Use Write Caching to Optimize High Volume Data Driven Applications

Date Published: 04 April 2005

Scenario

For the past several years, I’ve been running a small online advertising network which, as I write this, serves about 50 million ads per month. A requirement of this application is that impressions and clicks be tracked so that my customers can evaluate the results of their campaigns. My system uses a SQL Server database that is located on a dedicated server on the same network as my clustered web servers (hosted at ORCSWeb). In this situation, there are dozens of requests per second that must be tracked and persisted to the database, not to mention the requests for data to actually serve the ads. This kind of activity logging is an example of a high volume database operation which can be optimized through the use of caching and batch updating.

In the simplest case, every request for data can be fetched from the database, and every incremental change in statistics can be written back to the database, either as a series of INSERT statements or a combination of INSERT and UPDATE statements. Assuming a fast network connection and a properly tuned database, this can perform quite adequately up to a volume of transactions. However, applying some caching, even for just a brief instant, both for the necessary reads as well as the writes, can dramatically boost the overall performance of the application.

The Problem

The basic problem in this scenario is how to persist data to the database without slowing down the web application, but with minimal risk of losing the data (e.g. if a web server crashes). As for reading the data required for the application in an efficient but timely manner, this is a perfect candidate for micro-caching, which I describe in a previous article. When approaching this problem, one can come up with a variety of options for how to log each unit of work:

A. Direct to the database - INSERT to a log table - periodically push from the log table to a summary table

B. Direct to the database - INSERT item into summary table if needed - UPDATE to increment summary table counter thereafter

C. Increment counter in memory - push to database periodically

D. Increment counter in file system - push to database periodically

E. Use MSMQ to queue updates

The benefit of Option A is that each insert will be very fast, and there shouldn’t be any locking on the table except when the move to the log table is done. With Option B, there will be some lock contention while updates are performed, but only on a per-item (row) basis. The whole table is (typically) never locked*, so the locks will only be in contention if a particular row is seeing a very large amount of activity. Both options share the advantage of being reliable, in that data is immediately persisted to the database. However, they also share a related disadvantage, in that they impose a steady load on the database.

*It is possible for locks to be escalated to table locks, as this article describes. However, one can avoid this possibility by using techniques described in the article, or by adding WITH ROWLOCK to the INSERT/UPDATE statement. Generally, though, it is best not to do this, as SQL Server will usually choose the right kind of locking our interference (test your system with and without and see if it makes a difference – if not, leave WITH ROWLOCK off).

Option C, combined with data persistence using either option A or B’s technique, removes some of the database load but at the expense of some data volatility. The two are inversely related--the more I reduce the load on the database, the more data I risk in the event my application crashes or restarts. Since server restarts are somewhat rare but certainly not unheard of in my experience (individual web applications might restart daily or once a week, depending on how often they’re being updated, or if the application pool is set up to automatically restart), it is best to keep the cache window fairly small. Since by definition these high volume applications are writing to the database many times per second, a one second period is a good starting point (and further increases tend to have greatly diminished returns).

Option D I added just for completeness. I would not recommend this system. For one thing, in my scenario, my web farm uses a shared file system, so there would be contention for the file(s) used for logging. For another, this would simply trade the bottleneck of database access for the bottleneck of file system access. It would have the benefit of persisting data between app restarts, but I don’t think this advantage makes up for the disadvantages. As with Option C, the data in the file(s) would be persisted to the database periodically using either of the methods described in options A and B.

Option E would probably work best in an enterprise scenario where it is critical that no data be lost. I did not attempt to implement this scenario because I didn’t have any prior knowledge of MSMQ. But I did find this article, which would appear to offer a good start for anyone wishing to go down this path. AppLogger Using MSMQ also looks like it would be worth checking out. Perhaps I’ll examine this option in a future article.

