Prioritizing and Microservices

Date Published: 15 June 2021

It's not unusual to have different levels of prioritization in backend systems. Imagine you have a process that generates and sends reports that users have requested. Some of these might be low-priority reports that are simply generated periodically so they're available to view, while others might be generated on demand, with a user actively waiting for the results. These could be further differentiated based on the user's role or whether they're a free user or a paying subscriber, etc.

How might such a system be architected?

One Server

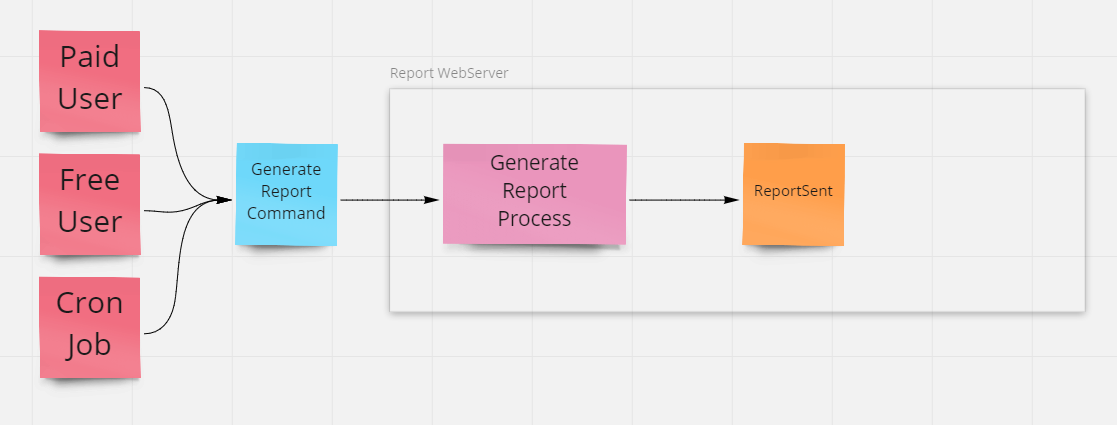

If you just have a single web server in which everything is in process, then you probably don't have much of a way to deal with these issues. Your web server will attempt to serve requests as they come in, and if some of those requests are being triggered by a service somewhere (cron job) that makes requests on a schedule to generation of prepared reports, and others are being made by free and paid users, the server is going to give all of these requests equal weight. And eventually it's going to reach a scalability limit and things are going to get rapidly slower for all users involved.

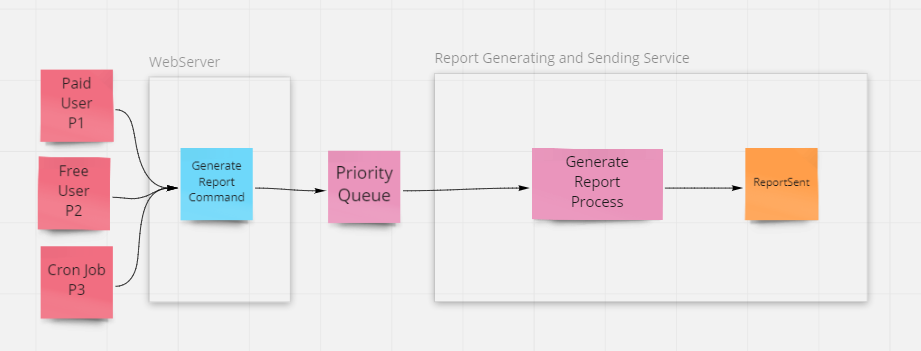

The system basically looks like this:

The first step to enable prioritization, then, is to decouple the handling of requests from their completion. We can't change the way HTTP works and even low-priority users should have their requests processed in a timely manner, even if the final product of their request isn't immediately available. So instead we'll complete the request quickly and let the user know their request has been received, and that they should check their inbox for the requested report when it's ready (or for the scheduled jobs, they will simply be published to their destination).

