Getting Started with Kanban

Date Published: 29 November 2011

Kanban can mean a number of things. In Japanese, the literal translation is “signboard,” but it also refers to a system of lean manufacturing, or in fact to a process for eliminating waste from a production system of any kind. In this article, I’ll quickly describe how kanban cards are used, and how the Kanban with a capital K system can be used to improve existing systems.

Examples of Kanban

If you’ve ever ordered an espresso drink at Starbucks, you’ve probably seen them write down your order on your cup. If there’s no line, the cup goes right to the barista making your drink. However, if they’re busy, the cup goes to the back of a queue, and the barista pulls from the queue until they’ve caught up and everybody has their drink. In this simple system, the cup with your order on it is serving as a kanban – a token that provides information within the system. Imagine how the system would work if there were no such token, and only one or two customers could be served at a time. Each customer would place their order, the cashier would ring them up, and everybody would wait while the drinks were made. Then, the customer would receive their drink(s), and the next customer could be served by that cashier. This process obviously would result in longer wait times and total throughput times for many customers, especially ones who were just grabbing a simple coffee, not an espresso drink. You can also think about how this parallels synchronous requests to a web application as opposed to a web application that simply places requests into a queue for another process to complete work on, but that’s beyond the scope of this article.

In the classic example of Kanban use in a production system, the actual kanban cards resided on parts bins in a factory. Their purpose was to keep inventory to a minimum and provide a signal within the system for replenishment of queues. At a particular assembly station requiring a certain component, a bin full of the components would be present. The worker or team at this station would take from the bin as they completed their assembly work. When the bin runs out of parts, it is swapped out for a full one from the factory’s on-site storeroom. Within this storeroom, an empty bin provided a signal that more parts were needed. The storeroom staff would swap out the empty bin for a full one from the supplier (perhaps the next time the supplier made a delivery, or by going to the supplier themselves). Thus, at any given time there are 3 bins in play (one at the assembly point, one at the local storeroom, and one at the supplier), and so this is typically referred to as a Three-bin System.

Kanban for Project Management

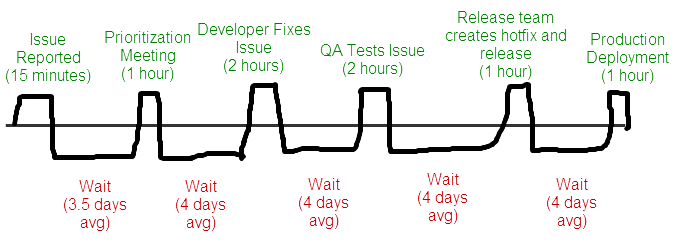

In the realm of software projects, Kanban can be a useful tool for eliminating waste and improving agility. The main goal of Kanban is to identify and eliminate bottlenecks and waste, and to increase throughput through the system. It is specifically not a goal to maximize the efficiency or utilization of all personnel involved in the system. A common first step in apply Kanban to an existing system is to create a Value Stream Map. This process involves identifying all of the steps a unit of value goes through from inception to delivery, noting both productive and wasted time. For instance, if you’re working in a support department dealing with bugs reported by end users, you might have a process that involves these steps (this represents just one possible workflow through the system):

- Customer reports an issue to Support

- Management prioritizes the issue

- A Developer is assigned the issue and creates a fix

- QA tests the issue and ensures no regressions were created

- Release team schedules the issue for a release and creates a hotfix for the customer if required

- Fix is released in a publicly available software update

Each of these steps is required in the process, and the goal here isn’t to change any of them, but merely to identify where the value and time is being spent. What’s missing in the above process, though, is the time spent on each of these actions, and the time spent between them. Typically, there are queues between each of the above stages, and some of the events only occur at certain points in time. For instance, management isn’t going to prioritize each issue as it arrives. More likely, they’ll hold a prioritization meeting on a scheduled basis, perhaps once every week or two. Likewise, releases typically don’t occur with every bug fix, but rather on some kind of a schedule or at least only when the amount of new features and bug fixes warrant a release.

