Estimates Are Wrong

Date Published: 07 October 2020

This is the third of the 5 Laws of Software Estimates. I expanded on the second law of software estimates in my previous article.

Nobody should be surprised when estimates are wrong, they should be surprised when they are right! If estimates were accurate, they'd be called exactimates.

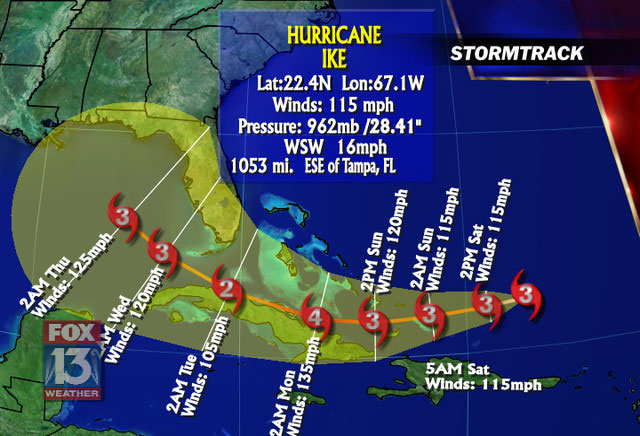

Think about weather forecasting. Even with all of the software modeling and vast arrays of sensors we have in the 21st century, we still often fail to predict the local weather more than a couple of days out. Sure, if there's a big storm brewing, we'll often have an idea of when and where it might hit land, but if on Monday you need to know if it's going to rain on Saturday you'd better be prepared for the forecast to be wrong. Forecasts aren't the same as estimates, but they share many qualities, chief among them is that errors in their calculation compound over time. You can visualize this by looking at the Cone of Uncertainty typical of a hurricane path forecast:

At the time of the forecast, the present position of the storm is known, as are various factors that can be used to predict its future location. Estimating its position in a few hours' time can be done with a high degree of confidence, but the further out in time one looks, the less confident one can be of any one specific path. The cone represents the range of likely locations where the storm might be at any given point in the future. The cone widens as one looks further out into the future because errors in how we estimate its path compound over time. The central orange line shown will almost certainly be very close to the storm's actual path at first, but a few days into the future it's highly unlikely the storm will remain exactly on that path.

The more time involved, the greater chance of errors impacting the estimate. This doesn't just apply to calendar time, but also to work effort. A task that is very similar to one you completed yesterday in an hour you could predict that you could also do today in about the same time, maybe even less. The total time involved in the effort of the task is relatively small. However, it's far less likely that you could say with any exact degree of confidence that a project similar to one your team of 10 people completed in 6 months will take exactly 6 months to complete. There's so much more time involved there that the likelihood of unforeseen events altering the estimate is almost certain.

One way to work around the inherent inaccuracy of estimates is to shift from using estimates given in absolute units to estimates given with a degree of confidence. Rather than saying a given task will take 3 days to complete (or, say, 5 points, whatever that means), you could instead offer best-case and worst-case estimates that reveal the cone of uncertainty and provide useful information for planning. You might offer that you estimate the task could be completed in a day if everything went right and no obstacles were encountered, but that you have only a 10% confidence in this happening. You're 50% confident the task would be done within 3 days, and you're 90% confident it will be done in 5 days. Of course there's always a chance that even after 5 days, the task might not be done, perhaps due to sickness, external dependency, power outage, or any number of other chance events.

Now, if you're using estimates to prioritize work, you may find it helpful to try to minimize the size of the work items you're prioritizing, since smaller scoped items are more easily and more accurately estimated. By reducing the size of work items, you're also helping maximize flow of work through the system (see my Kanban Fundamentals course for more on this). That means your stakeholders are getting feedback more rapidly, so they'll be better able to prioritize future work. In addition, smaller-scoped tasks don't vary in effort to complete as much as larger-scoped tasks, because there is less compounding of random chance and errors in estimation. This means that actual time to complete work will typically be closer to the estimated time - the standard deviation will be less. When the average estimate is a reasonable stand-in for any given work item's actual estimate, the value of spending time on an actual estimate starts to erode.

If you spend time estimating every small work item, but in the end they're all still small and they all are completed within a reasonable variation of one another, the estimates don't add much (if any) value. Instead of spending time estimating, many teams instead choose to spend that time breaking down large blocks of work into smaller work items that can be completed by the team quickly. This increases flow while still allowing stakeholders to prioritize just as effectively, if not more effectively, than if that time were spent trying to estimate the larger blocks of work.

Estimation Error Approaches Zero... Eventually

Clearly, the accuracy of estimates varies with time. The further out an estimate is made, the more likely it is to be wrong and the larger the cone of uncertainty (the scope of the error). Estimating work that won't even be started for quite some time is far more likely to have large errors than estimating work that will be started today. Estimating the total time it will take to complete work that is in progress is typically more accurate than before it's begun. And of course, "estimating" how long it will take to complete work that you've already done (assuming you tracked your time) is the most accurate of all.

Looking out into the future from a fixed point in time, entropy and random chance make accurate estimates increasingly difficult the further into the future you go. But on the flip side, for a point in time in the future, the cone of uncertainty shrinks as the present time approaches, narrowing to a single point once present time reaches it, and remaining there forever once it's in the past. If accuracy is paramount, the most accuracy will be achieved by minimizing the amount of future time that exists between when the estimate is made and when the task is complete. Sometimes teams can use this information to better determine when and how to make or update their estimates.

Learn more about the 5 Laws of Software Estimates, and share your own experience in the comments below.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.