Encapsulation Boundaries Large and Small

Date Published: 28 January 2020

Writing any significantly complex software application involves the use of encapsulation boundaries and abstractions. Think about the smallest bit of executable code in your program: an expression or perhaps a statement. This typically maps roughly to a line of code. You can build entire applications using only this structure. If you do, they look something like this:

A program made up of a sequence of statements.

However, beyond a certain point, long lists of statements become difficult for humans to reason about. So we find ways to group them together into cohesive chunks of code, and we create and enforce constraints that help us isolate these chunks of code from other chunks of code.

Functions

Functions (or methods) provide a way to group sets of statements. They also provide the isolation boundaries we need to be able to reason about the internal state of a function without being overly concerned about all the other code in the program. This is possible because of the encapsulation functions provide, scoping local variables and forcing interaction with the function to (generally) go through input arguments and returned results. Functions that only do this are referred to as pure functions and are generally easier to reason about than those that depend on or modify application state outside of the function through whatever means.

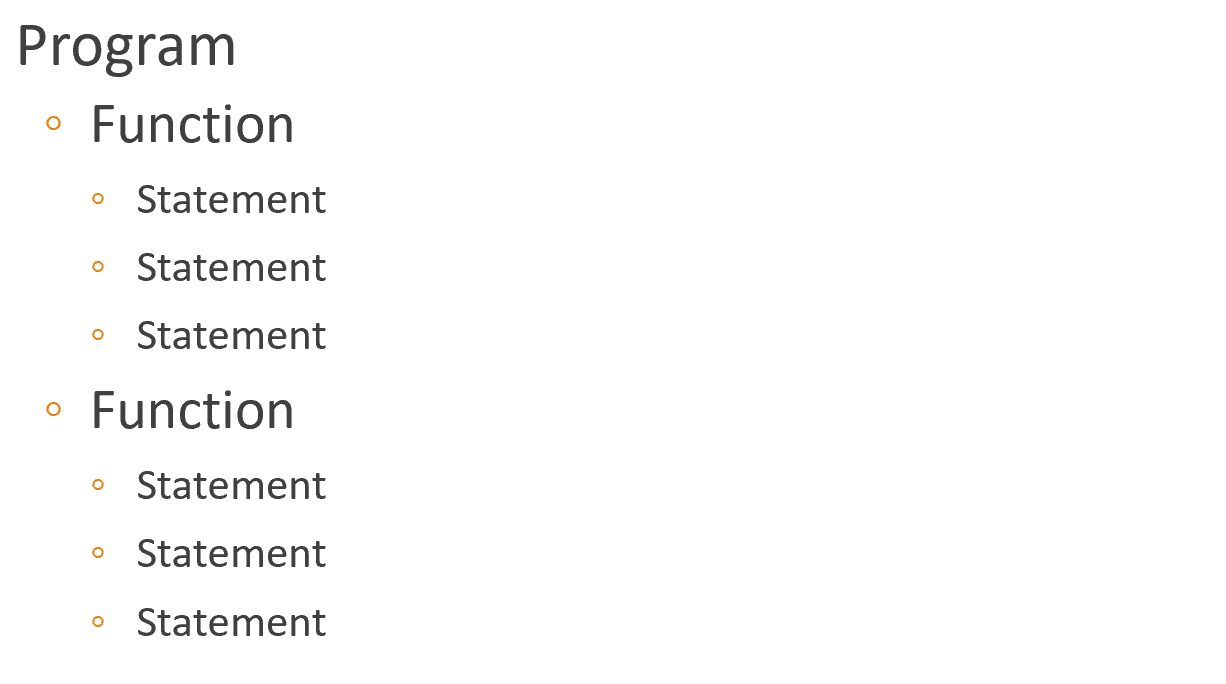

Once we have a longer program that requires functions for organizational purposes, it might look something like this:

A program made up of several functions.

However, this too can grow unwieldy, and it may be helpful to group related functions into cohesive groups with their own encapsulation boundaries and constraints.

