What are Abstractions in Software Development

Date Published: 05 January 2022

Software developers deal with abstractions every day. But just what is an abstraction? There are differing definitions that can sometimes cause confusion. Let's consider a few of them.

Definitions

Oxford (via Google as the default/top definition) defines abstraction:

ab·strac·tion /abˈstrakSH(ə)n/

noun

- the quality of dealing with ideas rather than events.

"topics will vary in degrees of abstraction" 2. freedom from representational qualities in art. "geometric abstraction has been a mainstay in her work"

These are only applicable to software development with a bit of extra thought. Software abstractions are more about ideas and generalities than specific things. And while not necessarily art in the traditional sense, abstractions in software tend to be less representational of specific real world constructs. There's something here, but these are not the most useful definitions.

Wikipedia defines abstraction:

- The process of removing physical, spatial, or temporal details or attributes in the study of objects or systems to focus attention on details of greater importance; it is similar in nature to the process of generalization;

- the creation of abstract concept-objects by mirroring common features or attributes of various non-abstract objects or systems of study – the result of the process of abstraction.

Abstraction, in general, is a fundamental concept in computer science and software development. The process of abstraction can also be referred to as modeling and is closely related to the concepts of theory and design. Models can also be considered types of abstractions per their generalization of aspects of reality.

Specific to software, then, abstraction is all about generalization and the process of modeling concepts in more or less specific or generalized ways. Abstraction is a process which is used to produce generalized concepts or models, but in software we often refer to individual parts of a model as abstractions as well.

When we talk about abstraction, we typically mean the process of modeling by generalizing and focusing on important (in a given context) details while paring away less important details. When we talk about an abstraction or abstractions we are referring to artifacts produced by the modeling or abstraction process.

The rest of this article will look specifically at these artifacts, where again further sub-categories and definitions exist (but are frequently used interchangeably).

Abstractions in C# and .NET

Many programming languages like C# define abstraction as part of their type system. The .NET Framework design guidelines have some useful guidance for properly using abstractions (abstract types and interfaces) which includes a very simple definition:

An abstraction is a type that describes a contract but does not provide a full implementation of the contract. Abstractions are usually implemented as abstract classes or interfaces...

The alternative to an abstraction in C# is a concrete type. It's possible to examine any type in C# and determine, based on whether it can be directly instantiated, whether that type is abstract or concrete. It's not unusual for .NET developers to refer to abstract types as abstractions (and occasionally to concrete types as "concretions").

Below are a few simple examples in C#:

// abstract type

public interface ILogger

{

void Log(string message);

}

// another abstract type

public abstract class BaseLogger : ILogger

{

public abstract void Log(string message);

}

// concrete type

public class ConsoleLogger : BaseLogger

{

public override void Log(string message)

{

Console.WriteLine(message);

}

}Using the definitions we've considered thus far, it's clear that ILogger and BaseLogger are both abstractions, while ConsoleLogger is a concrete implementation (or "concretion").

Qualities of Abstractions

Some abstractions are more useful than others. Remember from our earlier definition, the process of abstraction is the process of modeling. With that in mind, it's worth remembering this quote from statistician George Box:

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

We can look at a type in C# and determine whether or not it is abstract but it still may not be a terribly useful (or "good") abstraction. Good abstractions have certain properties, many of which are described by the SOLID Principles.

Good Abstractions do not Depend on Details

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) says "Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions."

We can usually look at an abstraction in isolation and determine whether it follows this principle or not. Consider the two abstractions:

public interface IOrderDataAccessA

{

SqlDataReader ListOrders();

}

public interface IOrderDataAccessB

{

FileStream ListOrders(string filename);

}By definition, these are both abstractions. You can't instantiate either type; the .NET Framework considers these to be abstract. Both types provide a model for working with data, presumably in order to retrieve order information. But they clearly do not follow DIP because they both depend on low-level details. IOrderDataAccessA depends on the SqlDataReader return type, which implies that this method will only be used to query SQL databases. And IOrderDataAccessB returns a FileStream and expects a filename argument, implying that it will only be used to read data from files.

Think about how difficult it would be to implement the first interface using files or the second interface using SQL Server. A good interface should not constrain the details of its implementation(s).

Interfaces define what needs to happen; implementations define how to do it.

We can replace both of these poor abstractions with a better one by following DIP and eliminating the dependency on low level details in the interface definition:

public interface IOrderDataAccess

{

IEnumerable<Order> ListOrders();

}Note that you could easily implement this interface using any kind of implementation (database, files, web apis, in memory, anything). This is a direct result of the fact that it follows the Dependency Inversion Principle.