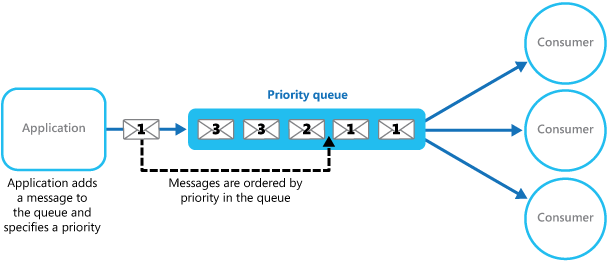

Separate Web Server and Backend Processor

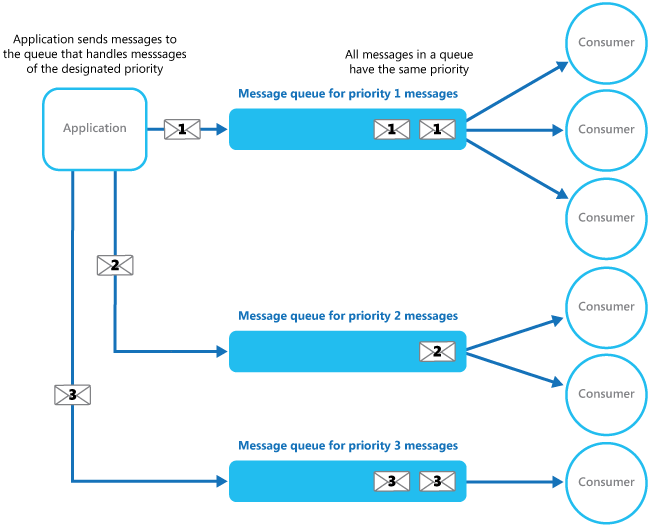

One approach to the problem now is to have each request complete quickly, but generate a command which is placed into a priority queue. The priority queue pattern is a variation of a typical First-In-First-Out (FIFO) message queue, except that new messages are inserted into the existing queue ahead of less important messages. Typically priority 1 is the most important, and so these messages are placed into the queue in front of priority 2 or priority 3 messages. If you've been to an amusement park where some folks have a "fast pass" ticket or wristband that let's them cut in line, it's that same sort of idea.

The "fast pass" holders still have a queue, but they only need to wait behind other pass holders (though in the real world scenario the constrained resource - the ride - splits its availability between fast passers and non-fast passers because otherwise the lower priority riders would never get to ride).

Adding a priority queue to the webserver-based system yields this architecture:

At this point, as far as we know, the commands should be processed in priority order. Assuming the report generating and sending service only pulls new items from the queue as it completes other requests, it should always pull the most important command next. If it doesn't behave this way, and instead it pulls things from the queue faster than it processes them, it's possible that lower-priority items might impact the processing of higher priority ones.

There's also the potential problem that lower priority commands may starve and never be processed, or at least not for a long, long time, if there are always higher priority commands coming in. This is exactly why amusement parks don't just let fast pass-holders cut directly into the front of the line of non-pass holders, but instead they throttle both queues and alternate pulling riders from each according to some policy or algorithm. With cloud services and "infinite scale", though we can configure multiple back end processes to serve each queue, so in effect riders in each queue would be waiting for separate but identical rides.