For now, let’s revisit options A and B. Why choose one versus the other? I’m assuming in the way I’ve described these tables that I’m going to need a summary table. Basically, my application will log several million hits per day, so it makes sense to me to summarize these rather than add several million rows of data per day. That still leaves the question of when to summarize. In the case of option A, the writes are all INSERTS, and the summary table is only updated from the log table periodically. Option B uses a combination of INSERT and UPDATE statements to eliminate the need for the log table by always writing directly to the summary table. I haven’t done any benchmarking of option A versus option B, but my gut tells me that option A will be faster, because inserting to the end of a table is pretty much always going to beat doing an update somewhere in the middle of a table (not to mention that UPDATEs are, generally, more expensive than INSERTs).

However, I like the simplicity of option B, as it requires fewer tables and does not introduce the need to periodically clean out the log table. Also, the data in option B’s summary table is always current (or at least as current as the last update from the web application). Option A’s summary table will never show real-time data, since it depends on infrequent updates from the log table. This may not be a problem in many applications, but in my case I’m already introducing some lag time with my caching on the web server, so I don’t need any further delays on the database.

That said, my preference is clearly C/B. My database structure is going to consist of a summary table to which I’ll log activity using a combination of INSERTs and UPDATEs, and I’ll cut down on how often I need to hit the database by implementing some in-memory counters on the web server. At this point, I just have a ‘gut feeling’ that the option C is going to help compared to simply hitting the database directly (option B). Let’s run some tests.

Test: No Caching - Nothing but DB

I ran two separate tests of my application using Microsoft Application Center Test. The test script simply loads a single page. That page displays several advertisements, and some other data-driven information. Without any caching, each page view involves five database calls:

-

Pull information about the page itself

-

Pull collection of ads to show (always 3 in this test)

3-5) Log one impression for each advertisement

The two test cases vary only in the location of the database. In the first case, the web server and database (and test client) were all located on the same machine. In the second case, the database was offloaded to a separate machine on the same LAN. All of these tests involve a single user (1 browser connection), no delays or sleep time, 30 seconds of warm-up, and a 5 minute test period (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ACT Test Settings

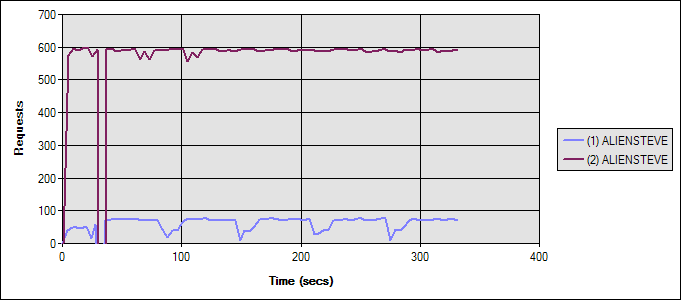

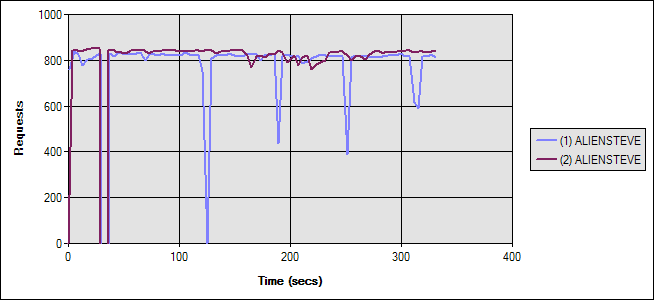

The results of the two tests were dramatically different. I monitored the network during the tests, and it was nowhere near capacity, so I have to conclude that the difference in requests per second stems from the millisecond delays incurred by the network latency. Figure 2 shows the two tests. The blue line (1) represents the case where the database was on a separate server. The magenta line (the much higher one) represents the case of everything on one box. The requests per second include several image, CSS and JavaScript requests per page – actual ASP.NET page requests is actually 1/7th of the total requests per second.

