Comparing Techniques for Communicating Between Services

Date Published: 24 August 2021

In distributed software applications, different services or processes or apps frequently need to communicate with one another. Modern architectural trends toward microservices and containers and cloud-native apps have all increased the likelihood that apps will increasingly be deployed not as single monoliths, but as collections of related services. There are only so many different ways these applications can communicate with one another, and each choice brings with it certain benefits as well as consequences and tradeoffs. Let's consider the options and assess each one based on its relative performance, scalability, app isolation or independence, and complexity. Also, if you're interested in this topic, you may also want to read about how to apply CAP theorem (and PACELC) to microservices.

A Simple Scenario

In evaluating each of the techniques and patterns shown below, consider that a user is attempting to complete a purchase of some products from a web application (A). The web application relies on a separate system (B) for product catalog information, including the latest pricing for each product. During the checkout process it needs to query the product catalog to get the latest price for the items being purchased. Ignore for a moment whether this is the optimal design for an ecommerce system and instead simply consider how this communication might take place.

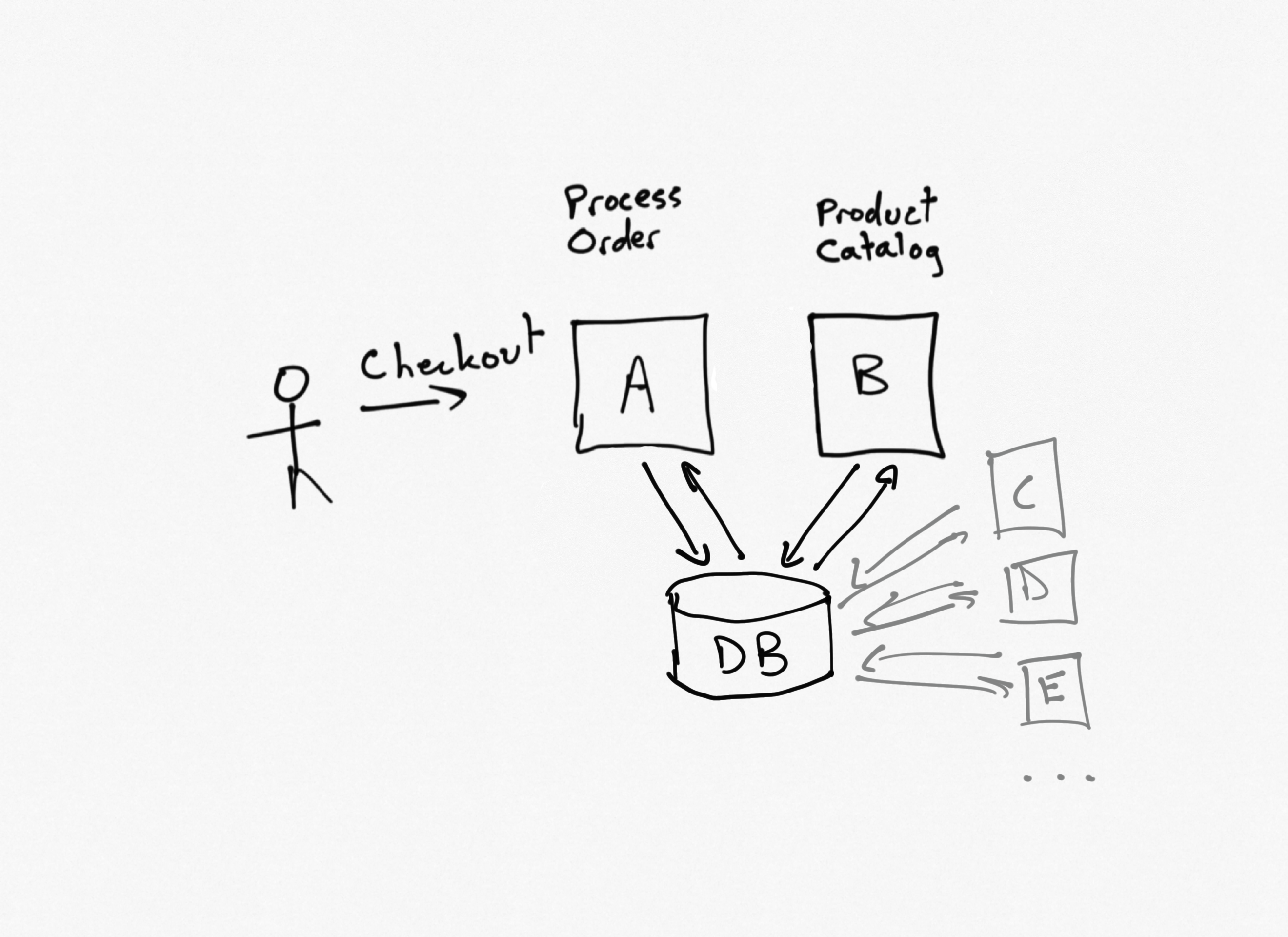

Shared Data

Traditionally, many companies would have a single database (one database to rule them all), and all of their applications would connect to it. Databases were expensive and mission-critical, so by having just one of them it made it easier to employ specialists to safeguard and optimize it. Today, data stores are commodities that can easily be deployed as part of any individual application or service, and it's widely understood that using a database as the primary mechanism for inter-process communication has a lot of negative impacts on service/app independence. After all, using a single, mutable, global container for state is a well-known antipattern in software application development, but many teams didn't realize this applied to shared databases until relatively recently.

In the ecommerce example, both the order processing service (A) and the product catalog (B) keep their data in the same database. This means that service A can simply query the appropriate table(s) to fetch the price data it needs to complete the customer's order.

Performance

A single database can provide adequate performance for a large number of requests, especially reads. However, relational databases can see performance suffer when tables grow large and are not properly indexed, or when large amounts of updates are being applied.

Scalability

Cloud providers allow individual databases to scale to massive sizes, though this is not without substantial costs.

App Isolation

The biggest problem with using a shared mutable global state as the means of integration between apps is that they all become tightly coupled to the shared state provider (database). Any time the database is down, all apps are down, and any change to the database can potentially bring down any number of apps that depend on it.

Complexity

Since most web apps need to store at least some state in an external data store, leveraging a shared data store usually doesn't add significant complexity to an application. Indeed, every app that depends on a shared database can be built just as if it were the only user of that database, with the caveat that it can't make any breaking changes to the database without potentially breaking other apps.

