PSAT Observations

Date Published: 01 October 2019

The PSAT or preliminary SAT is a test that US high school students take in their junior year. It is also known as the National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test (NMSQT). Although it is a single test, it can have huge implications for the students taking it. Depending on a student’s score, they may be selected as a National Merit Finalist. Aside from sounding cool, this title alone might allow them to receive thousands of dollars in scholarships. In fact, many state schools will offer full ride scholarships to National Merit Finalists, which is obviously a big deal, more so today than when I graduated from college since tuition costs have far outpaced inflation and average earnings.

I was a National Merit Finalist and scholarship recipient, as was my wife, so I have some personal experience with the test and its potential impact on students who meet the qualifying criteria to receive scholarships. Both of us were in the position where we had to pay for college entirely by ourselves, so having a National Merit Scholarship made a huge difference for us, in college and beyond. We’ve seen similar stories about the impact of the National Merit program on others, so we’ve generally felt pretty favorably about the program, although we never really knew much about the intricacies of how it actually worked.

Now, as a parent of a high school senior, I’m learning a lot more about the college admissions process than I ever knew when I was a student. There’s a lot more information out there, and students are under a lot more pressure, both to get into colleges and to pay for the rising costs of education. As a National Merit Finalist, I’ve observed with specific interest the process my daughter and her peers have gone through in the last 12 months with regard to the PSAT test. Unfortunately, what I’ve found has caused me to question the entire program.

The basic premise of the National Merit program is that the results of a single test can serve as an accurate assessment of a student’s potential. Disregarding the obvious shortsightedness of that idea, it also assumes that the test will be administered under equal circumstances to all students, and it implies that the same test will be given to all students. Here is where things really start to fall apart. “The test” is actually NOT a single test, but rather multiple tests, given on multiple dates. Those tests are then curved relative to each other so that the “correct” number of students receive certain scores. And those scores are then broken down by state, so that ultimately the “right” number of students in each state are recognized as National Merit Finalists. All of these numbers are determined by the College Board, who, incidentally, charges students for the privilege of participating. In the end, the final results are actually based on a lot of luck (which test you take, where you live, are you having a good day), and that’s assuming that everything goes as planned.

This past year (2018), things very much did not go as planned.

The company responsible for giving the test, the College Board, released an apparently very flawed test on one of the only 2 dates on which students could take it. A detailed analysis of this issue by PhD Jed Applerouth can be found here, but essentially the College Board decided one test was particularly easier than the other, and as a result they decided to apply an excessively harsh curve to the scores based on the number of questions missed, per category. As a result, students with nearly perfect scores on one test were denied recognition, due to the random chance of taking the test on the “wrong” day.

That’s a pretty ridiculous situation, especially given that this single test can have such a profound impact on the future of individual students. So how did this happen? And what does it mean?

A Flawed Approach

The College Board employs secret algorithms to ensure that the right number of students qualify for National Merit status each year. There is some curving of the tests each year, to help correct for any difference in difficulty between test versions, but the curve of the 2018 test was particularly egregious.

According to the College Board, the 10/24/2018 test was significantly easier than the 10/10/2018 test. That means that a perfect score on the 10/24 test should be of lesser value than a perfect score on the 10/10 test. But that reality poses problems for the College Board. How would they deal with the potential issue of students getting a perfect score on their test yet still not qualifying for National Merit consideration?

It wasn’t acceptable to the College Board to correct the issue across the board. Nor was it in their financial interests to offer students the chance to retake the exam when the issue quickly came to light shortly after the tests were administered. Instead, they chose to compensate for not adjusting perfect scores by imposing heavy penalties on any questions missed in a given section — especially the first question missed. Let’s look at some examples.

Let’s say a student does very well on the overall test and misses just 3 of 139 questions (a respectable 97.8%). If these were 3 math questions missed on the 10/10 test date, they’d have a score of 1490 (out of 1520 perfect score) – essentially each missed question would be -10 off of the raw score. But if they missed those same questions on the 10/24 test date, their score would be 1400/1520 – each missed question now -40 off of the raw score. The cost of a each error on the 10/24 date is 4 times as high as on the 10/10 date. If you only miss a single math question, the difference is even starker, with a deduction of 50 points on 10/24 versus 10 on 10/10. Missing one question is 5 times worse on one test than the other.

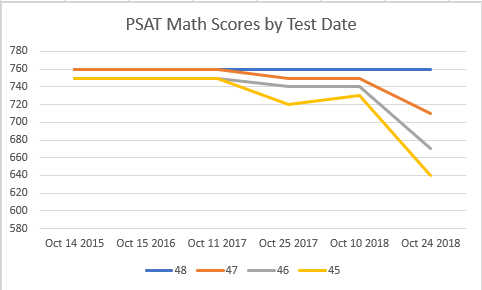

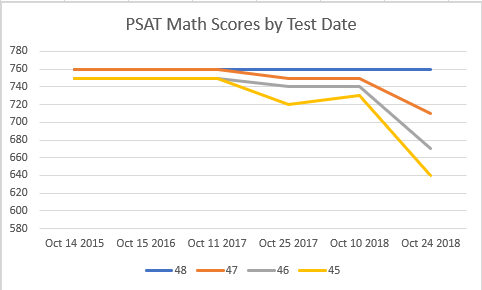

This is not a reasonable way to adjust the results, but is a symptom of the fact that the College Board refused to address curving perfect scores on the easy exam, resulting in severe adjustments to nearly-perfect scores. Is it outside the bounds of “normal” for the College Board? Have a look at the last 6 PSAT tests given and their resulting scores and see if you can spot the outlier:

Each line is raw score out of 48 questions; dates are test dates.