Figure 2: No Caching; Comparing Local Database (Magenta) with Separate Database (Blue) Test Run Graph

(ALIENSTEVE is the name of my AlienWare laptop)

More Details

Test 1 (Blue) averaged 9.14 ASP.NET requests/second. Test 2 averaged 84.15 ASP.NET requests/second. For test 1, the web server’s CPU averaged just 12% -- obviously it wasn’t the bottleneck. For test 2, the web server (also the db server in this case) CPU averaged 69% (still not maxed out, but a dramatic difference). Average Time to Last Byte (TTLB) in Test 1 for each whole page was 103ms. For Test 2 it was just 7ms.

Looking at the database, in Test 1, the remote database averaged 91.86 Batch Requests/sec. In Test 2, the local database averaged 420.74 Batch Requests/sec.

Test - Cache Reads, Not Writes

In this interim test, I’m again comparing a local database with a remote database while modifying the application so that the reads on the page are cached. Reads represent 2 of the 5 database calls made per page and are being cached for 5 seconds. The reason for this interim step is mainly due to the fact that when most people think of caching, they think of read caching. Almost all write operations in data driven applications (that I’ve worked with) are immediately persisted to the database. Most applications do a lot more reading than writing, too, so there are clearly greater gains to be made by caching the former than the latter in most applications. Since it represents the ‘typical’ scenario, it’s included here for comparison.

Figure 3 shows the two scenarios. Once again, the blue line shows the first test with the remote database, while the magenta line shows the second test with everything on one machine.

Figure 3: Read Caching Enabled Test Run Graph

As you can see, the difference between local and remote databases is still huge. Both tests performed marginally better than in the no-caching scenario, showing some benefit to adding the caching. In fact, were it not for the huge difference in performance between the local and remote databases, the addition of the caching would certainly be looked upon as a major improvement, since requests per second between them increased 50% for the remote database case when caching was added.

More Details

Test 1 (Blue) averaged 13.85 ASP.NET requests/second. Test 2 averaged 95.36 ASP.NET requests/second. For Test 1, the web server’s CPU averaged 14%. For Test 2, the web server CPU (and also the db server in this case) averaged 70%. Average Time to Last Byte (TTLB) in Test 1 for each whole page was 67.43ms. For Test 2, it was just 5.66ms.

Looking at the database, in Test 1, the remote database averaged 84.54 Batch Requests/sec. In Test 2, the local database averaged 286.49 Batch Requests/sec.

My editor wondered if perhaps part of the difference between local and remote databases was due to using named pipes instead of TCP/IP stack. I ran the local test again, forcing the connection to go through TCP/IP, and the results were unchanged. In order to do this, I altered the connection string so that the server was referenced by IP (127.0.0.1) and added “Network Library=DBMSSOCN.”

Write Caching, or Batch Updating

Before moving to the next set of tests, let’s talk about write caching, batch updates, or whatever else you’d like to call it. In the typical read caching scenario, the database holds the most accurate picture of the actual data, and the application maintains a separate, potentially less-current copy of that data that it periodically updates. With write caching, these roles are reversed--the web application holds the most current version of the application data, or at least the most current piece of it. The database has an older version of the data, or an older subset of the data. Implementing write caching in a data driven .NET application can be done in a number of ways.

Two mechanisms are needed to implement write caching: a method of storing the updates within the application and a method of persisting the updates to the database. Earlier I compared storage of the data in memory versus on the file system and decided that my preference is in-memory storage. Once that decision has been made, there are still many ways to go about implementing the in-memory storage of the data. This will depend to some extent on how detailed is the data being logged.

When I first began, I started with a very simple Application variable, which I incremented with each request. This worked okay, until I decided I also needed to track clicks separately, for each advertisement and by date. Once I started needing multiple counters, I decided it was time to break down and implement my own classes to perform the in-memory storage of the update data.

Storing Update Data in Memory

Actually, my next step was to set up two Hashtable collections, one for clicks and one for impressions, each holding an integer value keyed off of a date plus an advertisement ID key. This would have worked, but since both sets of data are destined for the same database table, it would have required me to reconcile the two sets of counters prior to persisting to the database, or else required a lot of duplicate database calls.