If we say that reporting the issue takes 15 minutes, and the other steps each take an hour or two, and in between each step we have an average of 4 days of wait time (except for the weekly prioritization meeting, which averages 3.5 days since it happens weekly), then we can create a Value Stream Map like this one:

Adding up the productive and wasted time, we get:

- Value-Adding Time: 7 hours, 15 minutes

- Wasted Wait Time: 19.5 days

- Total Time (Cycle Time): 19 days, 19 hours, 15 minutes (19/8 days or 475.25 hours)

Once this information is visible, tweaks can be made to the system to improve the overall flow and reduce the wasted wait times. This is typically done by reducing the amount of Work In Progress (WIP), because the only other way to achieve an increase in throughput is to add additional production capacity (everybody in the system above is already fully utilized). Little’s Law states that the average total time of an item through the system (also known as cycle time) is inversely proportional to the number of items in the system. That is, Cycle Time = Work in Progress / (Work Rate). The Work Rate in the above scenario would be 1 bugfix per 7.25 hours. Thus, the Cycle Time must equal the WIP*7.25, which for a Cycle Time of 475.25 hours means a total WIP of about 65 items.

If the total WIP were reduced to 30 items, and nothing else in the system changed, then bug fixes would be completed on average in 9 days, not 19, a 52% reduction. That’s the promise of Kanban. As cycle times drop, the value of each work item is increased, as customers see their bug fixes and feature requests sooner, reducing the feedback loop, and trust begins to develop that things can get done in a reasonable amount of time, so customers and management do not feel like they need to try and cram as much as they can into a given sprint or release cycle.

Kanban Boards

One way to reduce WIP is to visualize each of the states a work item goes through in the system and to limit the number of items that can be in any given state at one time. When a downstream state is at its maximum WIP, the upstream states need to stop production and do something else. They can either assist the downstream state, which might mean that developers jump in and provide some help to QA or the Release team, or they can catch up on other activities that are needed (documentation, refactoring, training, system automation, etc.). It’s not a bad idea to keep a separate improvement board that has the team’s prioritized list of things they would like to do to improve their system, which people who are blocked downstream can use to decide what to work on until the system is flowing again. If the system is constantly blocked at the same point, then this makes it visible to everybody that additional resources are required at this point.

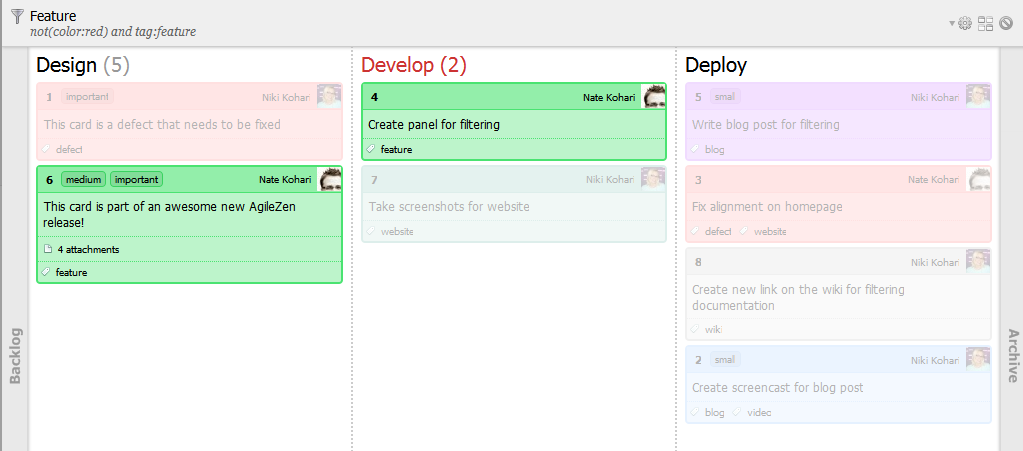

Most kanban boards are created using post-it notes on a whiteboard, but there are many electronic options available as well. One I’ve used successfully is AgileZen, shown here:

Using an electronic kanban board, you can easily keep a distributed team synchronized. Each state supports the notion of a WIP limit, shown above as the number in parentheses in the heading. The Develop (2) state is currently full, which is why it’s shown in red.

Summary

Kanban is a process improvement technique that can identify waste and improve the responsiveness of a production system. By visualizing time wasted in queues, identifying bottlenecks, and helping to reduce work in progress, kanban allows work to quickly flow through a system. If you’d like to learn more about kanban, I recommend the book Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business by David Anderson.

To learn more about Kanban, watch my Pluralsight course, Kanban: Getting Started.

Originally published on ASPAlliance.com

Tags - Browse all tags

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.