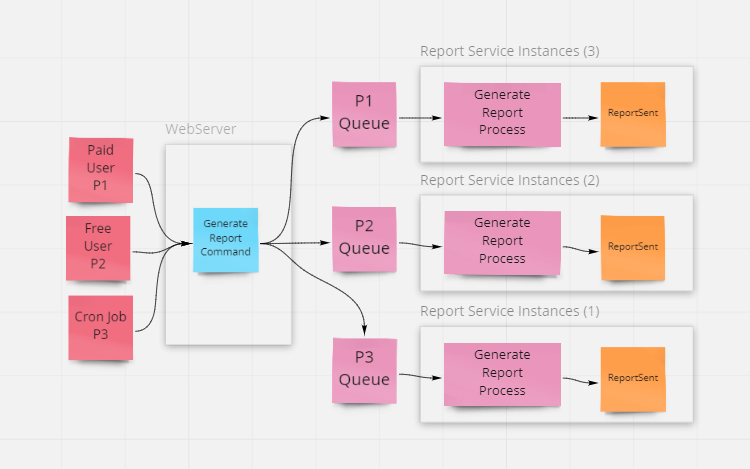

Separate Web Server and Multiple Backend Processes

The address the issue of low priority commands never being processed, or because priority queues may not be a feature supported by the chosen messaging infrastructure, another approach can be used. This is called the competing consumers pattern, and it can use separate queues for each priority, with one or more consumers processing each queue. The processors can be scaled independently based on queue length, CPU load, etc.

Using separate queues based on priority would yield a design like this:

This approach works well. It ensures that all priorities are serviced but that higher priority requests receive more resources. Each priority can scale independently if necessary.

But let's revisit the assumption we made above, which was that the "report service" behaves in a FIFO manner and doesn't start more work than it can handle. Let's assume rather than it being as single service, there are actually a number of microservices in play. Also, let's consider how these services interact, with a brief side trip.

Microservice Communication and Dependencies

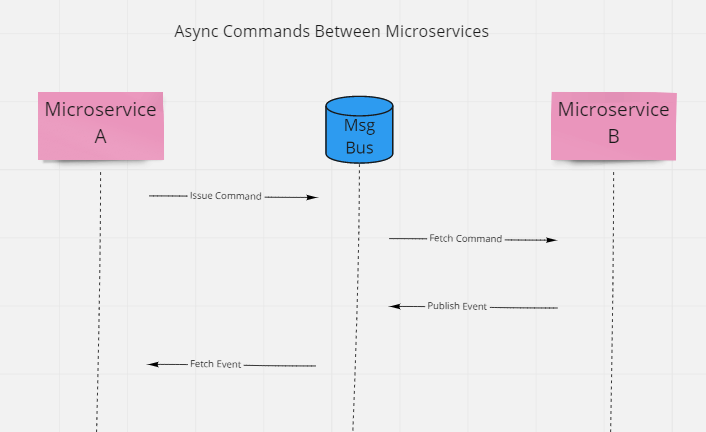

Microservices frequently need to communicate with one another in order to accomplish their tasks. One obvious way for them to do so is via direct, synchronous calls using HTTP or gRPC. However, using such calls introduces dependencies between the two services involved, and reduces the availability of the calling service (because when the destination service is unavailable, the calling service typically becomes unavailable as well). This relationship is described by the CAP theorem (and PACELC) which I've described previously.

