.NullOrEmpty(lastName, nameof(lastName));

}

public override string ToString()

{

return $"{FirstName} {LastName}";

}

protected override IEnumerable<object> GetEqualityComponents()

{

yield return FirstName;

yield return LastName;

}

}This class is using a base type provided in the CSharpFunctionalExtensions package, which handles equality checking by exposing an abstract list of properties to compare (the GetEqualityComponents method). If you're wondering why one doesn't just use C# records for value objects, the biggest issue is their support for the with keyword, which effectively lets you bypass all of the validity checks the constructor performs. More on why records aren't quite good enough to use as value objects here.

Now, looking at the Name class you can see that it accepts all of its state through its constructor, it ensures the values are not null or empty (using the Ardalis.GuardClauses package), and it's immutable since it doesn't expose any way to alter its state. All value objects should have these characteristics.

After making this change, the FirstName and LastName properties can be replaced:

public Name Name { get; set; }Add an Address Value Object

By now you should get the idea. An address representing a mailing or shipping address is a very common candidate for a value object. There are many minor differences in how one app or another might choose to represent an address. How many lines for the top of the address (I've seen as many as six!)? Use an abbreviation string for the state, or a foreign key id to a State lookup table? Same for country. How well should the entity represent addresses of various different countries or locales? Etc. However if you already have made all of these decisions, as we have in this case, and you have a stack of primitive properties representing an address, it's easy to take those and convert them all into an Address value object (and if you have a bunch of these primitives more than once, such as for Billing and Shipping, then you seriously should use value objects instead).

Here's an Address value object taken from the original Employee class above:

public class Address : ValueObject

{

public string Address1 { get; private set; }

public string? Address2 { get; private set; }

public string City { get; private set; }

public string State { get; private set; }

public string PostalCode { get; private set; }

public string Country { get; private set; }

public Address(string address1, string city, string state,

string postalCode, string country, string? address2 = null)

{

Address1 = address1;

City = city;

State = state;

PostalCode = postalCode;

Country = country;

Address2 = address2;

}

public override string ToString()

{

return $"{Address1}\n{Address2}\n{City}, {State} {PostalCode}\n{Country}";

}

protected override IEnumerable<object> GetEqualityComponents()

{

yield return Address1;

yield return Address2 ?? "";

yield return City;

yield return State;

yield return PostalCode;

yield return Country;

}

}With this type, the original property on Employee now just looks like this:

public Address Address { get; set; }Ok, so what about these public setters on these entity properties? You probably should still avoid exposing setters directly most of the time, as this can lead to an anemic model and code that violates the Tell, Don't Ask principle. However, if the only reason you wanted to expose custom methods for updating these properties was to ensure they were valid in the context of the other properties, you might not need that anymore since the value objects already perform this check for you. Thus, your code is more robust simply because you moved to using value objects, even if you don't put any additional effort into protecting the encapsulation of your entities (though again, it's probably still a good idea).

Persisting Value Objects

You might be wondering what persistence looks like with value objects. If you're using EF Core, what is it going to do with these custom types on these entities? Fortunately, EF Core has had support for something called owned entity types for a while now. All you need to do to make these work is configure your entity, telling EF Core that a particular property of a particular type is owned by the entity, like this:

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder)

{

base.OnModelCreating(modelBuilder);

modelBuilder.Entity<Worker>()

.OwnsOne(w => w.Name);

modelBuilder.Entity<Worker>()

.OwnsOne(w => w.Address);

modelBuilder.Entity<Worker>()

.OwnsOne(w => w.EmploymentDates);

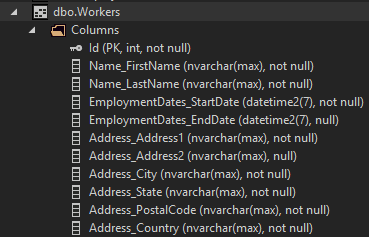

}What does this look like in the database? All of the properties are still stored in the same table as the owning entities, but a naming convention is used such that the column names are prefixed with the entity's property name. So instead of columns FirstName and LastName, you have columns Name_FirstName and Name_LastName.

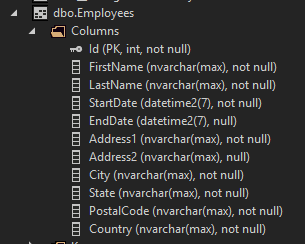

Here's what the original Employee class's backing database table looks like:

And here's what the refactored class (which I renamed to Worker) looks like:

Note that you never need to use .Include() to bring in owned entity types. They're always loaded since they're on the same record as the owning entity.

The Refactored Version

After refactoring the original Employee class to replace loads of primitive properties with three value objects (and moving its Id property to a BaseEntity) the new version looks like this:

public class Worker : BaseEntity

{

public Name Name { get; set; }

public DateTimeRange EmploymentDates { get; set; }

public Address Address { get; set; }

public Worker(Name name, DateTimeRange employmentDates, Address address)

{

Name = name;

EmploymentDates = employmentDates;

Address = address;

}

#pragma warning disable CS8618 // Non-nullable field must contain a non-null value when exiting constructor.

private Worker() { } // EF

#pragma warning restore CS8618 // Non-nullable field must contain a non-null value when exiting constructor.

public override string ToString()

{

return $"{Name}\n{EmploymentDates}\n{Address}";

}

}There are only three properties, which also means the constructor is much shorter. Methods with more than 5-7 parameters are another code smell to watch out for. Remember, code smells aren't always bad, but they're worth looking at to see if they're bad. By replacing lots of primitives with higher level abstractions in the form of value objects, we've simplified our entity and its constructor significantly. Notice that even the ToString() method got simpler, because it's able to rely on the underlying types' implementations.

If you'd like to get better at this sort of thing, and you have a Pluralsight subscription, check out my courses I've linked here. Otherwise, consider joining my group coaching program devBetter, where we discuss things like this every week. And of course, books like Refactoring and Working Effectively With Legacy Code are great resources as well*. If you found this helpful, I hope you'll share it with a friend. Thanks!

*Affiliate links help support my blog without costing you any more.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.