In 5 of the last 6 tests, missing one question had either 0 or a -10 impact on overall score. Compare that with the most recent 24 October result in which missing one question cost 50 points.

How is the test used?

The scores mentioned above are converted into a selection index scores ranging from 60-240. These selection index scores are then used on a state-by-state basis to determine who qualifies as a National Merit Semi-Finalist, which is used as a qualifier for national merit scholarships. Semi-Finalists then take the SAT and based on their SAT score they may become a National Merit Finalist and thus eligible for automatic college scholarships. The qualifying selection index varies by state, and in many cases varies quite a bit, as this old freakonomics article describes, meaning the same score might or might not qualify you for scholarships based on which side of a river or state border you live on.

The role of the PSAT as a qualifying test should not be overlooked, either. Becoming eligible for National Merit scholarships is not a result of an aggregate of one’s PSAT and SAT scores, which might make more sense. No, instead, the PSAT is a one-time, no-retakes gatekeeper. Have a bad day, but then go on to get a perfect 1600 SAT? Sorry, too bad. You missed your chance.

Or did you… ?

Your PSAT Score Can Only Hurt You

It turns out that using the PSAT as your National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test is actually optional. If you either failed to take the PSAT due to extenuating circumstances, or you did take it but felt like you didn’t do well due to illness, etc., you can write to the college board and request entry into NMSC by alternate testing. This essentially means they will use your SAT (without essay) score in place of the PSAT.

In fact, on rare occasions where entire schools have mistakenly administered the wrong PSAT test to their students, whole classes of students have been given the opportunity to use their SAT score in place of the PSAT.

So, consider these facts:

- The PSAT is a single test which, if a particular test is considered flawed in some way, can be curved to severely punish even the smallest mistakes.

- Failing to have a near-perfect PSAT will eliminate you from even having your SAT considered. In order to have your SAT considered, you must advance to National Merit Semi-Finalist. Or…

- If you write to the College Board and request alternate testing due to illness or other extenuating circumstances, provided you do so very soon after taking the PSAT (or failing to do so) and provided you have your school administration’s support, you can bypass the PSAT entirely. Essentially, one letter to the College Board can make you a National Merit Finalist for the purposes of using your SAT score for consideration. And don’t forget you can take the SAT multiple times.

I know students who missed only 3 questions on the PSAT, did not qualify for Semi-Finalist, but who scored 1560 (out of 1600) on their SAT. I sincerely doubt that a 1560 would not be high enough to qualify for a National Merit Scholarship (an SAT selection index of at least 232, depending on ERW/Math split). However, because they missed 3 questions on 10/24 (PSAT selection index: 215) rather than on 10/12 (PSAT selection index: 223), they were blocked from consideration (and at the time they didn’t know this punishing curve was a possibility or that one could contact College Board for an alternate test option). At this point their parents are considering legal action against the College Board, as they probably should given the incompetence displayed and the impact it has on the students in question.

What the College Board could have and probably should have done with the 10/24 exam is let those students who had high scores (using the same algorithm as the 10/10 exam) use alternate testing if they chose to do so. They could have included a letter with the students’ results informing them of the option to do so. This would have mitigated the damage from their error in a way that didn’t unfairly punish students for scheduling their test on the “wrong” day. There’s already precedent for doing so with entire schools, so there’s no reason this approach could not have been applied to a portion of students impacted by the 10/24 exam’s problems.

A Closer Look at the College Board

For those unfamiliar with the College Board, it bears taking a closer look at this organization. Ostensibly a non-profit, they had revenue of $1.12 Billion in 2017. Their CEO, David Coleman, had a starting salary of $1.2 million in 2013. Not bad for a non-profit. How do they make so much money, you ask? In addition to the PSAT, they also administer the SAT and the SAT subject tests. Also the Advanced Placement (AP) Tests, and the College Level Examination Program (CLEP). And, if you love the Common Core Standardized Tests, you can thank David Coleman – he helped architect those too, albeit before starting at the College Board. Oh, and if you’ve been drained of hundreds of dollars in testing fees while your student is in high school and plan to file for financial aid, don’t worry – the College Board also controls the CSS/Financial Aid profile, and they manage to charge both students and colleges a great deal of money each year for that service.

In short, despite being a non-profit, they have massive resources and compensate their leadership team lavishly. They should be held to a higher standard than they demonstrated with their handling of the 2019 PSAT exam.

References

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.