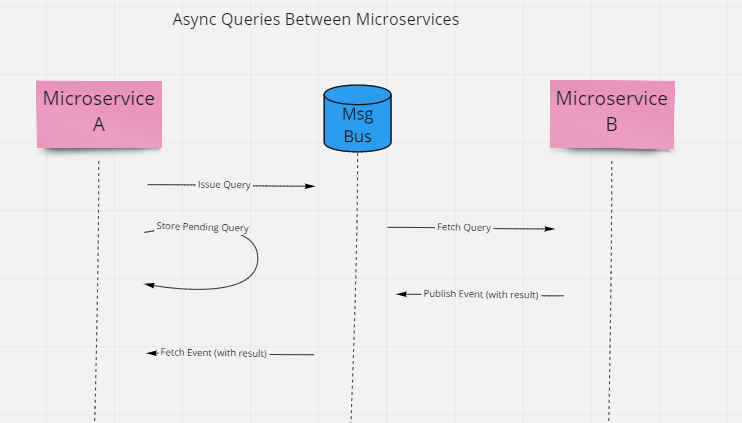

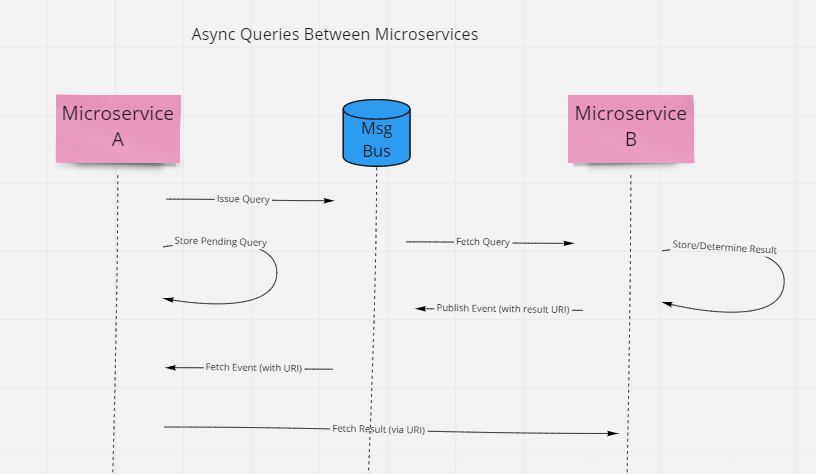

An alternative approach to direct calls that improves availability and reduces synchronous coupling is to use asynchronous messaging infrastructure to communicate between the two services. For example, one service can issue a command via a queue, and another service can read the command from the queue and process it. If any response is necessary, the processing service publish an event, which the initiating service can subscribe to and consume.

This is fine for commands, but what about queries? With queries, frequently the user is waiting for the request to complete, or some other process is blocked until the query response returns. You can implement queries using the same architecture, though, it just means the calling service needs to store its state (so it can move on to other tasks) and then restore that state when the results are returned (in the event published by the query processor).

Of course, if the query result isn't small, it probably shouldn't be attached to the event, in which case a URI can be used to represent the result.

The URI might be on the query processor microservice itself, or it could be in external infrastructure, such as blob storage.

Ok, now we've seen how async queries and commands can be used to reduce realtime dependency between microservices. What does this have to do with prioritization?