Classes

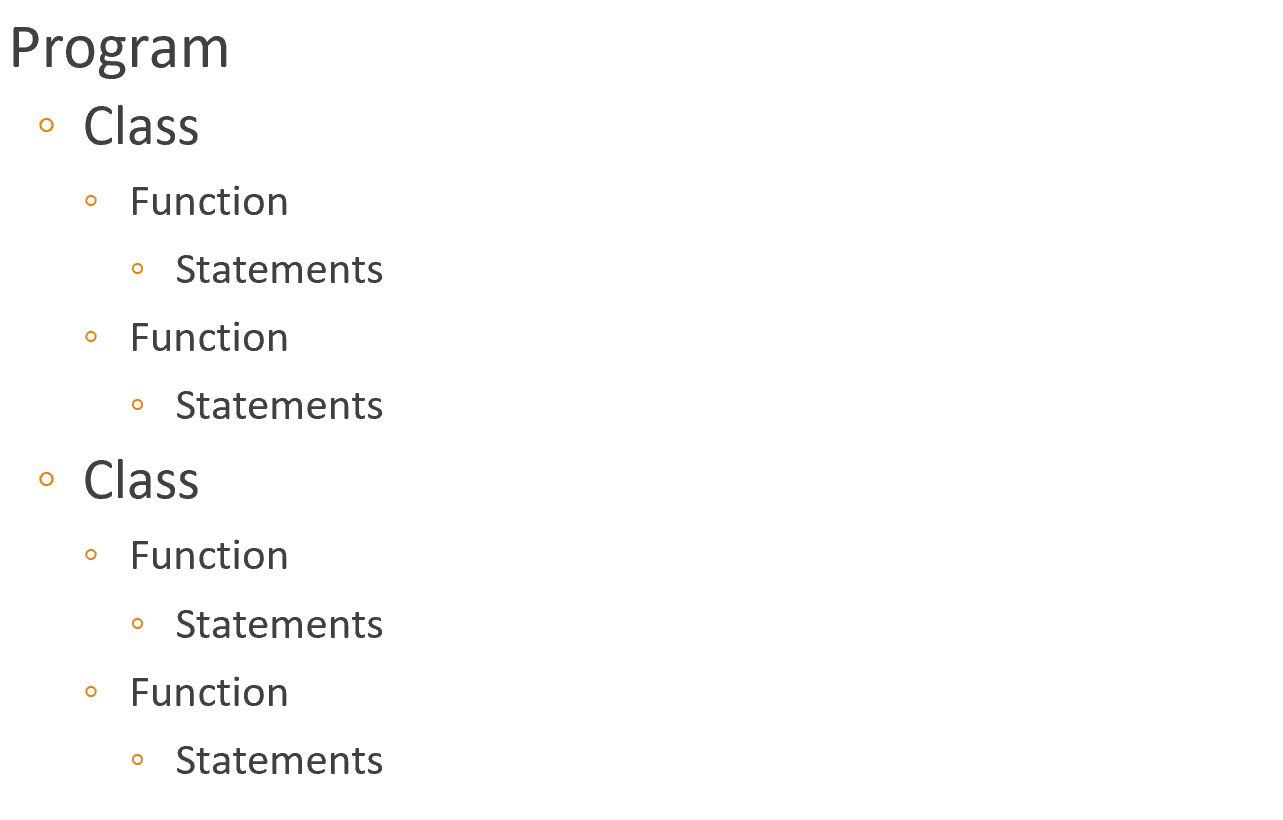

In languages like C# and Java, the next level of encapsulation boundary is the class. Of course, in these languages you actually had to have a class and a function from the very beginning to serve as your application entry point, but ignoring that syntactic requirement this is the point at which you can start to group together the functions that your program uses to do its work.

Like functions, classes offer scoping and protections against access. Within a class, we can generally reason about the behavior and data of the class without regard for other parts of the system. We should be able to isolate the class from the rest of the application, both in theory and ideally in practice, allowing for unit testing of the class. Our application starts to look like this:

A program made up of classes and their functions.

For many small programs, this may be all that's required. However, if the program continues to grow in size and complexity, it may be useful to continue breaking it up into cohesive pieces.