Good Abstractions are Focused

Two more SOLID principles help guide us to writing better abstractions:

- Single Responsibility (SRP)

- Interface Segregation (ISP)

SRP is typically applied to classes, but remember that when a class implements an interface, it must implement all of it (if they don't, then they're breaking another SOLID principle, Liskov Substitution). Thus, abstractions that don't follow SRP will produce classes that don't follow SRP.

One way to help keep interfaces focused is to look at how they are consumed. ISP says that classes "should not depend on methods they do not use." If you have large interfaces with many methods, it's likely that some clients will only need a subset of these, and thus will break ISP.

Good Abstractions are Stable

There are several principles that guide us to the conclusion that good abstractions should be stable. Stable in this context means that they are hard to change, and as a result, rarely changed.

First let's hit on the last of the SOLID principles, the Open-Closed Principle (OCP), which states that software constructs should be open for extension, but closed for modification. Abstractions are meant to be extended through their concrete implementation(s), which have no impact on the abstraction itself. However, sometimes abstractions within a system need frequent updates to support new requirements. Every change to an abstraction impacts all of its implementations, which can have huge ripple effects in an application. Good abstractions should change rarely, if ever.

If you find your design requires updates to certain abstractions on a regular basis, look for a better design.

The Stable Dependencies Principle (SDP) states that dependencies between packages should be in the direction of the stability of the packages. That is, a package should only depend on packages that are more stable than it is.

Likewise, the Stable Abstractions Principle suggests that the most stable packages should be the most abstract. That in fact the abstractness of a package should vary in proportion to its stability.

Taken together, these principles suggest that your application's abstractions should ideally be packaged together in a package that is more stable than the consumers of it. Following these (and other) principles will lead you to build systems using something approaching Clean Architecture or some variation thereof (ports and adapters, hexagonal, onion, etc.).

It's also worth noting that these principles are not purely subjective. Things like stability and abstractness can be calculated for a given package. Instability is often defined based on dependencies or coupling, with inbound (or "afferent") coupling and outbound ("efferent") coupling compared using this equation:

I = (Ce / (Ca + Ce))

A component that has no outbound coupling (it depends on nothing) is completely stable; instability = 0. A component that depends on many other components (and perhaps has no components depending on it, such as for many app entry points) would have an instability of 1 or close to it.

Likewise the abstractness of a package can be calculated using a similar ratio of abstract to concrete classes:

A = Sum(Abstract Classes) / Sum(Abstract and Concrete Classes)

In C# you would include interfaces as well as abstract classes to get this ratio.

Tools like NDepend can quickly calculate stability and abstractness for any given .NET app, plotting the two values on a chart to see how closely abstractness and instability align. You can use these to help ensure your package design doesn't lead you to the "Zone of Uselessness" or the "Zone of Pain."

Models as Abstractions

Remember that an abstraction is a model, and modeling isn't just about types you cannot instantiate (i.e. abstract types in C# and similar languages). Your whole domain model, not just the interfaces and abstract classes, is an abstraction. Design patterns, whether they use interfaces or not, are abstractions. User interfaces are abstractions. Any API, whether concrete or not, is an abstraction. Just about everything we deal with in the course of building working software involves abstracting from real world concepts, ideas, and things into software models that represent them.

In many instances, when someone is talking about abstractions in the context of software development, they're referring to this definition of the term. The whole application, or some part of it, is an abstraction regardless of the individual types involved, because it's modeling some process.

When evaluating rules or best practices about abstractions, keep this definition in mind as well.

Confusing (or Outright False) Rules of Abstractions

There are some articles and "rules" of abstractions that, while their intentions are generally good, can lead to confusion if taken out of context (or applied as generally as their sound bite would imply). I'd like to point out a couple here and explain why I think they would be better if they were a bit more nuanced.

Interfaces are not Abstractions

Mark Seeman wrote, some time ago, that Interfaces are not Abstractions. I have a great deal of respect for Mark and I recommend his book on Dependency Injection as required reading for any .NET developer. But I take issue with this article that makes that argument that abstractions and interfaces are totally separate things that might overlap somewhat like this:

Mark goes on to discuss many ways in which an interface might not be a good abstraction, due to SOLID violations or because tools due a poor job of automatically generating interfaces from classes, etc. I agree with all of these points.

However, none of it changes the simple fact that, by every definition we've covered so far, interfaces are in fact abstractions. But some of them aren't terribly good abstractions.

