What is the difference between a DTO and a POCO (or POJO)

Date Published: 16 February 2021

Two terms that come up frequently when discussing software development in .NET and C# are DTO and POCO. Some developers use these terms interchangeably. So, what is the difference between a DTO and a POCO? First, let's define each term.

Data Transfer Object (DTO)

A DTO is a "Data Transfer Object". It's an object whose purpose is to transfer data. By definition, a DTO should only contain data, not logic or behavior. If a DTO contains logic, it is not a DTO. But wait, what is "logic" or "behavior"? Generally, logic and behavior refer to methods on the type. In C#, a DTO should only have properties, and those properties should only get and set data, not validate it or perform other operations on it.

What about attributes and data annotations?

It's not unusual to add metadata to a DTO in order to have it support model validation or similar purposes. Such attributes do not add any behavior to the DTO itself, but rather facilitate behavior elsewhere in the system. Thus, they do not break the "rule" stating that DTOs should contain no behavior.

What about ViewModels, API models, etc?

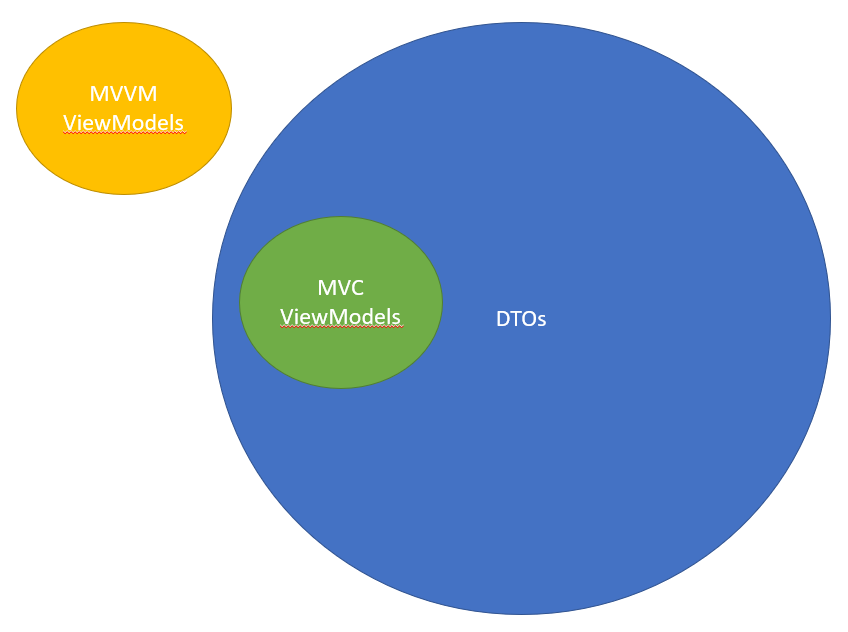

The term DTO is extremely vague. All it says is that an object consists only of data, not behavior. It says nothing about its intended use. In many architectures, DTOs can serve a number of roles. For instance, in most MVC architectures with Views that support binding to a data type, DTOs are used to pass and bind data to a View. These DTOs are typically called ViewModels, and ideally they should have no behavior, only data formatted as the View expects it. Thus, in this scenario, a ViewModel is a specific kind of DTO.

A ViewModel (used within MVC) is just a DTO with an intention-revealing name.

However, be careful. You can't then conclude that all ViewModels are DTOs, since in MVVM architectures ViewModels typically include a great deal of behavior. So, it's important to consider the context before making any broad assumptions. And even in MVC apps, sometimes logic is added to ViewModels, such that they are no longer DTOs.

Whenever possible, name your DTOs according to their intended use. Naming a class FooDTO gives no indication of how or where that type should be used in the application's architecture. Instead, favor intention-revealing names like FooViewModel.

Example DTO in C#

Below is an example DTO object in C#:

public class ProductViewModel

{

public int ProductId { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public string ImageUrl { get; set; }

public decimal UnitPrice { get; set; }

}Encapsulation and Data Transfer Objects

Encapsulation is an important principle of object-oriented design. But it doesn't apply to DTOs. Encapsulation is used to keep collaborators of a class from relying too heavily on specific implementation details about how the class performs its operations or stores its data. Since DTOs have no operations or behavior, and should have no hidden state, they have no need for encapsulation. Don't make your life harder by using private setters or trying to make your DTOs behave like immutable value objects. Your DTOs should be simple to create, simple to write, and simple to read. They should support serialization without the need for any custom work to support it.

Fields or Properties

Since DTOs don't care about encapsulation, why use properties at all? Why not just use fields? You can use either, but some serialization frameworks only work with properties. I typically use properties because that's the convention in C#, but if you prefer public fields or have a design reason why they're preferable, you can certainly use them instead. I would try to be consistent in your usage of fields or properties within your application, whichever you choose. There is some discussion of pros and cons here.

Immutability and Record Types

Immutability has many benefits in software development, and can be a useful feature in DTOs as well. Jimmy Bogard has written about trying to implement immutability in DTOs, and Mark Seeman takes a contrary approach in the comments to that article (and in the stack overflow question above). For me personally, I don't typically build DTOs to be immutable, as you can see from the example shown above. That may change, though, with C# 9 and its introduction of record types. By the way, another acronym you may see is Data Transfer Records, or DTRs. Here's one way to define a DTR using C# 9:

public record ProductDTO(int Id, string Name, string Description);When using record types and the above positional declaration, a constructor is generated for you with the same order as the declaration. Thus, you would create this DTR using this syntax:

var dto = new ProductDTO(1, "devBetter Membership", "A one-year subscription to devBetter.com");Alternately you can define properties in a more traditional manner and set them in the constructor. Another new feature is init-only properties, which support initialization upon creation but are otherwise readonly, keeping the record immutable. An example:

public record ProductDTO

{

public int Id { get; init; }

public string Name { get; init; }

}

// usage

var dto = new ProductDTO { Id = 1, Name = "some name" };C# record types support serialization without any special effort when using positional declaration. You may need to provide some hints to the serializer if you create your own custom constructor. As C# 9, .NET 5, and record types gain in popularity, I expect to use them frequently for DTRs.

