Real World Monitoring and Tuning ASP.NET Caching Part 2

Date Published: 21 September 2010

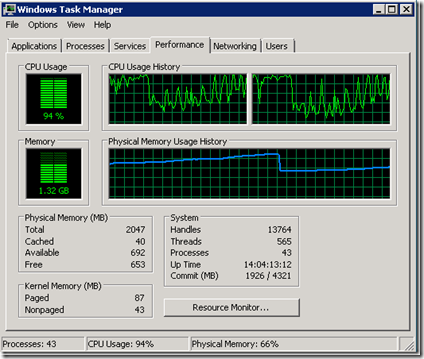

In Real World Monitoring and Tuning ASP.NET Caching Part 1, I showed the behavior of a certain ASP.NET application under load. We resolved the issue today, which turned out to be a result of two related issues that, thankfully in our case, were limited to a single class in our application that was responsible for interacting with our cache. Here’s the old behavior:

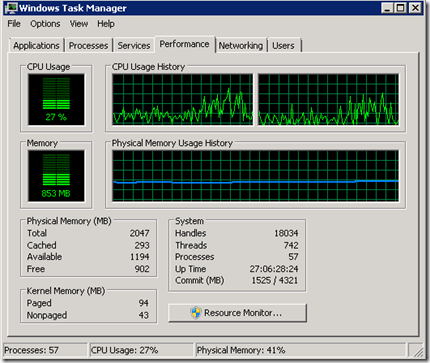

The new version of the same application, under pretty much the same load, looks like this:

Note the lack of ever-growing memory followed by high-CPU utilization as the memory is reclaimed. In my last post, I suggested that there were several approaches we could take to correct the issue, one of them being to throw hardware at it. We tried that, in fact, and added an 8-core 8GB server to the NLB for the application. Unfortunately, it had the same characteristic climbing RAM and huge drop as the lightweight server shown here, with the added *bonus* that when it was reclaiming its RAM, it was unresponsive for several times longer (over a minute). Not acceptable.

Using a variety of memory profiler tools, including the ones built into VS2010, we determined that a very large number of CacheDependency objects were being created by the application, so we started looking there. A potentially related issue we’d noticed (I’d seen for years, actually) with the application was that sometimes, on a cold start under load, it would take a long time to start responding, and it would log errors stating that it was unable to talk to the SqlCacheDependency database (these would be timeout errors). The stack trace looked like this:

System.Web.HttpException (0x80004005): Unable to connect to SQL database ‘MyDatabase’ for cache dependency polling. at System.Web.Caching.SqlCacheDependencyManager.EnsureTableIsRegisteredAndPolled(String database, String table) at System.Web.Caching.SqlCacheDependency.GetDependKey(String database, String tableName)

If you’re seeing these kinds of errors, but only on app startup, then you probably have a similar issue to ours. Keep reading.

The Cache Access Pattern

I’ve written before about the ideal cache access pattern. Some things have changed with .NET over the years, making it much easier to use delegates via lambdas, so the pattern has evolved a bit. Here’s what the pattern we were using before today looked like, encapsulated into a single class implementing an ICacher interface.

// Problem Code - Don't Use

private TObjectToCache GetCachedObject<TObjectToCache>(string cacheKey,

Func<TObjectToCache> getObjectToCache,

CacheDependency cacheDependency,

DateTime absoluteExpiration) where TObjectToCache : class

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(cacheKey))

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("cacheKey",

"Given cache key cannot be null or empty.");

}

if (getObjectToCache == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("getObjectToCache");

}

var cachedObject = _cache[cacheKey] as TObjectToCache;

if (cachedObject == null)

{

cachedObject = getObjectToCache();

InsertIntoCache(cacheKey, cachedObject,

cacheDependency, absoluteExpiration);

}

return cachedObject;

}So, this is pretty decent code. It would run almost any ASP.NET site just fine. But it has a very real problem, which presents under load. Can you see it? Scroll down for the solution.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Hint: Here’s an example of how this would be called:

{

DependencyFactory.CreateSqlCacheDependency(PublisherTableDependency),

};

var cacheDependency =

DependencyFactory.GetAggregateDependency(cacheDependencies);

return _cacher.Cache(cacheKey,

() =]

public override IEnumerable<Publisher> GetTop20RankedPublishers()

{

const string cacheKey = "GetTop20RankedPublishers()";

var cacheDependencies = new[]

{

DependencyFactory.CreateSqlCacheDependency(PublisherTableDependency),

};

var cacheDependency =

DependencyFactory.GetAggregateDependency(cacheDependencies);

return _cacher.Cache(cacheKey,

() => BaseGetTop20RankedPublishers(),

cacheDependency);

}.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Issue 1 – Locking

A known issue with the pattern shown is that it doesn’t include any locking. This, in most sites, is not much of an issue, because the number of requests that might come into the method looking for the data is usually in the single digits, and if a couple of requests both hit the data source and add the result to the cache, it’s not a big deal. However, for our application the load is quite high, and there are a lot of methods like this one, so when the application restarts, there are dozens and dozens of requests entering this method. The result is a lot more database queries than are required. WAY more than are required, as Issue 2 will show.