A good rule of thumb for looking to break things up is about 10. A function with more than 10 statements might be worth breaking into two functions. A class with 10 functions probably could stand to be two classes. This isn't a strict rule, but as a rule of thumb it lets you do easy math on the size and complexity of your code and whether you need additional "buckets" to compartmentalize the code into. A program that only uses Classes, Methods, and Statements might work for up to about 10 classes, so about 100 methods, or about 1000 lines of code. Yes I'm just making this up but bear with me as I have a point to make later, and it doesn't really matter if sometimes it's 3 things and sometimes it's 30.

Once you have more than about 10 classes, it may be time to think about ways to organize them better. Generally at a minimum you'll use folders and namespaces to group related classes together. This helps with organizing and discovering the classes, but does nothing from an encapsulation perspective. Usually the next step is to break up the classes into different cohesive buckets that offer some level of encapsulation.

Projects

Projects or modules provide additional isolation for groups of classes. In C# you can use the internal keyword to restrict access to certain classes from outside of their current project/assembly. You also can restrict access by configuring dependency direction between projects. If project A depends on project B, then types in A can use types in B. But, importantly, types in B cannot use types in A.

Projects also provide a seam in how we deploy software. We can choose which assemblies or packages to deploy on a project-by-project basis, something we couldn't easily do with individual classes or methods. Using project artifacts we can update parts of applications, rather than having to replace them in their entirety. At this point our system looks something like this:

A program made up of several projects.

This is where a lot of teams stop with the whole grouping and encapsulating business. In most cases, teams work on applications within organizations, and most organizations have more than one application, so the end result looks something like this:

Several programs within an organization.

Thinking back to our logarithmic progression (up to about 10 things per containing structure), this organization has 5 levels of encapsulation from programs to statements. That caps their total size at about 10^5 statements, or 100,000 statements.

Now, ideally these programs would themselves be perfectly encapsulated from one another. However, in practice they're often conjoined by common infrastructure. The most egregious offender is a shared database. A shared database is to multiple projects what global state is to an object-oriented program. It provides a mechanism for bypassing all encapsulation and changing state without the behavior designed to accompany that state. This makes it much more difficult to reason about any one piece of the application, because it's no longer perfectly isolated.

Bounded Context

Domain-Driven Design offers several patterns to help manage complexity in software applications. One of the most important is the bounded context. I've seen designs place multiple bounded contexts within an application, but more often I see bounded contexts wrapped around one or more application, and that's how I typically model things, so I'm going to use that here. When you use a bounded context, there are two parts to it. A context, in which a given domain model is valid and appropriate, and a boundary. This should be an encapsulation boundary, just like that offered by a project, class, or function. Things outside of the boundary should not be able to access things within it unless they go through an established interface. Organizing your programs into cohesive bounded contexts (that may to specific problem domains or subdomains) results in a design like this one:

Programs within bounded contexts.

Now, one of the most important parts of our application is the domain model. That's where our business logic should all reside. Complex applications will often have many entities within their model, which when changed need to be kept in a valid state before they're persisted. When the number of entity classes grows beyond a certain size, they can be difficult to work with. Complex related groups of classes may be modified and persisted in piecemeal, leaving the group in an invalid state.