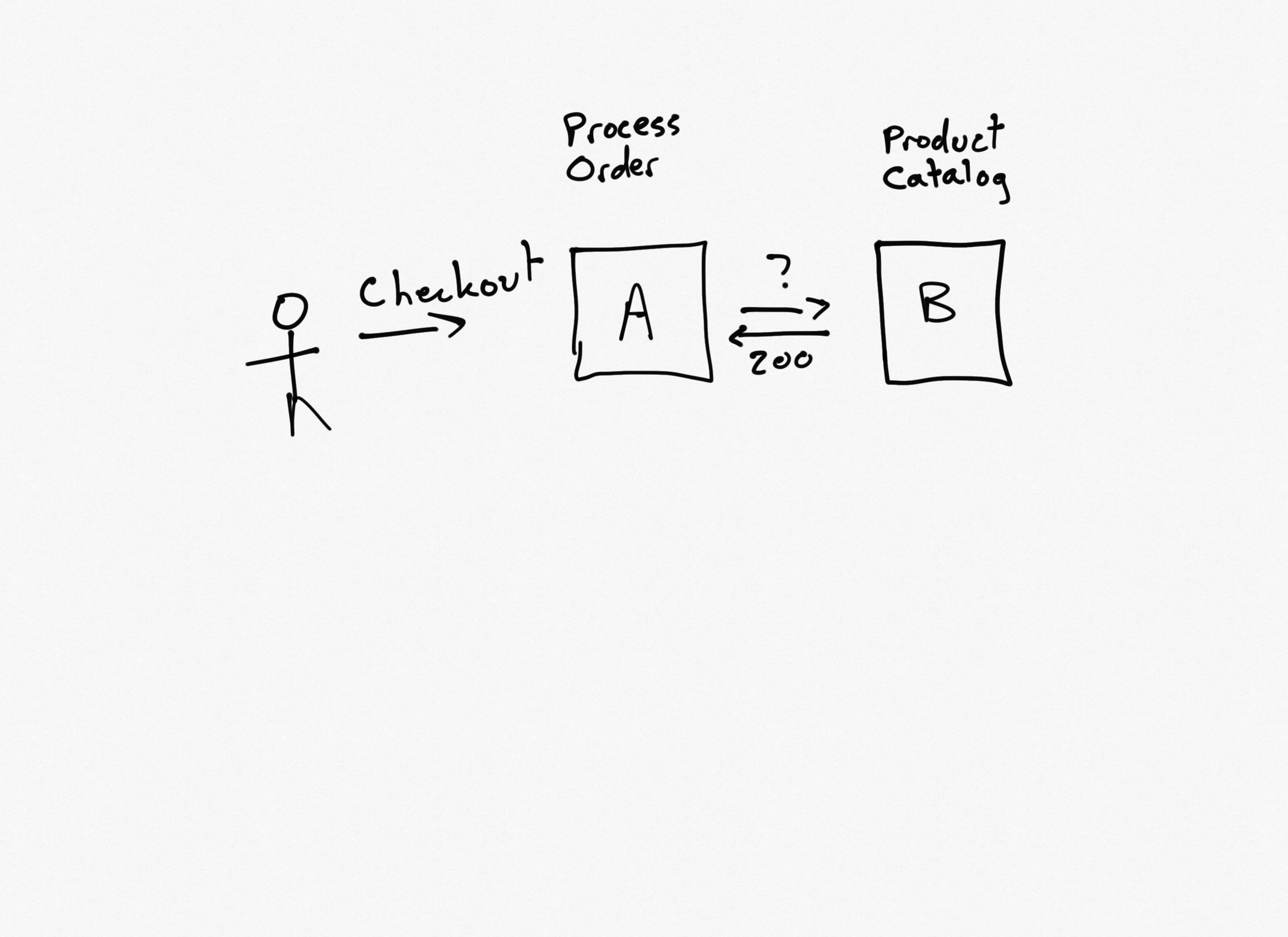

Direct API Call

When you need something from another service, sometimes the easiest way to get it is just to ask. In this case, the order processing service (A) can make a synchronous API call to the product catalog service (B). This requires that service A knows about service B, and that both services are available at the same time. However, it is a fairly straightforward approach that doesn't require any additional services or complexity like message queues or buses.

Performance

Performance of direct API calls depends heavily on the speed with which the call can be processed and completed. For lengthy requests, the synchronous nature of the call can harm the performance of upstream services (that is, service A's response time will take at least as long as service B's response time).

Scalability

Since both service A and B can scale out, this technique can scale up well as needed.

App Isolation

In the basic version of this approach, service A depends on service B. Any breaking change to the signature of service B will require an update to service A. Additionally, if service B's network location changes, A must be updated. These issues can be mitigated through the use of centralized configuration and/or gateway patterns. What cannot be as easily mitigated is the temporal dependency between the two services. If B is unavailable, A will also be unavailable.

Complexity

This solution tends to be more complex than the shared database, since multiple application processes are involved. Debugging and testing can be more difficult, and there are more ways in which the application can fail. However, overall this is a relatively simple approach.