Prioritization with Async Processing

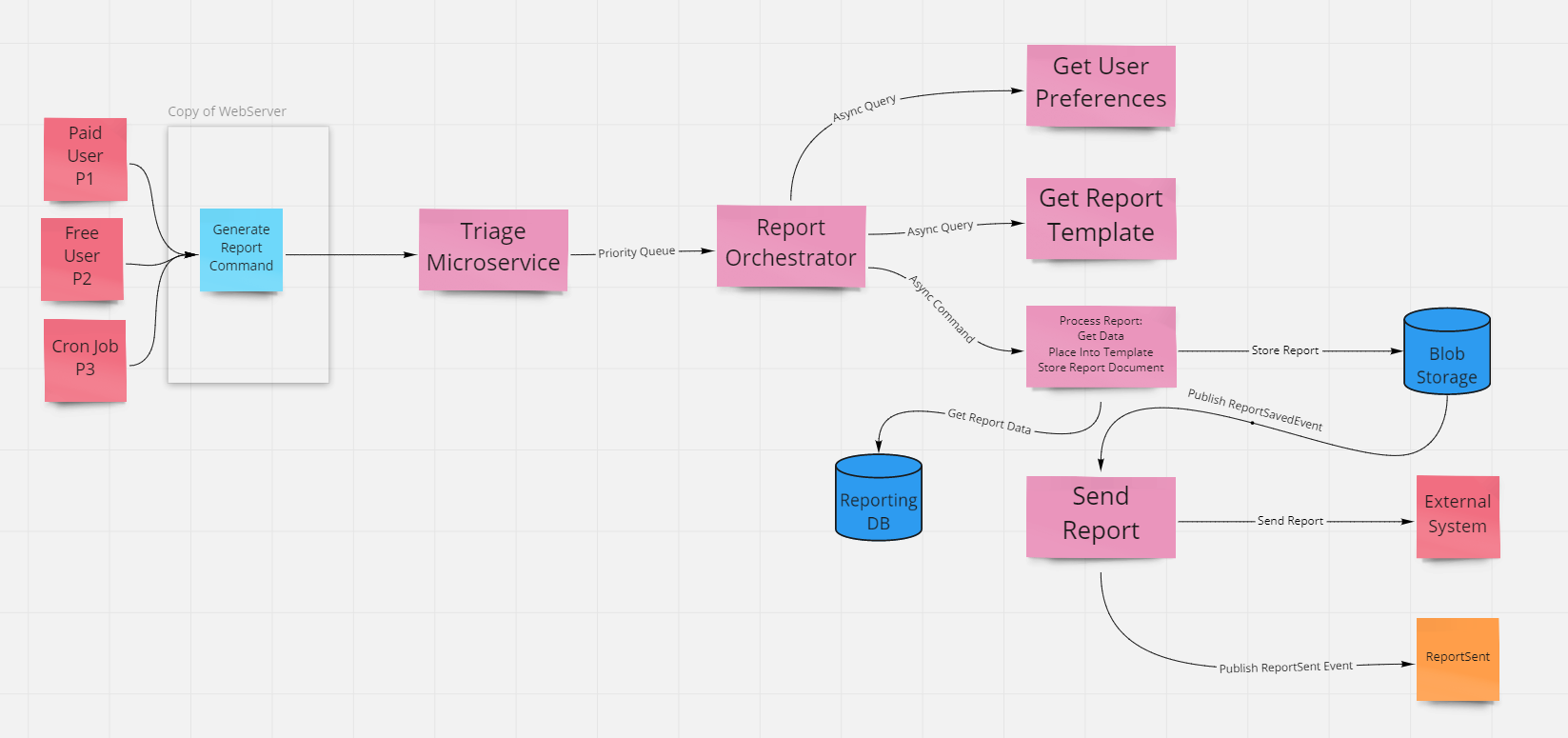

Imagine that the simple "reporting service" described at the start of this article has been implemented using a set of microservices. These services have the following responsibilities:

- Triage. Responsible for receiving commands and placing them into the priority queue in priority order.

- Orchestrator. Responsible for gathering user preferences and the require report template and initiating a command to fill the template with data.

- Get User Preferences. A CRM or similar system that stores info related to how the user wants to receive reports.

- Get Report Template. A service that stores report templates.

- Process Report. Responsible for getting the actual report data, populating the template with it, and storing the resulting document. Once stored, an event is published which includes the necessary information to send the report.

- Report Sender. Listens for events published when report documents are stored and sends the associated report via an external service. Publishes ReportSent command.

Now assume that many of these relationships use async communication patterns as described above, with (standard, non-priority) message queues between the various services used to process commands as well as queries. Here's the overall structure:

So, a paid user requests a report. The Triage services throws it into the priority queue (as priority 1 or P1) and the orchestrator quickly picks it up. The orchestrator service throws a query request onto another queue and stores the report request for later (when it gets back the query result.)

In the meantime it keeps on processing additional commands coming in from the priority queue, possibly including P2 and P3 commands.

The initial P1 user preferences query completes, and the orchestrator handles that event and makes another async query to get the report template. Then it goes back to doing other things.

Finally, that report template query completes, and the orchestrator handles that event and sends a command to the Process Report service to do its thing and ultimately send the report.

Assuming there are no other commands in flight, this all works as quickly as it can. But what if a scheduled Cron Job is in progress when the paid user's request comes through? Let's say the Cron Job has submitted 100 low priority P3 commands for reports, and the Report Orchestrator has pull 20 of these commands already when the P1 paid user command comes in.

The P1 job will jump ahead of the 80 remaining commands in the priority queue, and the orchestrator will pick it up when it gets to it, and then it will make an async query to get user preferences. After which, it will continue to busy itself with handling other async query results coming back as well as processing additional incoming commands from the priority queue.