So then, finally, I created an Activity class to hold the ID, date, impressions, and clicks, and then I created a 1400-line strongly-typed ActivityCollection class, which was basically a Hashtable with a strongly-typed String key and a strongly-typed Activity value. At that point, whenever I needed to log an impression or click, it was just a matter of adding a new item to this collection (if I didn’t already have one) or incrementing the existing item’s counter.

Incidentally, I’m not going to list the code for the collection, but I will tell you that I created it automatically using a built-in CodeSmith template (CodeSmith is free, so if you don’t have it already, get with the program and go download it now).

However, since this is meant to perform properly in a high-volume, multi-user environment, I had to consider multi-threaded access. Specifically, I had to implement a locking system that ensured that two requests did not try to increment the exact same item at the same time (a simple example of what happens without locking can be found here).

Now, we could take the naïve approach and simply lock the entire collection, but I know, I just know, that that will result in contention for that resource. (I could do yet another test to show it, but at some point I have to actually implement this code and finish this article.) I figured there had to be a way to do ‘row level’ locking of a Hashtable, and Google quickly spit one out.

Thanks to Ambrose Little and Brian Button for the final locking code shown in Figure 4. For more on how to implement locks check out the MSDN documentation: C# Spec: The lock statement.

Figure 4: LogActivity - Showing Smart Hashtable locking

private static void LogActivity(int featuredItemId, ActivityType activityType)

{

string index = featuredItemId + "-" + DateTime.Today.ToShortDateString();

AspAlliance.Framework.Common.FeaturedItemActivity item = activityCollection[index];

if(item==null)

{

// only if it is not there do we lock, and then only the

// syncroot, so that other threads can still access the Hashtable

// to read/update other items. Doing this will only block

// threads wanting to add new items to the collection

lock(activityCollection.SyncRoot)

{

// once we get our lock, check again to ensure another thread

// didn't get here first and add it while we were blocking

item=activityCollection[index];

if(item==null)

{

// still null, so we're definitely the first to try

// to add it; create the item and add it.

item = new AspAlliance.Framework.Common.FeaturedItemActivity(featuredItemId, DateTime.Today, 0, 0);

activityCollection.Add(index, item);

}

}

}

// now we can just lock the item and do our update

// with only item-level locking.

switch(activityType)

{

case ActivityType.Click :

lock (item) item.Clicks++;

break;

case ActivityType.Impression :

lock (item) item.Impressions++;

break;

}

}Now that we have a reliable way to store the data on the web server in a high-performing manner, the second step is to figure out a way to write the data to the database.

Persisting Update Data to the Database

At some point, data from the in-memory cache has to be written to the database. Typically, this is done periodically using a fixed time interval, but it could also be triggered manually or by other events, such as whenever a counter reaches a certain threshold. The greater the time between updates, the more expensive the update operation will be and the more risk of data loss is incurred. Thus, it is probably best to perform the updates regularly using a relatively short interval. For my tests, I used an interval of 5 seconds.

Actually performing the writes can be done in any number of ways. I only implemented one technique for my scenario, but the others are worth noting and may offer advantages in your situation.

A. Pure ADO.NET – loop through and call appropriate stored procedures (or parameterized SQL statements) to perform updates.

B. ADO.NET DataTable/Set – build a DataTable from the DB Schema, load it with data, and re-synchronize. (The in-memory cache could even use a DataTable instead of a Hashtable if this approach is used.)

C. Munge all of the data into a comma-delimited string and pass it to a custom stored procedure that will parse the string and perform all of the necessary inserts and updates.

D. Serialize all of the data into an XML document and pass it to a stored procedure that will then parse the XML into a table structure using sp_xml_preparedocument.