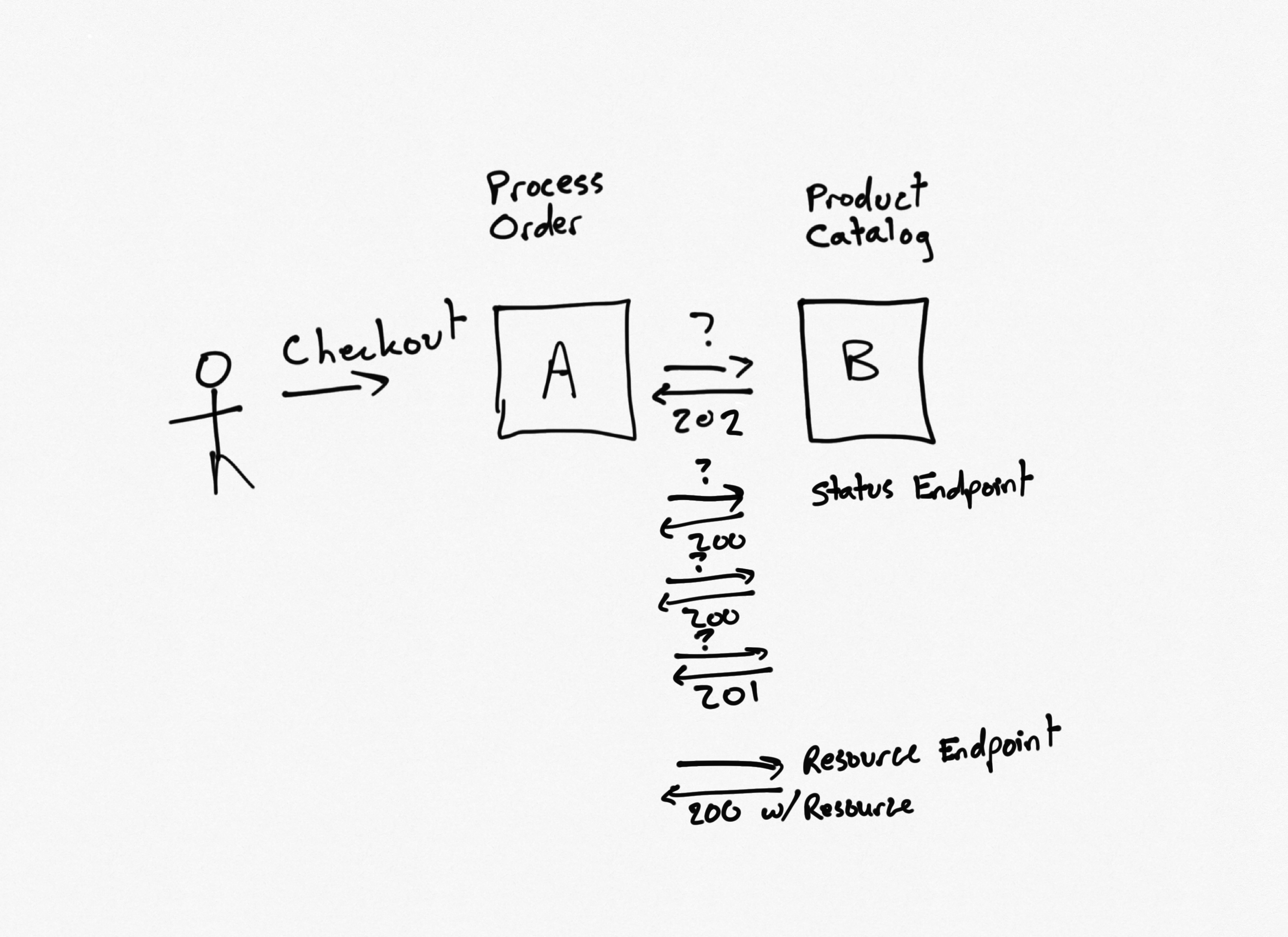

Direct API Call with Async Polling

For longer requests, an initial API call can complete quickly, but provide a location header indicating where to check on the status of the request. Subsequent calls to the status endpoint will (if successful) eventually result in the resource or result being requested.

In this example, for any request that cannot be completed quickly, service B can return a 202 with the location of the status endpoint. Service A can poll the status endpoint (additional headers might indicate how long to wait before checking the status again), eventually getting back the result it's expecting (or timing out or any number of other error states). Note that this pattern can be applied wholesale to all API calls, if desired, resulting in a consistent backend approach. However, more often it's added on an as needed basis to slow-performing endpoints. The pattern can also short-circuit, returning the resource directly if for instance the requested resource is already ready to go (such as available in a cache) rather than returning a 202 and forcing the caller to hit the status endpoint.