Subsequent P3 requests may jump ahead of the P1 request as their queries are returned more quickly. Subsequent P3 commands being processed may consume shared resources, such as on the reporting database, that further block or delay the P1 request, even though it entered the process before these lower priority requests. The strict service level agreement (SLA) that has been committed to paid users may be put at risk or violated due to low-priority requests entering the system at the same time as the high-priority request.

What is the problem?

The issue with this approach is that the prioritization is only applied at the entrance to the system, and is not enforced within it. This is exacerbated by the fact that the report orchestrator has no FIFO expectation and in fact can begin work on an arbitrary number of commands at the same time, potentially resulting in a very large amount of work in process (WIP). We can use Little's Law to understand how WIP impacts the time it takes for requests to move through a system, which can impact high priority SLAs. Constraining total WIP on the system, or at least on the orchestrator, would mitigate the issue.

You can see how this is true by imagining if the work in process were limited to one at a time. Constraining the whole system down to a WIP limit of 1, would optimize the speed with which any individual report request would be fulfilled (while also reducing the total throughput of the system in terms of total reports sent/minute). Every individual microservice would sit idle, ready to go at a moment's notice, with nothing in line ahead of any incoming request.

The introduction of queues between systems increases both WIP and cycle time. It optimizes for keeping individual systems busy, optimizing for productivity, not performance (cycle time). This only becomes apparent when performance is required and the system is already under load. Customer SLAs are written based on individual request performance, not overall system efficiency or throughput.

There's nothing to prevent the entire set of microservices - except the triage service - from being duplicated, with one set for each priority level. Further, each of the services could be configured to autoscale as needed. This competing consumers approach would ensure that P1 requests were not adversely impacted by lower-priority work, but only if potentially shared resources like the reporting database and the external email system were duplicated as well.

If a single external email system were used by all of the duplicated services, for instance, it could still be a bottleneck. Imagine if it had a maximum throughput of 100 emails per second. It could easily be backed up processing P3 emails, such that any P1 request would need to wait in line behind the P3 requests before being sent.

Prioritize All The Things

Another option is to lean heavily into priority queues, and use them everywhere in the system, including between every microservice. Using this approach, it's still possible that lower priority work would compete with high priority work because its queries are faster (for things like getting preferences or templates) or because its report data can be fetched more quickly (from the Reporting DB). But at least if the system is under load and queues have non-zero length, the P1 command will jump to the head of the line every chance it gets. It's not necessarily going to be as fast as if the WIP limit were 1 or if there were identical separate systems for the P1 tasks, but it would help.

Side Note: In my Kanban: Getting Started course on Pluralsight I talk about how queues and WIP and Little's Law work, and how kanban systems can use techniques like swim lanes to deal with high priority requests.

Tracking and Limiting WIP

In this design, if you wanted to limit overall WIP, one way you could do so would be in the orchestrator service. By having it subscribe to the ReportSent event, it could keep track of reports that were in flight and mark them as completed when the associated event was received. In this way, the overall WIP of the reporting system could be limited to a configured value. If necessary, this could be configured to take into account priorities, so that for example maybe a maximum of 2 P3 requests could be in flight at any given time, 4 P2, and 8 P1, for a total of 14 maximum. In any case, by restricting WIP at the orchestrator (and perhaps ideally matching it to any bottleneck introduced by the external email sender system), it forces the bottleneck upstream to the priority queue coming from the triage service, and this allows the priority queue to perform as intended (even without priority-specific WIP limits).

Summary

Prioritization works best when there is a single queue, since things can easily be prioritized and then processed in first-in, first-out order. Once a process becomes asynchronous and involves many different and possibly parallel tasks, maintaining prioritization becomes more difficult, and lower priority work can easily disrupt higher priority work. To mitigate this, prioritization can be used everywhere within a process, or processes can impose limits on how much can be performed in parallel so that slack is available to deal with higher priority requests.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.