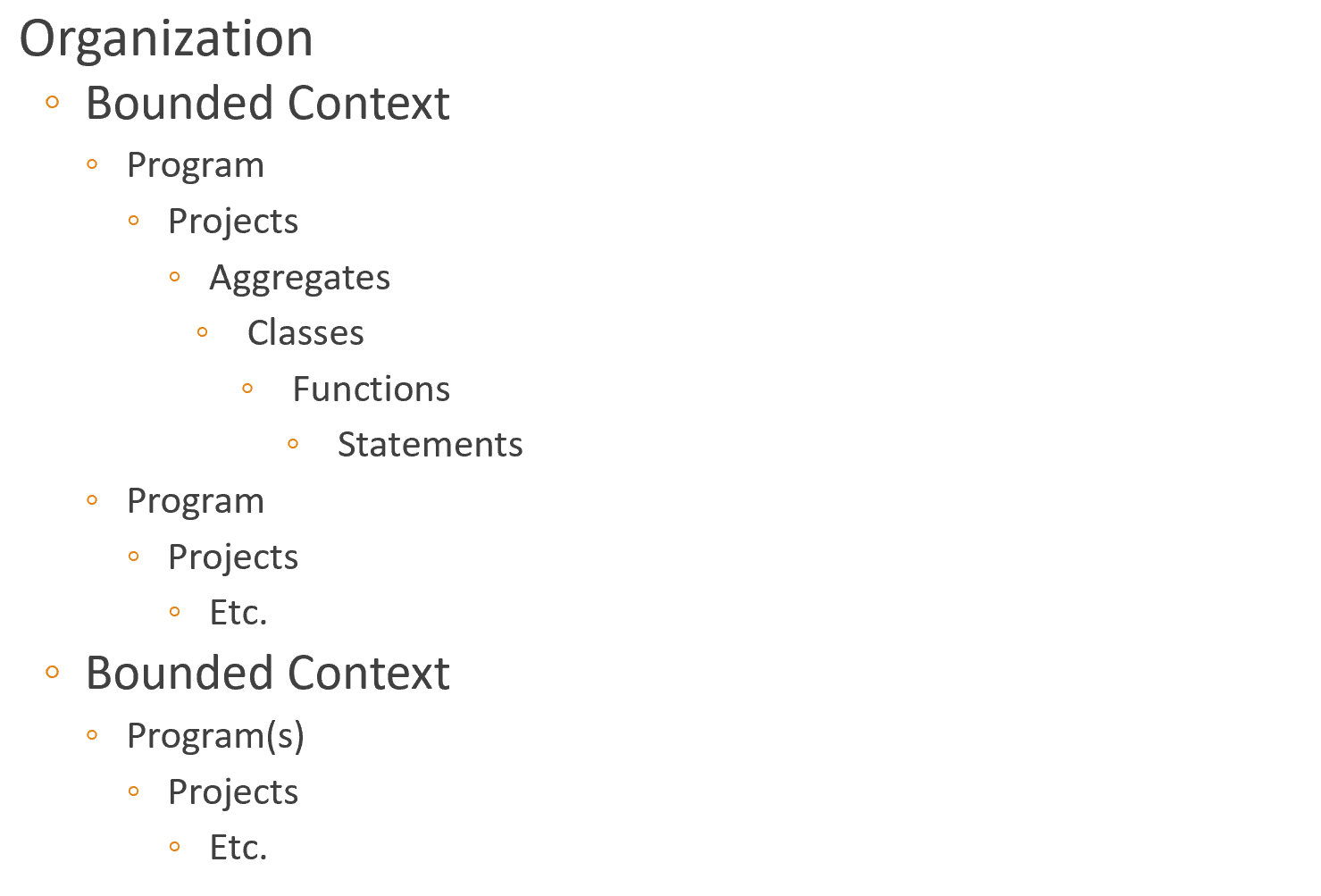

Aggregates

Domin-Driven Design offers another pattern to address this: aggregates. An aggregate is a group of classes (entities) that should be read from and written to persistence as a single unit. Grouping entities together into cohesive aggregates reduces the total number of things developers need to reason about in the domain layer, and aggregates can provide yet another encapsulation boundary to help reduce cognitive load and deal with complexity. Frequently you'll want to enforce a rule stating that all persistence operates on aggregates, not entities, in which case every entity becomes part of an aggregate (even if it's an aggregate of one).

The resulting code organization then looks something like this:

Projects may contain aggregates that group related entities together.

Other kinds of projects might offer other class grouping structures as well. For instance, a UI project might group related classes into controls or components that would offer cohesive and encapsulated behavior. The point is that if your highest level coding structure in your system is a class, your codebase may have difficulty scaling up to support more complex problems.

Domain-Driven Design is meant to tackle complexity. One way it does so is by introducing additional encapsulation boundaries and buckets in which to group cohesive chunks of application logic. Bounded contexts and aggregates are two such ways it does so. While I don't expect most bounded contexts to have 10 projects or most aggregates to have 10 entities in them, if we continue assuming a logarithmic progression in the complexity this can support, we're now up to 7 levels of encapsulated abstractions in the system. That means it can support roughly 10^7 or 10,000,000 statements.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.