Performance

Solutions that involve polling and multiple requests will almost always have worse performance than those that simply make direct calls. Thus, this solution will incur a performance penalty due to the need for more web requests, as well as the additional wasted time that occurs between when the resource is ready and when the caller polls to get it. Shorter polling intervals will reduce the magnitude of this wasted time, but result in more overall load on the network and system.

Scalability

The scalability of both service A and B can be improved using this approach. Service A may be able to process more requests since it will have fewer outgoing requests blocked waiting for responses (though this is less of a factor with modern async patterns in HTTP client code). Service B can scale up to handle many more requests if it is able to offload processing to other resources and is only responsible for quickly returning 202 responses and then handling status checks. The actual work involved might be done by other processes that are not coupled to service B at all.

App Isolation

The app isolation assessment hasn't really changed from the direct API call. If anything, it's worse since in addition to the specific endpoint on service B needed to make the initial request, service A is now also dependent on the status endpoint and the polling pattern (headers, etc) employed by service B.

Complexity

This pattern adds to the existing complexity of a synchronous API call by adding additional endpoints and polling behavior.

Async Messaging Everywhere

Some applications take the approach of eliminating all synchronous calls between services, opting instead to use messages for everything. While asynchronous messages work well for publishing status events and issuing commands, they're more difficult to use with queries. Many architectures that leverage CQRS will use messaging systems for the Command part of the pattern, while leaving Queries as synchronous calls. This approach, however, issues queries as if they were asynchronous commands, and then either waits until the corresponding event indicating processing of the query has occurred or returns immediately and informs the client of the status of the query through other means when the response arrives.

(I need to draw this one still)

Imagine that service A needs to know the price of a product as part of the checkout process. So it sends a command, ConfirmProductPrice, via a message bus. The checkout request initiated by the end user then waits some period of time for the response to arrive as a message, or simply returns, indicating that the request is still in progress. When service B gets the command, it performs the query and publishes an event ProductPriceConfirmedEvent or similar, which service A consumes. The running checkout request can then return, or if it had already returned, the client can be updated through other means, such as web sockets or SignalR.

Performance

Messaging-based systems typically have worse performance for individual calls than direct, synchronous patterns. Additionally, the performance of individual requests can vary dramatically if a large number of requests have built up in the queue, since every request must now make it through the queue before it can even start to be processed.

Scalability

Async messaging-based systems tend to be extremely scalable, since any number of services can pick up the messages and process them independently of one another and of the requesting system. In addition, the use of a message bus to return responses further decouples the apps from one another, enabling easier scaling of the system.

App Isolation

A benefit of this approach is that services A and B have no direct dependency between them. They don't depend on one another's API definition or database schema (they do both depend on a common messaging schema, however). They don't need to be available at the same time. Service B can go down for short periods of time and Service A can continue working unimpeded.

Complexity

Asynchronous processing is inherently more complex than synchronous processing, and requiring every query in addition to every command to process asynchronously can result in a great deal more complexity. Diagnosing problems at runtime and debugging are both more difficult than with simpler systems, and typically will require more advanced logging and monitoring capabilities to enable better maintainability of these systems.

