Working Effectively with GitHub Issues

Date Published: 22 June 2022

GitHub Issues offer a simpler approach to work item management than many other systems like Jira or Azure DevOps. Despite being lightweight, it can and is used to effectively track and prioritize work on thousands of projects of all sizes.

Everything is an Issue

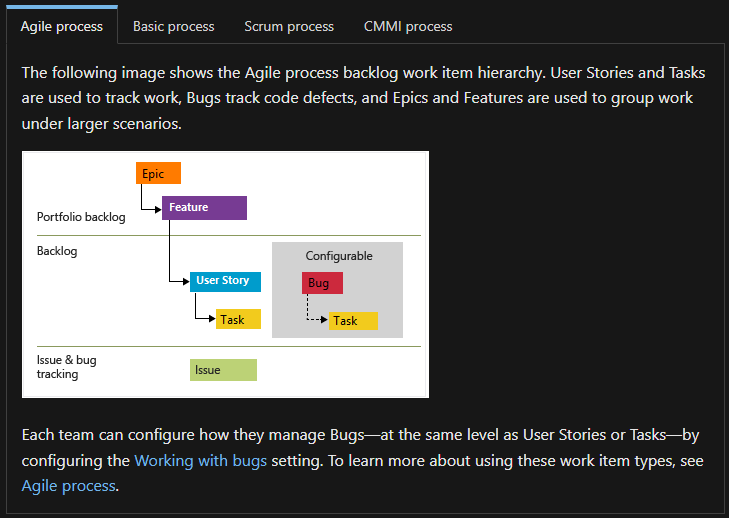

In GitHub, every work item is an Issue. Issues can be decorated with tags that indicate whether a particular Issue is a Bug, Question, Feature Request, etc. but at the end of the day they're still an Issue with an incrementing ID per repository. Other systems like Azure DevOps define a variety of work item types that form a hierarchy - GitHub Issues keep things simpler and allow repository maintainers to opt in to as much or as little complexity as desired.

Here's an image showing some of the different work item types defined by Azure DevOps, which are tied to the named process you chose when you created the project (and I believe is pretty much locked in at project creation):

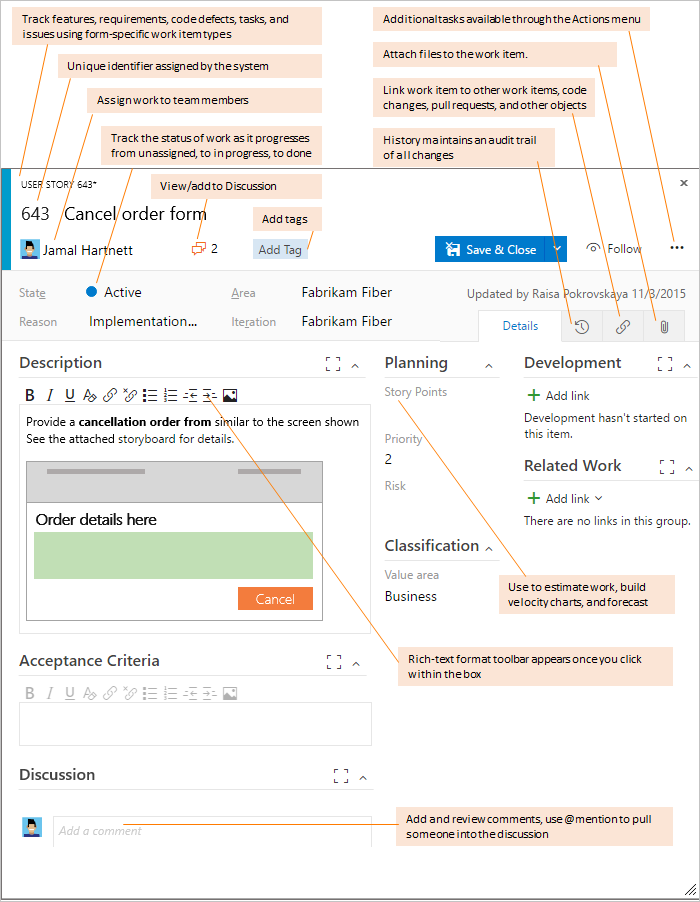

Once you have this taxonomy of work item types, creating them uses a form like this one:

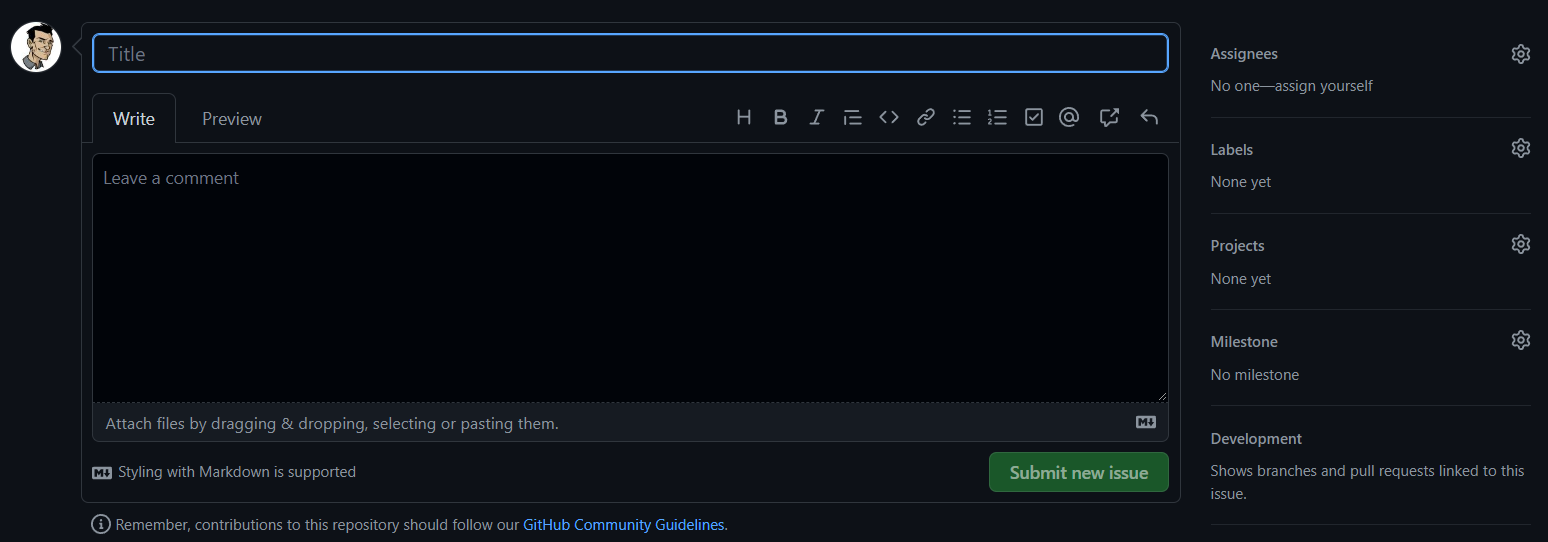

Contrast this to GitHub Issues, which have a form like this one:

The meat of the issue - its name and description (which easily supports markdown-formatted text and copy-pasted media) occupies the bulk of the interface, with any additional metadata available in menus on the side. Obviously the GitHub interface is simpler, making it easier for community members to work with open source projects, GitHub's original audience. But this simplicity also makes it easier for stakeholders on private commercial projects to work with the system, too.

Notice too that an issue is just a name and a stream of comments. Even the initial description of the issue is just a comment - the first in the stream. Every issue is just title and a discussion, which can always be edited in the future to clean things up if needed.

Team Features

One of the nicest features of GitHub's issues is the ability to mention team members (or anyone, really) by simply adding their username with '@' prefix. This makes it really convenient to pull in someone who may be interested in a particular discussion or decision. Most other work tracking systems have since emulated this feature, so it's certainly not exclusive to GitHub. But GitHub was one of the early adopters of this approach, and have integrated it everywhere in their designs.

Additionally, you can assign zero to many people to an issue. Many work tracking systems don't allow the assignment of multiple people to work items, which creates a disincentive to collaboration and pair/peer/mob programming. GitHub lets you easily assign up to 10 people to to an issue (which is more than I've ever needed).

Scoping Work

"But wait, what if we have epics, features, milestones, and tiny little tasks that we want to track? How can we treat all of these as issues and not be buried by them?"