I’m sure there are other options as well, but these were the ones I considered. I know that options A and B both require at least one database round trip per data item, so I avoided them immediately. Option C seems like a bit of a hack, although I know its performance can easily exceed that of XML. It results in only one database round trip per batch update, but requires writing (or more likely, finding via Google) some custom string parsing SQL. Option D eliminates the need for any custom code, requires only a single round trip to the database, and uses standard XML rather than some custom string format. Although it might be a little slower, I’ve heard of this XML thingy, and I think it might catch on, so I went with option D.

One consideration for the technique I’m using is the possibility that some data may be lost. Storing the counters in memory means that a machine reboot or application reset or update will cause the cached data to be lost. In my scenario, this is acceptable to me, since my cache interval is only 5 seconds, and application resets are a rare occurrence.

Serializing the Collection Data to XML

I haven’t yet gotten to the stored procedure side of things, but I know that I’m going to end up passing it a big string filled with XML-formatted data. So, I need an XML schema and a way to convert my data into this XML format. Figure 5 shows an example of the XML schema that I came up with (heavily borrowed from friend Keith Barrows):

Figure 5: Sample XML Sent to Stored Procedure

<ROOT>

<Activity id='234' date='12/12/2005' impressions='23344' clicks='2344' />

<Activity id='1' date='12/13/2005' impressions='2356' clicks='53' />

</ROOT>To produce the XML, I simply overrode the ToString method (since I wasn’t using it for anything else) on my Activity class to return the contents of the class formatted as an <Activity /> element. Another option would have been to use XML Serialization for the Activity class. I opted to go the ToString route because it was simpler and, I believe, better performing. Then, in the ActivityCollection class, I overrode ToString once more, to include all members of the collection as strings, wrapped with <ROOT> and </ROOT>. Figure 6 shows the code for Activity, and Figure 7 shows ActivityCollection.

Figure 6: Serializing Individual Activity Items to XML

public override string ToString()

{

System.Text.StringBuilder sb = new System.Text.StringBuilder(100);

sb.Append("<Activity id='");

sb.Append(this.id.ToString());

sb.Append("' date='");

sb.Append(this.activityDate.ToShortDateString());

sb.Append("' impressions='");

sb.Append(this.impressions.ToString());

sb.Append("' clicks='");

sb.Append(this.clicks.ToString());

sb.Append("' />");

return sb.ToString();

}Figure 7: Serializing the ActivityCollection to XML

public override string ToString()

{

System.Text.StringBuilder sb = new System.Text.StringBuilder(this.Count * 100);

sb.Append("<ROOT>\n");

foreach(FeaturedItemActivity item in this.Values)

{

sb.Append(item.ToString());

}

sb.Append("\n</ROOT>");

return sb.ToString();

}Note that both of these methods use StringBuilder classes, rather than string concatenation. In the case of Activity, string concatenation would work about as quickly as using StringBuilder (I tested it). Feel free to go either way. However, ActivityCollection really should use the StringBuilder class for its ToString method, since there is a potentially large (and certainly unknown) number of concatenations to be made. That could easily hurt performance. (For more on StringBuilder vs. String concatenation, see Improving String Handling Performance in .NET Framework Applications.)

All that remains is to write a stored procedure that will take this XML string, parse it, and INSERT or UPDATE the contents as required. Figure 8 shows just such a procedure. It uses the sp_xml_preparedocument and sp_xml_removedocument procedures to parse the XML string into a table structure (using OPENXML). The data can then be used essentially as a table. By doing the UPDATE first for keys that are in the existing table and then doing an INSERT for keys that are not in the existing table, we ensure that we do not perform any double UPDATE or INSERT operations. One possible optimization would be to place the contents of the XML document into a temporary table to avoid the cost of calling OPENXML twice. However, I haven’t researched this enough to know if it would make much of a difference (feel free to comment).

Figure 8: Using sp_xml_preparedocument To Create a Bulk Insert Stored Procedure

CREATE PROCEDURE ads_FeaturedItemActivity_BulkInsert

@@doc text -- XML Doc...