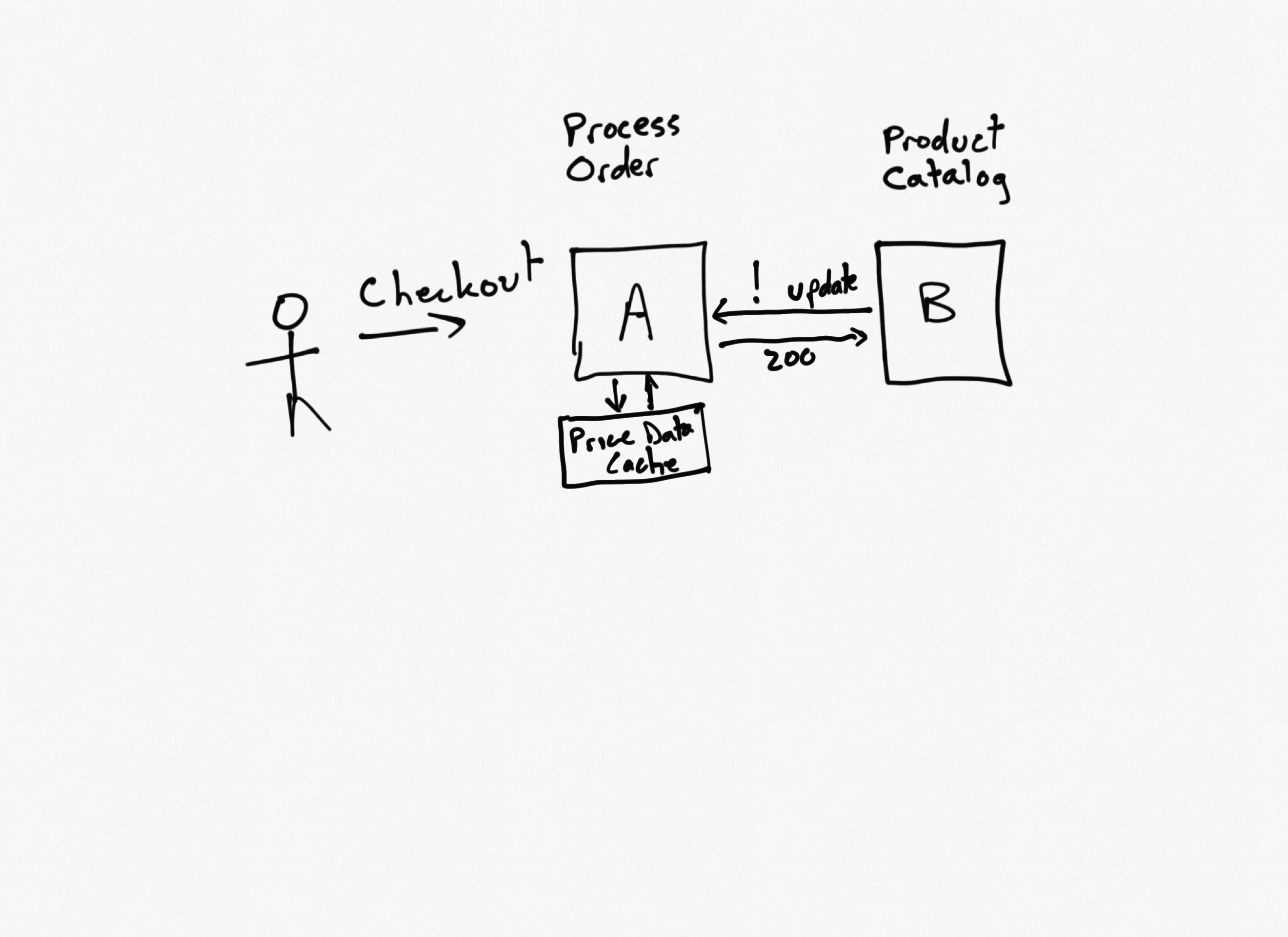

Local Cache with Direct API Updates from Source of Truth

The fastest call to another service is the one you don't have to make. Instead of making a call to another service every time you need a piece of information, especially something a service needs frequently, a local copy of the data can be stored in a cache. This can be an in-memory cache, or it can be a persistent store like Redis or even the same database the service uses for its own persistence needs.

Any time the needed data isn't found in the cache, it can be requested from the "source of truth" service using the Cache-Aside pattern. Cache entries often are given an expiration date, but in order to better improve runtime performance (and avoid having a client request pay the cost of updating the cache), the downstream service can make an API call to the consuming service to update its cached version of the data any time its data changes. In this way, the cache can be kept in sync with its source data without necessarily needing short expirations or frequent updates, at least for "read mostly" kinds of data.

In this example, service A will have a list of products and prices in its cache. Any time the pricing is updated, or new products are added, service B will call an API on service A (and any other subscribing services) to update it with the latest data.

Performance

By eliminating the need to call out to service B at runtime in the vast majority of situations, the performance of this approach exceeds the API and messaging-based communication approaches listed above (and is likely about the same as the shared database approach, but may be better since service A's database is unlikely to be impacted by load from other apps).

