Commands, Events, Versions, and Owners

Date Published: 04 May 2022

Commands and events are two common types of messages used in distributed application architectures, including microservice designs. Sometimes message formats need to be updated. Which party in the communication is responsible for the message definition? Who owns the message schema?

Let's look at an example.

Distributed Messages Example

Imagine you have a product catalog service. Other systems rely on this service. Much of its interaction with other systems uses asynchronous messages, in order to optimize the overall system's availability (see CAP Theorem, PACELC, and Microservices).

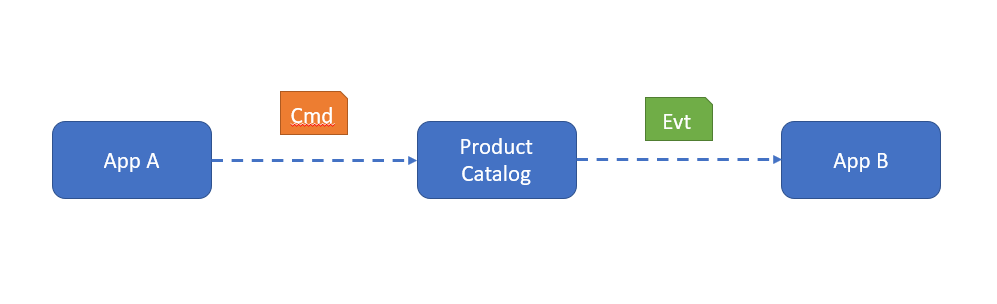

Another system, A, sends commands to the product catalog to update its list of available product categories. And a different system, B, subscribes to ProductAdded and ProductUpdated events that the catalog publishes when changes are made to it. The overall design looks something like this:

In each of these cases, the contract representing the message - the command or event - must be shared between both ends of the communication channel. There are many ways this can be done: shared library, NuGet package, or even just copy-paste. But if an update is necessary, it needs to be done on one end, and then the other, before any new feature of the message can be shared between two ends of the communication.

NOTE: For the purposes of this scenario, each of these applications is its own bounded context. The command being sent to the catalog is impacting its domain model, not necessarily any shared data. Applications A and B do not have direct access to the catalog via a database or similar "back door", but rely on communication channels the catalog provides.

The question is, who owns the contract? Who is responsible for choosing when and how to change the message format, including breaking changes?

Ownership of Contracts

In simple architectures for smaller applications or smaller organizations, often the same team is responsible for both sides of the communication. Initially the team may have built a monolith, and later they restructured it into a distributed system, adding appropriate messaging constructs along the way. As long as that same team continues to control both ends of the communication channel for every message interaction, there's not really anything to worry about here. The single team is responsible for the entire system, the senders and receivers, and the messages they use.

However, things get more complicated when there are more teams and more systems involved. In the simple example above, it may not be clear who should own changes to the messaging formats, or why it even matters. If it is all one team, they can just make all the updates at once. But let's assume for a moment that there are three separate teams, one for the product catalog and one for each of the other applications.

If a change to Application A's command to add another product category is required, which team should control this change? Team A or Team Catalog?

If a change to the event Application B consumes when products are updated is required, which team should control this change? Team B or Team Catalog?

What do you think? Stop reading for a moment and think about it.

...

Can we come up with a rule that applies universally? Should the sender always control the message contract? The receiver? Sometimes it helps if you take a moment to consider a more complex system with more components interacting.

Messaging Contracts for More Complex Systems

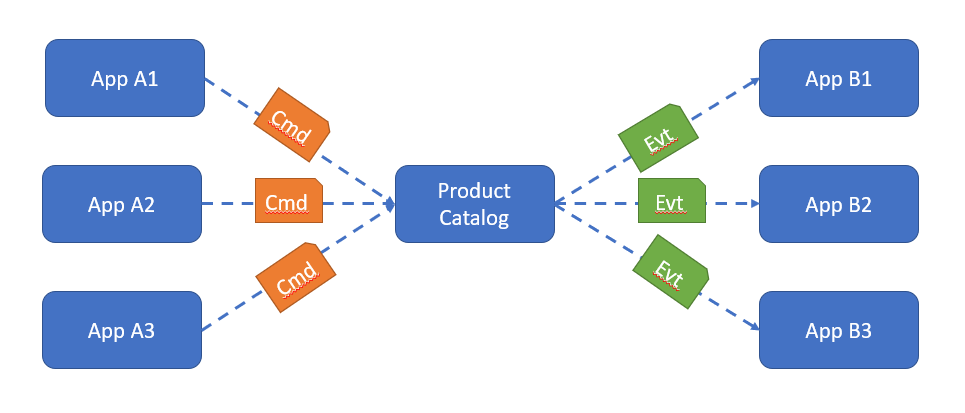

Imagine that application A isn't the only one that can send commands to the product catalog - any number of applications might choose to do so. And likewise, when the catalog publishes events, any number of downstream applications may care about and thus subscribe to those events. The resulting architecture starts to look more like this:

When each communication channel is one-to-one, or when the team owns both ends of the channel as well as the message format, it's more difficult to reason about who should be responsible for the message contract. But once you add more connections, it becomes easier to make such decisions. Another thought exercise that helps is if you imagine that some of the clients of the messaging contracts are external, not other members of your team or even your company.

In the above diagram, imagine that A1 is an application one of your company's partners built, and B3 is an open source community tool.

Given all of the above, who should own commands and events? Is it the sender, the receiver, or something else? Then answer is: something else.

Handlers own Commands, Senders own Events

In the diagram above, you can see multiple applications sending commands to the catalog, and multiple applications receiving its events. What you don't see, and what wouldn't make sense, is multiple different applications getting commands to update the product catalog's internal list of product catagories. Nor do you see multiple applications publishing events noting that a new item is available in the product catalog. There are one-to-many relationships involved in both of these operations.

Command messages involve one handler, many potential senders.

Event messages involve one sender, many potential recipients.

The owner of the contract is the end of the communication channel that has one, not the side that has many.

Why?

It wouldn't make sense to have any one of dozens of consumers of a message to control its format. Especially when some of the many consumers might not even be a part of the organization that controls the other end of the contract.

Why does this matter

Why does it matter who is responsible for the messages?

As more and more systems move to the cloud and toward event-drive architectures, teams will need to deal with how they version and share messaging contracts. When systems are small, it's often not obvious to developers who should be responsible for the contract, which can lead to early decisions about how to distribute the messages that cause problems later.

If you're building a distributed system that uses messages - commands and/or events - to communicate between different applications or microservices, you should plan for how the contracts of those messages will be shared and versioned (NuGet packages are often a good choice). And, given the information above, you should identify the team and/or application that is responsible for the messaging contracts.

Summary

Distributed systems communicate using messages that must have a shared structure. When that shared structure needs to be updated, it only makes sense for one side of the communication channel to be responsible for updates. In small systems with one-to-one communication this may not be obvious or important, but as systems and their numbers of collaborators grow, it becomes increasingly necessary to have a strategy for sharing this information in a consistent manner.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.