To change the original code so that it includes locking, you would modify it to impose a lock around the fetching of the item from the source. A TimedLock is ideal for this, since you probably don’t want to use the default language lock semantics, but would prefer to have things fail fast, and let blocked requests have a chance at completing. IanG has a nice TimedLock implementation, and his post links to some additional mods from Phil Haack. Using this code, you might arrive at something like this:

var cachedObject = _cache[cacheKey] <span style="color: #0000ff;">as</span> TObjectToCache;

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> (cachedObject == <span style="color: #0000ff;">null</span>)

{

<span style="color: #0000ff;">using</span> (TimedLock.Lock(CacheLock<TObjectToCache>.GetLock(), Timeout))

{

cachedObject = _cache[cacheKey] <span style="color: #0000ff;">as</span> TObjectToCache;

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> (cachedObject == <span style="color: #0000ff;">null</span>)

{

cachedObject = getObjectToCache();

InsertIntoCache(cacheKey, cachedObject, cacheDependency, absoluteExpiration);

}

}

}Timeout is an int property on the Cacher class, set to 5 (seconds) by default. One reason why I hadn’t ever bothered to add locking to this code in the past was that I didn’t want to block additional requests for unknown periods of time, but the TimedLock is beautiful in that it lets you easily configure how long you’re willing for the lock to last. the CacheLock

<span style="color: #0000ff;">public</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">class</span> CacheLock<CachedObjectType>

{

<span style="color: #0000ff;">private</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">static</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">object</span> objectLock = <span style="color: #0000ff;">new</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">object</span>();

<span style="color: #0000ff;">public</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">static</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">object</span> GetLock() { <span style="color: #0000ff;">return</span> objectLock; }

}With locks in place, that cuts down significantly on how many requests can be asking the database for results at the same time. A few unit tests confirmed that the locks work (remember you can reset the Timeout in your unit tests if you’re smart; keep your unit tests running as quickly as possible).

There’s another, more subtle problem with the original code. It’s apparent in the calling code.

.

.

.

.

.

Issue 2 – Premature Instantiation of SQL Cache Dependencies

The ICacher interface has a few different methods, but the ones that can handle cache dependencies take them in directly as parameters. So, the pattern for calling the code is something like:

<span style="color: #008000;">// define cache key</span>

<span style="color: #008000;">// new up dependencies</span>

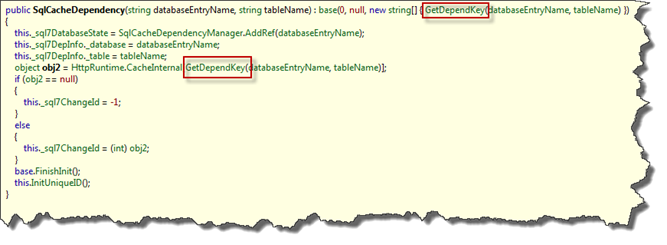

<span style="color: #008000;">// call _cacher.Cache(key,()=> GetData, dependencies)</span>The problem with this is thatcache dependencies, and in particular SQL Cache Dependencies, do work when they are instantiated. Here’s a look at the constructor for a SqlCacheDependency, using the polling style (from Reflector):

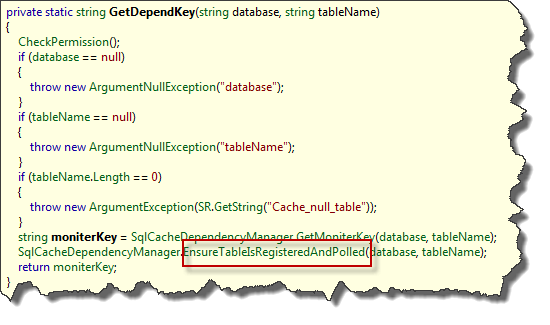

Here’s the GetDependKey() method:

The EnsureTableIsRegisteredAndPolled() method will actually call your database to see if the table is listed in its aptly named AspNet_SqlCacheTablesForChangeNotification table. It implements its own locking code and caches the result, so this isn’t something needs to happen on every request, but it is an issue with a heavily loaded application on startup, because tons and tons of these things might be firing off (from different code paths) at the same time, resulting in no connections left in the connection pool or otherwise Denial-Of-Servicing itself from the database.