AS

DECLARE @idoc int

-- Create an internal representation (virtual table) of the XML document...

EXEC sp_xml_preparedocument @idoc OUTPUT, @@doc

-- Perform UPDATES

UPDATE ads_FeaturedItemActivity

SET ads_FeaturedItemActivity.impressions = ads_FeaturedItemActivity.impressions + ox2.impressions,

ads_FeaturedItemActivity.clicks = ads_FeaturedItemActivity.clicks + ox2.clicks

FROM OPENXML (@idoc, '/ROOT/Activity',1)

WITH ( [id] int

, [date] datetime

, impressions int

, clicks int

) ox2

WHERE ads_FeaturedItemActivity.FeaturedItemId = [id]

AND ads_FeaturedItemActivity.ActivityDate = [date]

-- Perform INSERTS

INSERT INTO ads_FeaturedItemActivity

( FeaturedItemId

, ActivityDate

, Impressions

, Clicks

)

SELECT [id]

, [date]

, impressions

, clicks

FROM OPENXML (@idoc, '/ROOT/Activity',1)

WITH ( [id] int

, [date] datetime

, impressions int

, clicks int

) ox

WHERE NOT EXISTS

(SELECT [id] FROM ads_FeaturedItemActivity

WHERE FeaturedItemId = [id] AND ActivityDate = [date])

-- Remove the 'virtual table' now...

EXEC sp_xml_removedocument @idoc

GOYou can see another example of this technique here: SQLXML.org – How to Insert and Update with OpenXML. Now that we have a way to create the XML and consume it, we just have to figure out how to send the updates to the database asynchronously, rather than on every request.

Scheduling Asynchronous, Periodic Updates

The System.Threading.Timer class provides the functionality we need to periodically perform our write operation. Essentially what we want to do is create a timer when the logging begins and specify a period of time and a method to call using a delegate, or callback, called TimerCallback. The period determines how often the method will be called.

For my implementation, I’m using a static class, which is simply a class with no instance fields and a private constructor (so it cannot be instantiated). I’ve specified a static constructor, which is the ideal place to initiate the timer and set other configuration settings. Another option would be to use a Singleton pattern, and place the startup code in the class’s default constructor.

Figure 9 shows my static constructor. There are a few configuration items that determine whether or not batch updates are enabled and, if so, how frequently they are performed. The last two lines create the timer that links to the Persist method. Figure 10 shows this method, which extracts the XML from the ActivityCollection, clears it, and sends it to the stored procedure (Figure 8) by way of a data access layer method (not shown).

Figure 9: ActivityLogger Static Constructor

static ActivityLogger()

{

activityCollection = new FeaturedItemActivityCollection(100);

int persistDataPeriod = 10;

if(ConfigurationSettings.AppSettings["FeaturedItemPersistPeriodSeconds"] != null)

{

persistDataPeriod = int.Parse(ConfigurationSettings.AppSettings["FeaturedItemPersistPeriodSeconds"]);

}

if(ConfigurationSettings.AppSettings["EnableBatchUpdates"] != null)

{

EnableBatchUpdates = bool.Parse(ConfigurationSettings.AppSettings["EnableBatchUpdates"]);

}

if(EnableBatchUpdates)

{

TimerCallback callback = new TimerCallback(Persist);

timer = new Timer(callback, null, new TimeSpan(0,0,0,persistDataPeriod), new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0, persistDataPeriod));

}

}Figure 10: Persist Method - Responsible for Performing Batch Update

private static void Persist(object state)

{

if(activityCollection.Count > 0)

{

string xmlData = "";

lock(activityCollection)

{

xmlData = activityCollection.ToString();

activityCollection.Clear();

}

// persist impressions

AspAlliance.Data.FeaturedItem.BulkInsert(xmlData);