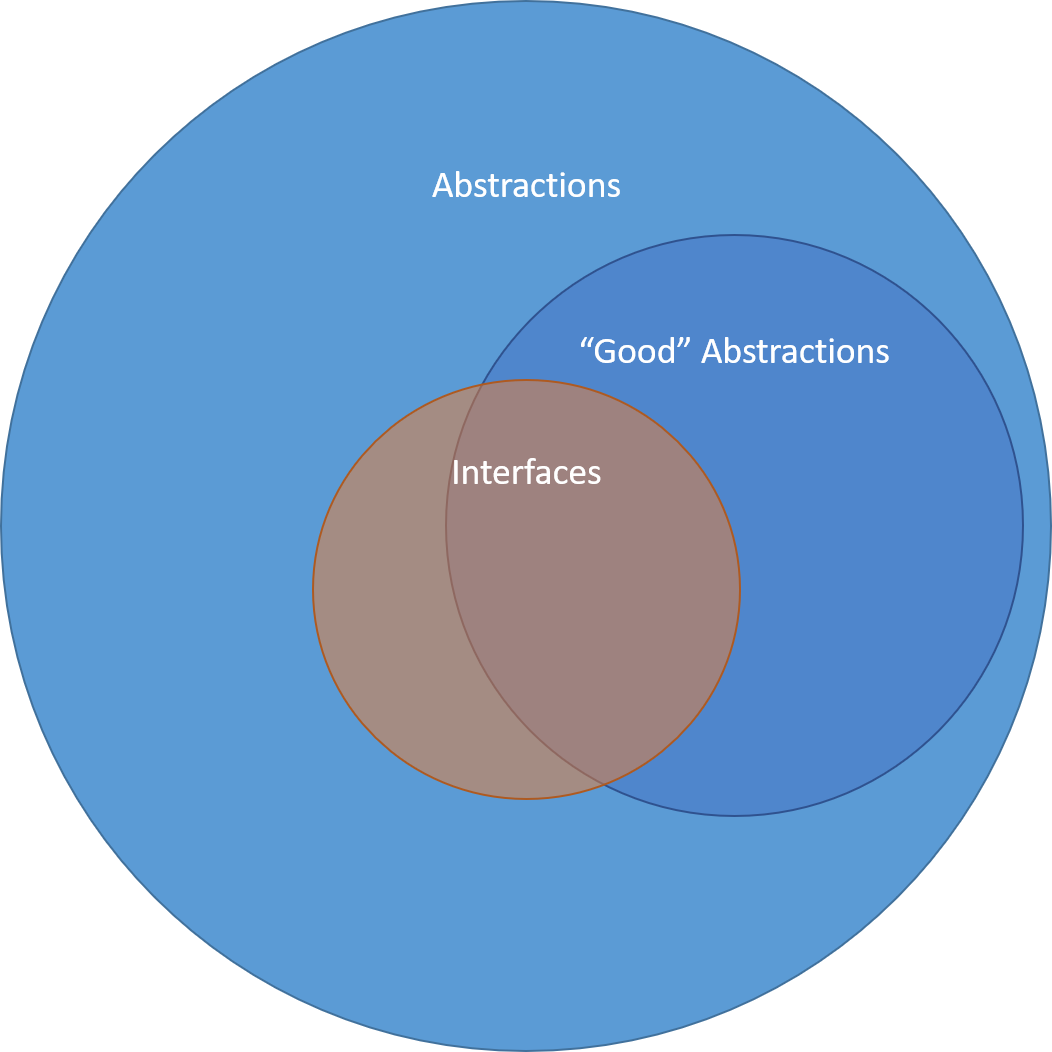

This leads to the following, more nuanced Venn diagram:

And the conclusion that the article would be improved by the addition of a couple of words:

"Interfaces are not always good abstractions"

I know, it's not as catchy...

Interfaces with a single implementation are not abstractions

Vladimir Khorikov, a fellow Pluralsight author with a lot of great content, contends the following:

Interfaces with a single implementation are not abstractions though :)

— Vladimir Khorikov (@vkhorikov) December 9, 2021

"Interfaces with a single implementation are not abstractions."

Which he elaborates on in his book on unit testing:

“Genuine abstractions are discovered, not invented” (from Unit Testing Principles, Practices, and Patterns by @vkhorikov) pic.twitter.com/QZ0ainhj63

— Mike Kowalski (@mikemybytes) November 9, 2021

You can see just in the expanded version of his position from his book that his actual position is more nuanced than the simple statement would lead you to believe. But in conversation with him, he really does want to stick to the simple version of the "rule," rather than allow for a more accurate version. He also introduces the term "genuine abstractions" which here I'll argue is a synonym for "good abstractions".