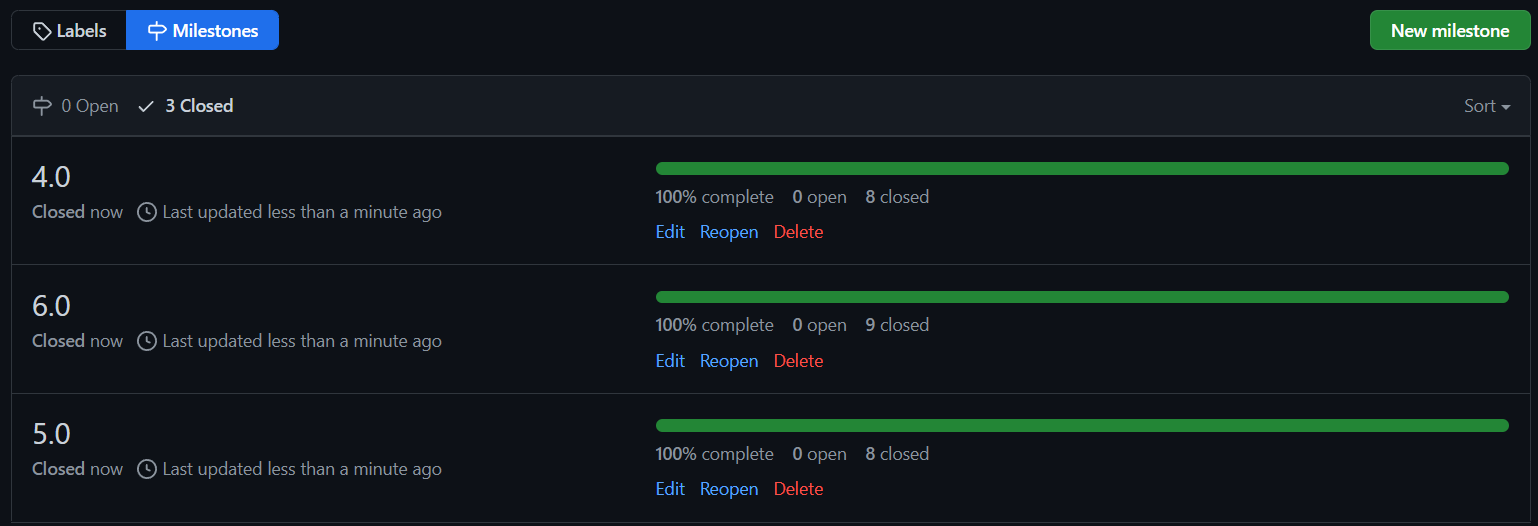

GitHub has support for Projects and Milestones, which provide easy ways to group work into buckets for coarse prioritization and management. Milestones can be given a date and will show a progress bar toward their completion based on the statuses of all of the issues associated with the milestone. Most epic/feature/milestone level buckets can easily be tracked using GitHub Milestones.

Smaller items can be tracked as part of an issue using checklists, like this:

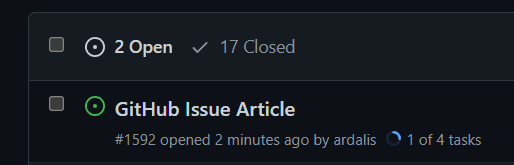

Checklist tasks are also shown in Issue Lists so you can see how things are progressing:

Of course, sometimes something that started out as a simple task becomes more complicated and deserves to be an issue in its own right, allowing you to assign it and track it separately. No problem, any checklist item can easily be converted to an issue by hovering over it and clicking the icon to the right:

Closing the linked issue completes the task in the checklist:

It's worth mentioning that you can mention issues (and pull requests, which are just a special kind of issue) anywhere by adding their id prefixed with '#'. Doing so will also add a link to the issue being referenced, showing that it was referenced and linking to the referencing item.

Filtering Issues

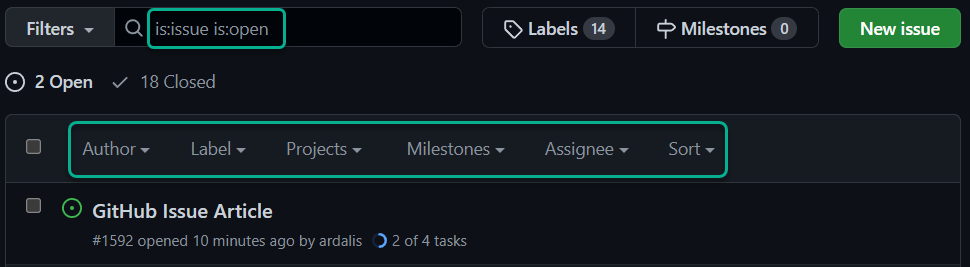

Ok, so GitHub issues work as work items and tasks, and you can bucketize them using Milestones and Projects (which I'm not getting into here). But how do you deal with large numbers of them? That's where filters come into play. You can easily filter issues based on author, labels, assignees, projects, milestones, status, and more. The default issue list includes most of these options, all of which can be applied as text options in the filter search box:

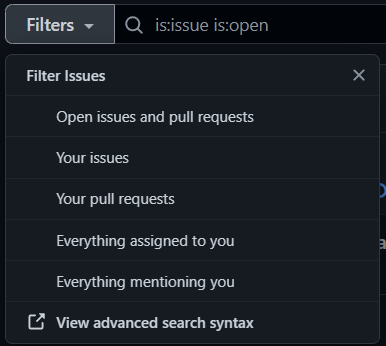

The Filters dropdown includes some common filters as well as a link to see more advanced search syntax:

GitHub has many, many options for additional and more advanced filters. You can apply these options in any combination and save the resulting query as a bookmarked/favorite URL for future use. You can add common views you need to your project's README file so they're always just a click away when you open the project.

How to deal with long conversations

One question I've heard from folks is, how to deal with long conversations in GitHub issues. For instance, an issue might have vague initial scope, but a lengthy conversation has clarified it. However, now the assignee would need to read the entire lengthy conversation to figure out what to do, and may be confused or put off by having to do this.

There are a few options to deal with this.

One, do nothing. Let whomever is going to implement the issue read through the whole conversation so they understand all of the considerations and nuance involved. They can ask any clarifying questions there themselves as they get ready to do the work. This is the default approach, but the question obviously implies that some don't think it's the ideal one.

Two, edit the original comment/description of the issue. If you are the issue's author, you can always edit the initial description to flesh it out further, clarify it, add specific tasks, etc. Doing so may make some of the comment history confusing, since you're changing the initial thing those comments were referencing, but aside from that possibility this tends to work fine.

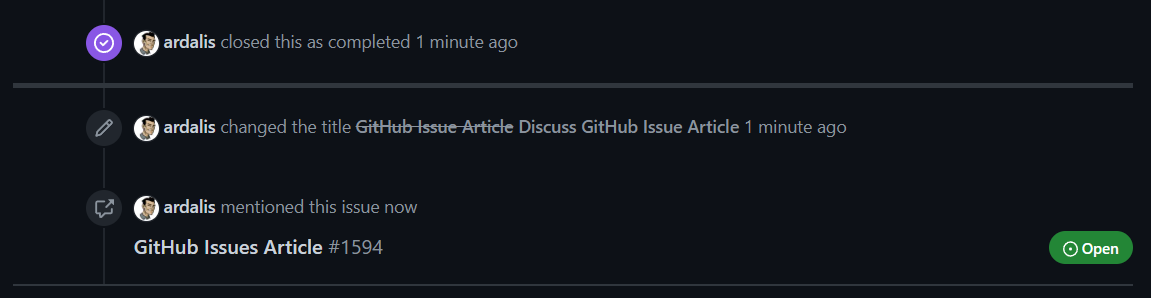

Three, create a new issue. Issues are cheap. Feel free to create new ones if the ones you have aren't working for whatever reason. You can rename the original issue "Discuss X" instead of just "X". Then close it and create a new issue called "X" which summarizes the discussion and includes the agreed-upon plan of attack for the item in question. The new issue can reference the original discussion, if desired, so anyone interested can always refer back to it. Doing so will also add a link to the new issue in the original one, like this:

GitHub Issue Templates

If you want to add more structure to your GitHub issues, you can leverage issue templates. Templates are commonly used to capture specific details for different kinds of issues, like bug reports or feature requests.

You can see an example of how choosing a template is presented as part of creating an issue in the repo for my blog.

Learn more about setting up Issue Templates for your GitHub repository in GitHub's docs.

Summary

GitHub Issues offer a much simpler and lighter-weight approach to tracking work than many other systems like Azure DevOps or Jira. Instead of having to deal with a much more complicated user interface and many more decisions, by default a GitHub issue requires only a title - you don't even need to specify a description. But from this simple beginning, GitHub provides a lot of functionality that lets you opt in to more organization, letting Issues support everything from the tiniest single-person repo to huge projects involving hundreds of collaborators from multiple companies.

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.