Plain Old CLR Objects or Plain Old C# Objects (POCOs)

A Plain Old CLR/C# Object is a POCO. Java has Plain Old Java Objects, or POJOs. Really you could refer to these collectively as "Plain Old Objects" but I'm guessing someone didn't like the acronym that produced. So, what does it mean for an object to be "plain old"? Basically, that it doesn't rely on a specific framework or library in order to function. A plain old object can be instantiated anywhere in your application or in your tests and doesn't need to have a particular database or third party framework involved to function.

It's easiest to demonstrate POCOs by showing a counterexample. The following class has a dependency on some static methods that reference a database, making the class wholly dependent on the presence of the database to function. It also inherits from a type defined in a (made up) third party persistence framework.

public class Product : DataObject<Product>

{

public Product(int id)

{

Id = id;

InitializeFromDatabase();

}

private void InitializeFromDatabase()

{

DataHelpers.LoadFromDatabase(this);

}

public int Id { get; private set; }

// other properties and methods

}Given this class definition, imagine you'd like to unit test some method on Product. You write the test and the first thing you do is instantiate a new instance of Product so you can call its method. And your test immediately fails because you haven't configured a connection string for the DataHelpers.LoadFromDatabase method to use. This is an example of the Active Record pattern, and it can make unit testing much more difficult. This class is not Persistence Ignorant (PI) because its persistence is baked right into the class itself, and the class needs to inherit from a persistence-related base class. One feature of POCOs is that they tend to be persistence ignorant, or at least more so than alternative approaches like Active Record.

An Example POCO

Below is an example Plain Old C# Object for a Product.

public class Product

{

public Product(int id)

{

Id = id;

}

private Product()

{

// required for EF

}

public int Id { get; private set; }

// other properties and methods

}This Product class is a POCO because it has no dependencies on third-party frameworks for behavior, especially persistence behavior. It doesn't require a base class, especially a base class in another library. It doesn't have any tight coupling to static helpers. It can be instantiated anywhere without difficulty. It is much more persistence ignorant than the previous example, but it's not entirely ignorant of persistence, since it has an otherwise useless private constructor declaration. As you can see from the comment, that private parameterless constructor is only there because Entity Framework needs it to instantiate the class when it is reading it from persistence.

Assume, for the sake of argument, that both of these Product classes include methods with behavior in addition to the constructors and properties shown. These could be used a DDD Entities in an application, modeling the state and behavior of products within the system.

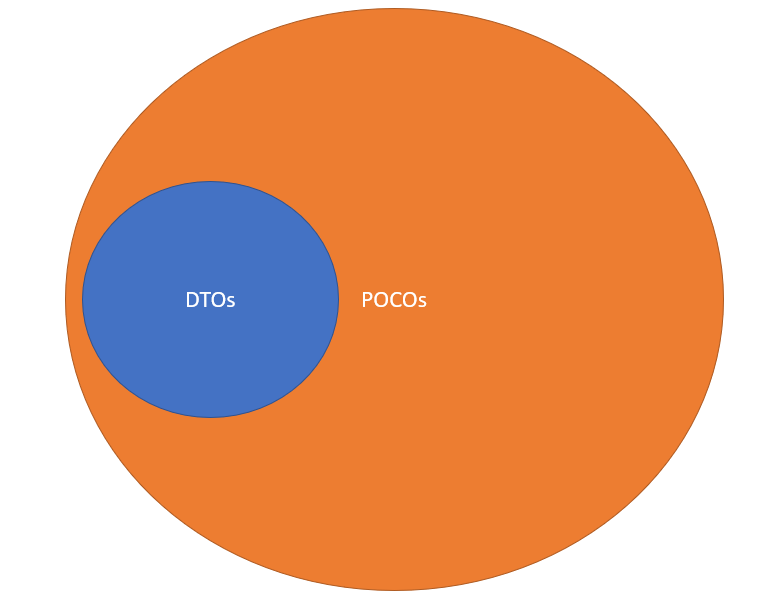

POCOs and DTOs

Ok, so we've seen that a DTO is just a Data Transfer Object, and a POCO is a Plain Old C# (or CLR) Object. But what is their relationship to one another, and why do developers so often confuse the two terms? The biggest factor, aside from the similarity in their acronyms, is probably the fact that all DTOs are (or should be) POCOs.

Remember, a DTO's only purpose is to transfer data as simply as possible. They should be easy to create, read, and write. Any dependency they might have on special base classes defined in third party frameworks or static calls that would tightly couple them to some behavior would break the rules that make the class a DTO. In order to be a DTO, a class must be a POCO. All DTOs are POCOs.

If the reverse were also true, then we could say that the two terms are equivalent. But we know this isn't the case. In the previous code example, the Product entity that works with Entity Framework has private setters and behavior, disqualifying it from being a DTO. But as we saw, it is a good example of a POCO. So, while all DTOs are POCOs, not all POCOs are DTOs.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.