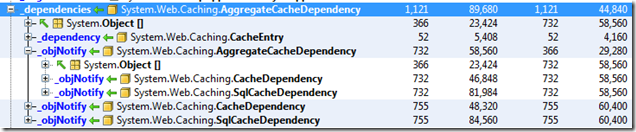

The other issue here is that every one of these SqlCacheDependency objects is relatively expensive even if it isn’t itself hitting the database to see if the table is enabled. And for an application that is doing over 100 requests per second, with multiple database requests per request, and often several dependent tables on each sql request, the number of objects being created for no reason at all is quite large.

The solution to this is to refactor our original method so that it no longer takes a CacheDependency as a parameter. Rather, it takes a Func

<span style="color: #0000ff;">private</span> TObjectToCache GetCachedObject<TObjectToCache>(<span style="color: #0000ff;">string</span> cacheKey,

Func<TObjectToCache> getObjectToCache,

Func<CacheDependency> getCacheDependency,

DateTime absoluteExpiration)

<span style="color: #0000ff;">where</span> TObjectToCache : <span style="color: #0000ff;">class</span>

{

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> (<span style="color: #0000ff;">string</span>.IsNullOrEmpty(cacheKey))

{

<span style="color: #0000ff;">throw</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">new</span> ArgumentNullException(<span style="color: #006080;">"cacheKey"</span>,

<span style="color: #006080;">"Given cache key cannot be null or empty."</span>);

}

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> (getObjectToCache == <span style="color: #0000ff;">null</span>)

{

<span style="color: #0000ff;">throw</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">new</span> ArgumentNullException(<span style="color: #006080;">"getObjectToCache"</span>);

}

var cachedObject = _cache[cacheKey] <span style="color: #0000ff;">as</span> TObjectToCache;

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> (cachedObject == <span style="color: #0000ff;">null</span>)

{

<span style="color: #0000ff;">using</span> (TimedLock.Lock(CacheLock<TObjectToCache>.GetLock(), Timeout))

{

cachedObject = _cache[cacheKey] <span style="color: #0000ff;">as</span> TObjectToCache;

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> (cachedObject == <span style="color: #0000ff;">null</span>)

{

cachedObject = getObjectToCache();

InsertIntoCache(cacheKey,

cachedObject,

getCacheDependency == <span style="color: #0000ff;">null</span> ? <span style="color: #0000ff;">null</span> : getCacheDependency(),

absoluteExpiration);

}

}

}

<span style="color: #0000ff;">return</span> cachedObject;

}Refactoring the calling code so that it makes use of the delegate via lambda expressions is very simple:

<span style="color: #0000ff;">public</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">override</span> IEnumerable<Publisher> GetTop20RankedPublishers()

{

<span style="color: #0000ff;">const</span> <span style="color: #0000ff;">string</span> cacheKey = <span style="color: #006080;">"GetTop20RankedPublishers()"</span>;

<span style="color: #0000ff;">return</span> _cacher.Cache(cacheKey,

() => BaseGetTop20RankedPublishers(),

() => DependencyFactory.CreateSqlCacheDependency(PublisherTableDependency));

}Summary

Analyzing memory leaks can be very tricky business. The tools included with VS2010 are quite good. I also played around with JetBrains dotTrace Memory 3.5 (trial) for this, and found it easy to use and helpful as well (here’s a screenshot of dotTrace):

The two takeaways I have from this for others are:

-

Implement locking on your cache access if you find that it’s causing problems. If you don’t have pain, don’t necessarily worry about it.

-

Don’t create SqlCacheDependencies (or any CacheDependency) if you’re not going to use it. In our case this was a problem caused by our implementation of the Cacher / ICacher interface, because we chose to take in the CacheDependency as a parameter. Use delegates to get expensive objects you may or may not need, so that you can get them just-in-time and only if required.

Some things that made fixing this easy once the issue was identified:

-

Abstract your cache access. We have an ICacher interface that defines how we add things to a cache. We also, separately, have an ICache interface that wraps the actual cache implementation. We have tests of ICacher that run without any real cache instance involved, which was invaluable in testing this change and getting it done in a few hours of coding.

-

Abstract your caching from your data access. We’re using the Repository pattern heavily, along with an IOC container for wireup. We have, for instance, an IFooRepository interface, and a FooRepository implementation that knows how to fetch data from the database (usually through an ORM), but knows nothing about caching. We then use the Decorator pattern to implement caching, subclassing our FooRepository to create a CachedFooRepository. This class simply overrides each method that we want to cache, and calls its base method to fetch the actual data.

Making the changes in our code to add locking and how we add cache dependencies was almost completely done in one file, and the calls to that code simply had to change from passing an instance to passing in a lambda, like () => GetCacheDependencies() or () => { return new SqlCacheDependency(foo,bar);}. The Inline refactoring (ctrl-alt-N) proved to be very useful for this.

For more on this kind of things, you should follow me on twitter, and of course you can get tips via email or podcast.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.