Scalability

The direct API calls to upstream consumers of service will only scale so far. If the updates are frequent and the number of subscribing apps is large, service B can quickly end up spending a lot of its time making inter-service calls to update other apps (which may or may not need such constant updates). However, for relatively small systems with relatively stable data, this approach works quite well.

App Isolation

This design uses a form of dependency inversion. Although service A depends on service B for its data, service A has no compile time or runtime dependency on service B (unless it uses the Cache-Aside pattern, which is optional). Instead, service B needs to know about service A and its API for processing updates to its data. It also requires service A to be available any time updates are made to its data, otherwise it will need retry logic to ensure eventual consistency or the system will need to resort to cache timeouts to ensure missed updates eventually are corrected.

Complexity

Service A's complexity is less than for most of the other approaches shown. Absent the Cache-Aside pattern, service A operates as if all of the data it needs is local to it in its own data store (though it should take care to only read, not update, this data). It does need to build and expose APIs to update the otherwise-read-only data, though, which service B will use when updates occur.

Service B is more complex, however, since it needs to perform whatever operations are its responsibility and then also handle updates to all subscribing services any time a change occurs that would impact those services' cached data. That can be more difficult than it might seem at first, since it's often not as simple as a straight 1:1 table mapping.

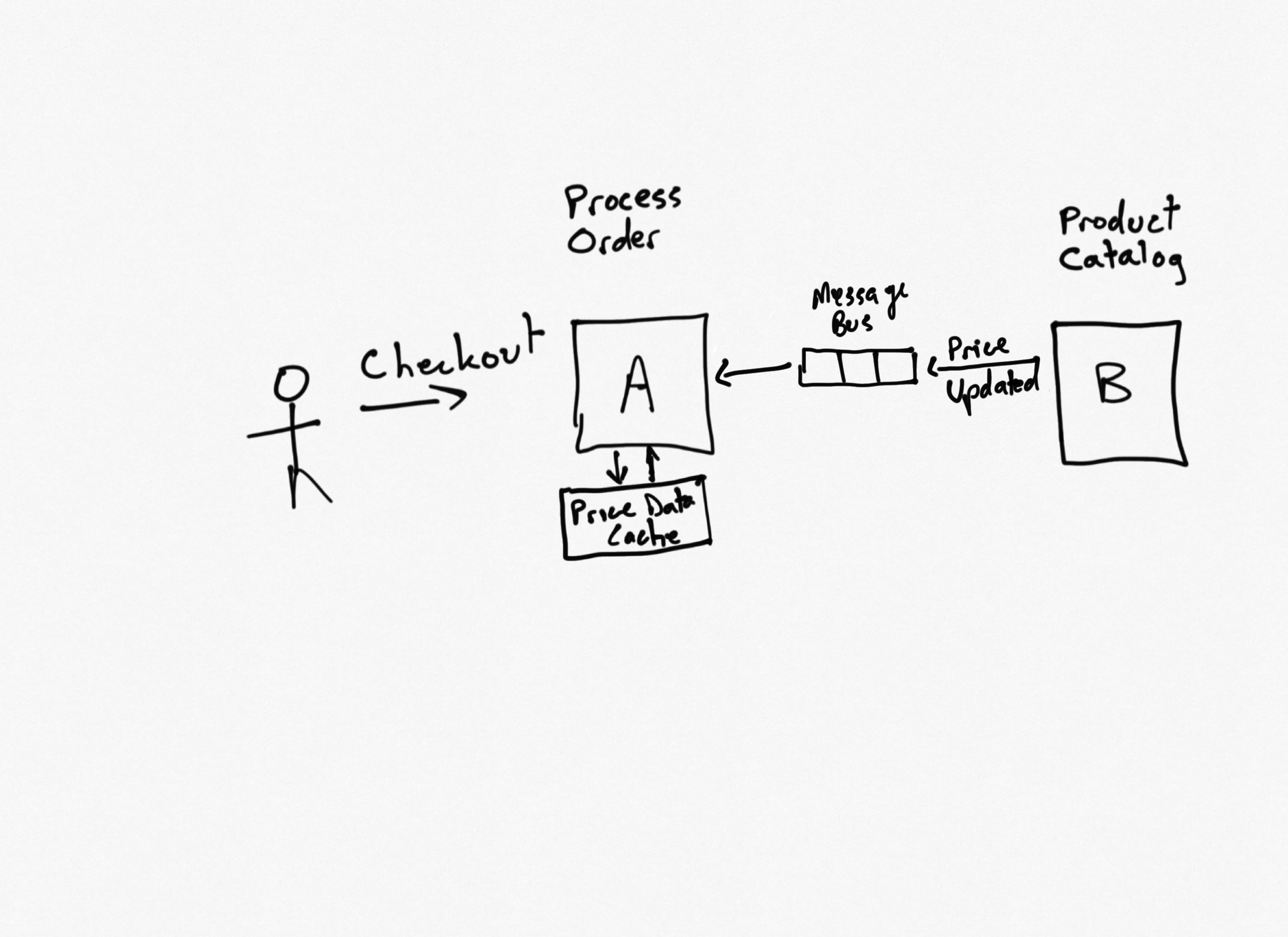

Local Cache with Update Events from Source of Truth

It's still going to be faster to already have the data than to have to go and get it. With this approach, the design is the same as the previous one, but instead of making API calls to update upstream services, the downstream service simply publishes events. This approach has all of the benefits of the previous approach, but dramatically simplifies the overall architecture. Instead of having to build and define and consume APIs, service A simply needs to handle certain kinds of events it's interested in, and service B simply needs to publish events when certain changes occur.

Performance

High, just like the previous one.

Scalability

Like all message-based systems, this one scales extremely well.

App Isolation

Service A can operate without service B. Service B can operate without service A. Neither depends on the other at runtime; both depend only on the format of the messages passed and the implementation details of the message bus used.

Complexity