So, what's wrong with this statement, that all interfaces with exactly one implementation are not abstractions, and also, what's right about it?

First, just like the previous article about interfaces and abstractions, it goes against every definition of abstraction we've discussed. Interfaces, all interfaces, are abstractions. Period. But are they "good" or "genuine"? Maybe, maybe not. Let's amend the rule so we can keep going:

"Interfaces with a single implementation are not good abstractions."

You should typically be able to look at an interface and determine whether or not it's a good abstraction (or at least if it exhibits known problems as described above) without seeing any other code. One problem with this "rule" is that it requires knowledge of the implementations of the interface in order to make a value judgment about it. I admit this is often helpful - your interfaces should fit within the context of your system and its model - but I can't see how this pass/fail rule makes sense. Especially if you're defining your interface in one package and potentially consuming it in other packages - how can you even be sure how many implementations of it there are, total, everywhere?

Let's look at the example I showed above, that follows DIP:

public interface IOrderDataAccess

{

IEnumerable<Order> ListOrders();

}Applying this (single implementation) rule, is it a (good) abstraction?

There's no way to know, since we don't know how many classes implement it. Let's say there are 0 implementations, currently. Is it an abstraction? We know it is, because it's purely abstract. This rule only says that interfaces with exactly one implementation are not (good) abstractions; it's silent about those with 0 or 2+ implementations. So it's not helpful here.

Now I add this implementation:

public class InMemoryOrderDataAccess : IOrderDataAccess

{

public IEnumerable<Order> ListOrders() { return new List<Order>(); }

}Boom! Now we know this interface is not a (good) abstraction, because it has exactly one implementation. Success! But wait, what changed about the interface? If it was a (good) abstraction before, why did it suddenly become a bad one now? Or if the rule is silent on 0 and 2+ implementation interfaces, is there any way to improve it so it might be more helpful? What happens when I do this?

public class InMemoryOrderDataAccess2 : IOrderDataAccess

{

public IEnumerable<Order> ListOrders() { return new List<Order>(); }

}Well, shoot. Now the rule is silent again. It's too bad it only has anything to say in exactly one case, and that somehow the changes in the interface's quantity of implementations is materially changing whether or not it's a (good) abstraction in some manner.

Hold on, what about fakes/mocks/stubs that might implement the interface? That would be a sure way to ensure it would always have at least 2 implementations: one for production use and one for tests. Nah, VK says those don't count, because, reasons.

Looking back at the context of the statement from his book:

"Genuine abstractions are discovered, not invented. The discovery, by definition, takes place post factum, when the abstraction already exists but is not clearly defined in the code."

Now I think we're back to the original definition of abstraction, which is a discovery and modeling process used to identify the important parts of an idea or process in order to build a useful model. VK is saying that frequently developers will jump to creating abstractions too quickly, rather than waiting to see how their model develops and then identifying the useful abstractions within it. It's a kind of premature optimization. I agree with this 100%.

But none of that says anything about whether interfaces are abstractions, or even good abstractions, based on their quantity of implementations.

At best we can say:

Interfaces with a single implementation in production code are a code smell, because they may be poor abstractions due to being too tightly coupled to their sole implementation.

This is a true statement. It's somewhat nuanced, but the truth often is. Code smells aren't necessarily wrong or bad, they're just worth looking a bit more deeply into because they might be a symptom of a problem in the software's design.

Perhaps an interface was created prematurely, either by hand or using a tool, that is tightly coupled to the implementation details of the sole class that does this work currently in the system. Knowing that there is a 1:1 relationship between the interface and its only implementation might help you to look into this design and see if it has any problems (like the ones described above related to SOLID, stability, etc.). In that sense, it could be a useful heuristic when evaluating code, but you'd ideally want to have a way to exclude all of the interfaces that had only one implementation but which were, in fact, good abstractions.

Overall, the rule is false on its face, and leaves out a lot of nuance. The updated, truthful rule is, sadly, not nearly as catchy. It's also much harder to fit into a tweet. But it's one I could probably stand behind. I'd still rather stick with the rules for good interfaces that I laid out above, though.

Summary

Ok, this got longer than I'd anticipated. The key takeaways are that there are multiple definitions for abstraction and even abstractions. Some ideas can be evaluated as true/false, such as whether or not a type in C# is abstract or concrete. Others may require some subjective assessment to determine whether a given abstraction is good, genuine, useful, etc. or not. And some rules which claim to assess whether something is an abstraction or not are really just talking about whether the thing is a good abstraction (or not).

If you'd like to discuss, please leave a comment below or post on twitter and be sure to mention @ardalis and this article.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.