Code Analysis Techniques

Date Published: 17 August 2010

There are a number of code analysis tools available for .NET developers, including some stats that are built into the pricier SKUs of Visual Studio. Recently, I’ve been playing with a relatively new product (released earlier this year by Microsoft agile consulting shop NimblePros.com) called Nitriq. Nitriq is a bit like LINQPad for your code. If you’re not familiar with it, go download LINQPad now – it’s a great tool worth paying for. I’ll wait until you’re back…

Back? Great! I think we were discussing using Nitriq for code analysis, which by the way you can run for free on a single assembly. Before going any further, it’s worth mentioning something that many of us often forget or perhaps never learned, and that is that code is data. Some languages, like Lisp, make it very easy to manipulate code as if it were data (and vice versa), but even in static, managed languages like C# it is worth remembering that our code itself is data that we can query, analyze, and from which we can learn.

So before we go any further, what kinds of questions might we ask of our code? One of the best use cases for such code analysis is to find code smells, anti-patterns, and other things that would generally indicate a lack of quality. Static Cling is one-such anti-pattern I’ve described previously that it would be great if we could detect it.

Static Methods That Instantiate Objects

-

var results = from m in Methods let ConstructorCalls = m.Calls .Where(callMethod => callMethod.IsConstructor) .Count() where m.IsStatic && !m.IsConstructor && ConstructorCalls > 0 select new { m.MethodId, m.Name, m.FullName, ConstructorCalls };There’s nothing inherently wrong with static methods from a testability and code quality standpoint provided they are leaf nodes in your object graph. It’s when they start newing up objects that things tend to become tightly coupled and you start down the path toward the Big Ball of Mud architecture. So, being able to find static methods that instantiate objects would be a worthwhile query to run. It’s likely there are a few static methods that deserve to be made into instance methods on classes, and whatever objects they’re instantiating could probably be passed into the method or the new class’s constructor using dependency injection. (I’m a big fan of keeping things loosely coupled by explicitly declaring dependencies – if you’re interested I have a few posts on dependencies).

I know from experience that finding these kinds of static methods and cleaning them up is a very worthwhile exercise and will result in a better system. The time to clean it up is usually either when you have some extra time in an iteration, or when you’re already touching the code in question – I don’t generally advocate spending large amounts of time purely on cleanup. Customers like to see fixed bugs and new features, and delivering customer value needs to be the top priority. But being able to maintain the ability to deliver that value requires keeping our codebase tidy – so clean up these dust bunnies when you encounter them.

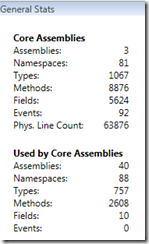

General Stats

The code I’m running Nitriq on at the moment has the following stats (see image at right). I’m analyzing 3 related assemblies in an ASP.NET web forms application. You can see that these 3 “core” assemblies being analyzed have a total of 81 namespaces, 1067 types, 8876 methods, etc. The total physical line count is about 64k. These assemblies call other assemblies that aren’t included in the analysis, including third party DLLs and of course the .NET framework itself. All told, that includes another 40 assemblies and another 2608 methods that aren’t directly included in the analysis, but are used by my assemblies.

Running the query above to seek out static methods that instantiate objects, I get 228 such methods. This works out to about 2.5% of the total codebase, which is pretty small, but in looking at the actual methods returned I immediately recognize several that I’ve struggled to test or refactor in the past, so I know I can make it better.

Trouble Methods

A number of computer science papers have linked cyclomatic complexity and line count of methods and files to the number of bugs occurring in these methods or files. More recently, some papers have attempted to link design flaws with defect incidence, with some success[1]. There Naturally if the likelihood of bugs per lines of code is constant, one would expect there to be more of them in longer files than in shorter ones, but in fact the bug rate per line of code increases with the length of the file[1]. Unfortunately, accurate prediction of software defects is a difficult problem, as this 11-year-old IEEE Critique of Software Defect Prediction Models indicates[2]. But until we have better tools, it remains useful for us to attempt to keep our code neat, clean, and as simple as possible (but no simpler).

One of the design flaws noted in D’Ambros’ paper is Dispersed Coupling, which relates to the number of other types used by a particular class (or method). We can pull out this information, along with other useful data points like LOC, cyclomatic complexity, and parameter count using the following LINQ query against our code:

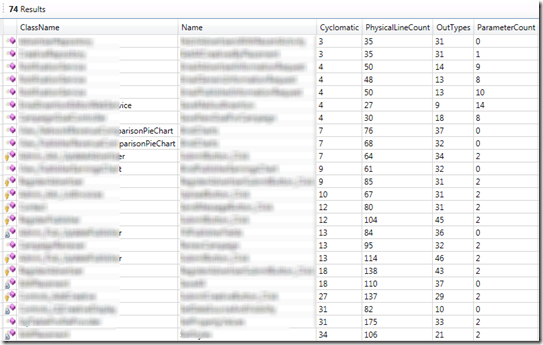

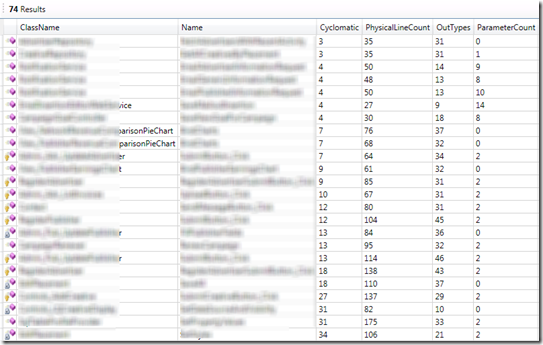

Methods to Refactor

var results = from method in Methods where (method.Cyclomatic > 25 || method.PhysicalLineCount > 200 || method.TypesUsed.Count > 30 || method.ParameterCount > 7 && method.Type.IsInCoreAssembly select new { method.MethodId, method.Name, method.Cyclomatic, method.PhysicalLineCount, OutTypes = method.TypesUsed.Count, method.ParameterCount };Obviously we can tweak the values we’re interested in filtering out, but the above results in 74 results in the system I’m working with. Here’s an example of the results:

I’ve sorted the results by Cyclomatic in this case, which I like to keep as low as possible. Out of almost 9,000 methods, having only about a dozen that have a 10 or higher CC score isn’t too awful, but again the ones at the bottom of this list are almost all (the exception being one generated code file) the nastiest classes in this system. They really should each have a giant header comment saying “Here there be dragons” to warn any who enter them. So, that tells me that this analysis, at least anecdotally and at the extremes, is worthwhile and able to locate “smelly” areas of my codebase.

Once you know where the piles of crap are in your code, it makes it much safer for you to walk through it without getting dirty or spreading the smell around too much (how’s that for a metaphor?). And of course, knowing where these festering piles of poo are means you can go and clean them up later. If they’re tough to refactor, pick up a copy of Working Effectively With Legacy Code to help you introduce seams that will make the work easier.

More Complex Queries

Another code metric one can apply is the Henderson-Sellers Lack of Cohesion metric. This takes on the following form:

The intuition underlying the Henderson-Sellers method of calculating Lack of Cohesion of Methods (LCOM) is that in a cohesive class C, many methods access the same fields of C. Formally, let

- M = set of methods in class

- F = set of fields in class

- r(f) = number of methods that access field f

- ar = mean of r(f) over f in F

We then define LCOM of the class under consideration to be

LCOM = (ar – |M|) / (1 – |M|)

A value greater than 0.9 is thought to merit investigation. Even a relatively complex metric like this can be converted into a LINQ query fairly easily:

Henderson Sellers Lack of Cohesion of Methods

var results = from type in Types let methodCount = type.Methods.Count let instanceFields = type.Fields.Where(f => !f.IsStatic) let fieldAccesses = instanceFields.Select(f => f.GotByMethods.Union(f.SetByMethods).Distinct() .Where(m => m.Type == type).Count()) let accessAverage = fieldAccesses.Count() == 0 ? 0 : fieldAccesses.Average().Round(2) let lcomHS = ((accessAverage - methodCount) / (1 - methodCount)).Round(2) where lcomHS > .9 && instanceFields.Count() > 0 && type.IsInCoreAssembly orderby lcomHS descending select new { type.TypeId, type.Name, lcomHS, methodCount, fieldCount = instanceFields.Count(), accessAverage, type.FullName };[More on LOC-HS in the eclipse-metrics project on sourceforge]

In an ASP.NET application, a lot of ASP.NET Pages come back with values of 2 for this and can be safely ignored. A quick and dirty way to do this in my project, since the web project is called “Foo.Web” is to add this to my where clause:

&& !type.FullName.Contains("Web")That drops the number of results from 343 down to 119 – about 2/3 of the problems (and all of the ones with an lcomHS score of 2). What remain are classes that, again, are generally worth looking at to see if they have design issues that should be addressed at some point.

Code Audits

Depending on your vertical industry, it may be worthwhile to have your code and/or architecture audited by a third party. NimblePros, the company responsible for Nitriq, also offers such audits, as do a number of other reputable companies with which I’m familiar (and happy to recommend if contacted privately). Code audits can provide a relatively inexpensive way to insure for non-technical or management stakeholders that the code being produced by contractors meets a certain quality bar. Especially in the situation of government contracts, which are typically awarded to low bidders, some kind of independent check on quality should be a no-brainer to prevent waste (assuming of course the project wasn’t awarded to the governor’s teenage kid or something similar to begin with).

Leaving aside contractors, in-house development projects can often benefit from code audits as well, which typically include architecture, performance, security, and more. The perspective of an outside authority can often uncover design decisions that represent “low hanging fruit” and can quickly and easily be adjusted to produce a much better solution. Sometimes the hard part really is just knowing where the problem is – after that fixing it is easy. That reminds me of a story I heard somewhere a long time ago, that I’ll wrap up with:

The Engineer Turned Consultant

Once upon a time there was an engineer who worked his entire career at a manufacturing plant, and then ultimately retired. One day, the huge and expensive machinery responsible for the plant’s ongoing production broke down. The staff tried to fix the problem, but hours turned into days without success, and the continued downtime would cost the company millions if not rectified swiftly. The company called in the old engineer, who inspected the machine carefully for some time, then marked a particular part with a piece of chalk and said “Replace this part.” The factory staff did as he recommended, and in no time the plant was back up and running.

Not long after, the company received a bill from the consultant-nee-engineer for $50,000. Shocked, they demanded an explanation and breakdown of this expense. The engineer responded:

Piece of Chalk $1.00

Knowing What To Mark With It $49,999.00

I’ve always liked that story. The chalk wasn’t the real value the engineer was brought in to provide, after all.

References

[1] *On the Impact of Design Flaws on Software Defects,*D’Ambros, Bacchelli, Lanza

[2] A Critique of Software Defect Prediction Modules, Fenton

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.