}

}Test - Cache Reads and Writes

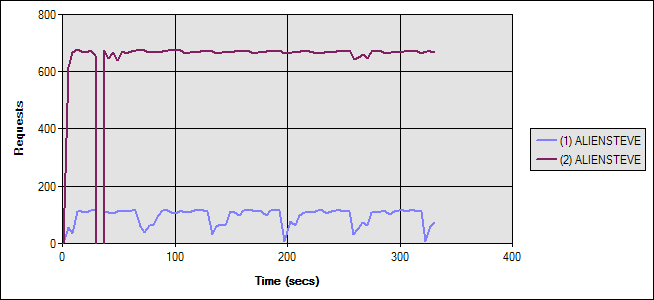

For the final test, both reads and writes will be cached to optimize performance. Naturally, this will have the best performance of the three scenarios we’ve examined (no caching, read caching, read-write caching). For this test, I enabled batch updates (write caching) in addition to the read caching enabled in the previous test scenario. I set both caching periods to 10 seconds and ran the test on two system configurations just as before (remote database, local database). Figure 11 shows a graph of the results. The blue line (1) indicates the setup with the remote database.

Figure 11 - Test Results With Read and Write Caching Enabled Test Run Graph

As you can see, the difference between the two configurations is almost zero, and the total requests per second is significantly higher for both configurations (though obviously much more so for the remote database option).

Note: The remote configuration option tended to have regular drops in requests per second in every scenario tested (but most noticeable in this last graph). I’m not sure what the cause of this is, but since the behavior was consistent across all of my tests and only lasted a few seconds, I concluded that whatever was causing it was not related to my caching, nor would it have a significant effect on my statistics. I couldn’t tie it to garbage collection or the connection pool running low, based on the performance counters I collected.

More Details

Test 1 (Blue) averaged 113.1 ASP.NET requests/second. Test 2 averaged 118.52 ASP.NET requests/second. For Test 1, the web server’s CPU averaged 69.62%. For test 2, the web server CPU (and also the db server) averaged 72.9%. Average Time to Last Byte (TTLB) in Test 1 for each whole page was 3.95ms. For Test 2, it was just 3.52ms.

Looking at the database, in Test 1, the remote database averaged 1.24 Batch Requests/sec. In Test 2, the local database averaged 0.6 Batch Requests/sec. I’m not sure why there is such a discrepancy here, but they’re both much lower than in the previous tests.

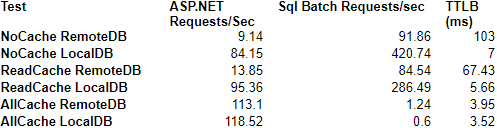

Summary

Hopefully, I’ve convinced you that write caching or batch updating can be a huge performance win for applications that must perform very frequent updates to a database, such as in a logging scenario. Figure 12 (the last figure, I promise!) shows a summary of the 6 scenarios and how the various metrics compare.

Figure 12: The Last Figure (with summary data from all tests)

In the course of finishing this article, I’ve become more and more interested in the MSMQ alternative. Hopefully at some point I’ll have time to investigate it, and probably write a follow-up article (or at least blog about it). However, for now, these results speak for themselves.

Resources

The following resources were used in developing this article:

SQLXML.org - How to Insert and Update with OpenXML

AspAlliance.com - ASP.NET Micro Caching: Benefits of a One-Second Cache

MSDN - Best Practices Using ASP.NET Caching

MSDN - Creating a Cache Configuration Object for ASP.NET

Brian Button - Simple Solution to Hashtables and Thread Safety

ASP.NET Performance Discussion List

Cooking with ADO.NET (ADO.NET and MSMQ)

Are StringBuilders Always Faster Than Concatenation?

XML Serialization in the .NET Framework

Resolving blocking problems caused by lock escalation in SQL Server

I apologize, but there is no download available for this article – the code is too tightly integrated into a live system I’m deploying. I’ve highlighted all of the key concepts and provided source code for all of the interesting parts of the problem, which I hope will be helpful enough for most readers.

Originally published on ASPAlliance.com.

Tags - Browse all tags

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.