This approach is more complex than just using a shared database, but service A is able to read data just as easily as it would in that scenario (possibly easier, since it has complete control over the structure of the data and isn't sharing that schema with any other service or app). However, service A needs to support message handlers to detect updates and apply them to its local store of the data. Service B simply needs to publish events when updates are made, which adds some complexity but is generally simpler than dealing with calls to multiple API endpoints on multiple apps, as the previous pattern required.

Mixing Methods

Consistency is valuable and can help reduce complexity in the system. However, you should sacrifice the user experience you need for the sake of complexity. If most of your system can use one technique, but a few services would benefit from using another approach, by all means use the right tool for the job. You can mix-and-match techniques however you see fit, but it's usually best to identify a class of services or behaviors for which a given technique is the best fit. Maybe reports that take a while to generate benefit from the API and polling technique. Maybe commands benefit from a purely-async message-passing approach, while queries use a more determinant flow. Inconsistency can be mitigated if there are established rules that can be followed so a new developer writing a new service can easily determine the appropriate pattern to employ. Tools like architecture decision records (ADRs) can be helpful for documenting and communicating such decisions and policies.

Summary

I typically try to avoid using a database as a method of inter-service or app communication. Instead, I've found message-based approaches to work quite well. For microservices and apps that require independence from one another, the last design shown often works quite well. It's not always possible to front load all of the data the app might need from another service, but you may be surprised to learn how often it is possible to do just that. In my 2021 DDD Fundamentals course on Pluralsight, the demo application I built features a vet clinic scheduling app as well as a clinic management app that's responsible for updating clinic details like doctors, appointment types, exam rooms, etc. This kind of read-mostly data I kept in the scheduling app as well, as a read-only cache of the data in the clinic management app. Whenever updates occurred, the clinic management app would publish events describing the changes, and the clinic scheduling app would handle the messages to updates its copy of the data.

That said, it's worth considering all of the various options you have for communication between services. Think about what will work best today, as well as how that might work in the future if you ramp up the number of API endpoints and/or apps and services by a factor of 5 or 10 or 100 (whatever you anticipate for your needs). Ship what you need today, but don't design yourself into a corner if you expect to need to shift approaches in the future.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.