CAP Theorem, PACELC, and Microservices

Date Published: 17 November 2020

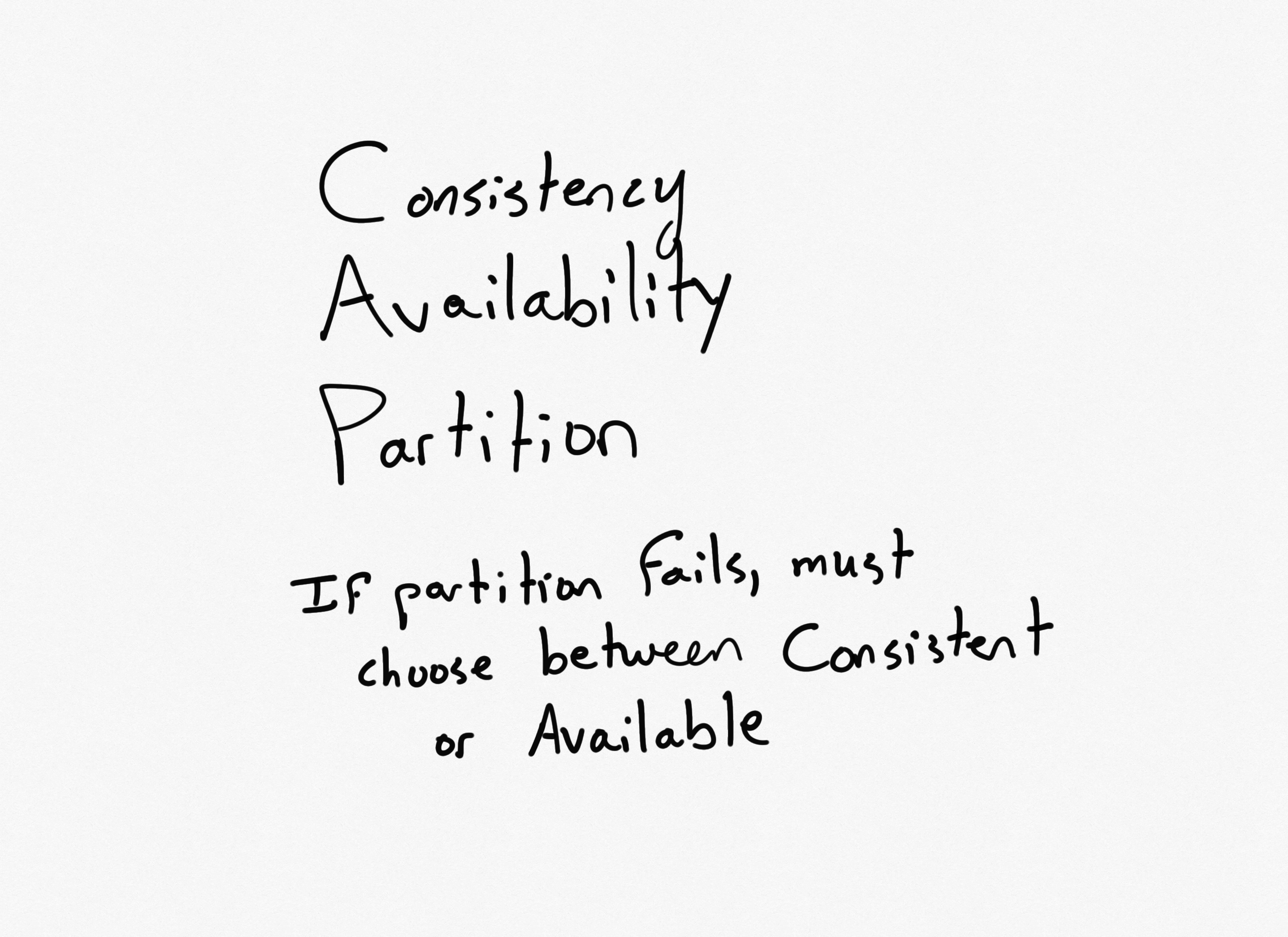

CAP Theorem (wikipedia) is a classic "given 3 choices, choose 2" topic. The three choices are Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance. You can't have all three.

Given distributed data or systems, the choice mostly comes up when there is a network partition, meaning two nodes of the system can't communicate immediately with one another. At that point there is a partition, and your architectural choices will dictate whether your system now can be Consistent or Available (but not both). We'll see why this is the case in a moment, but there's a corollary to CAP Theorem, PACELC (wikipedia).

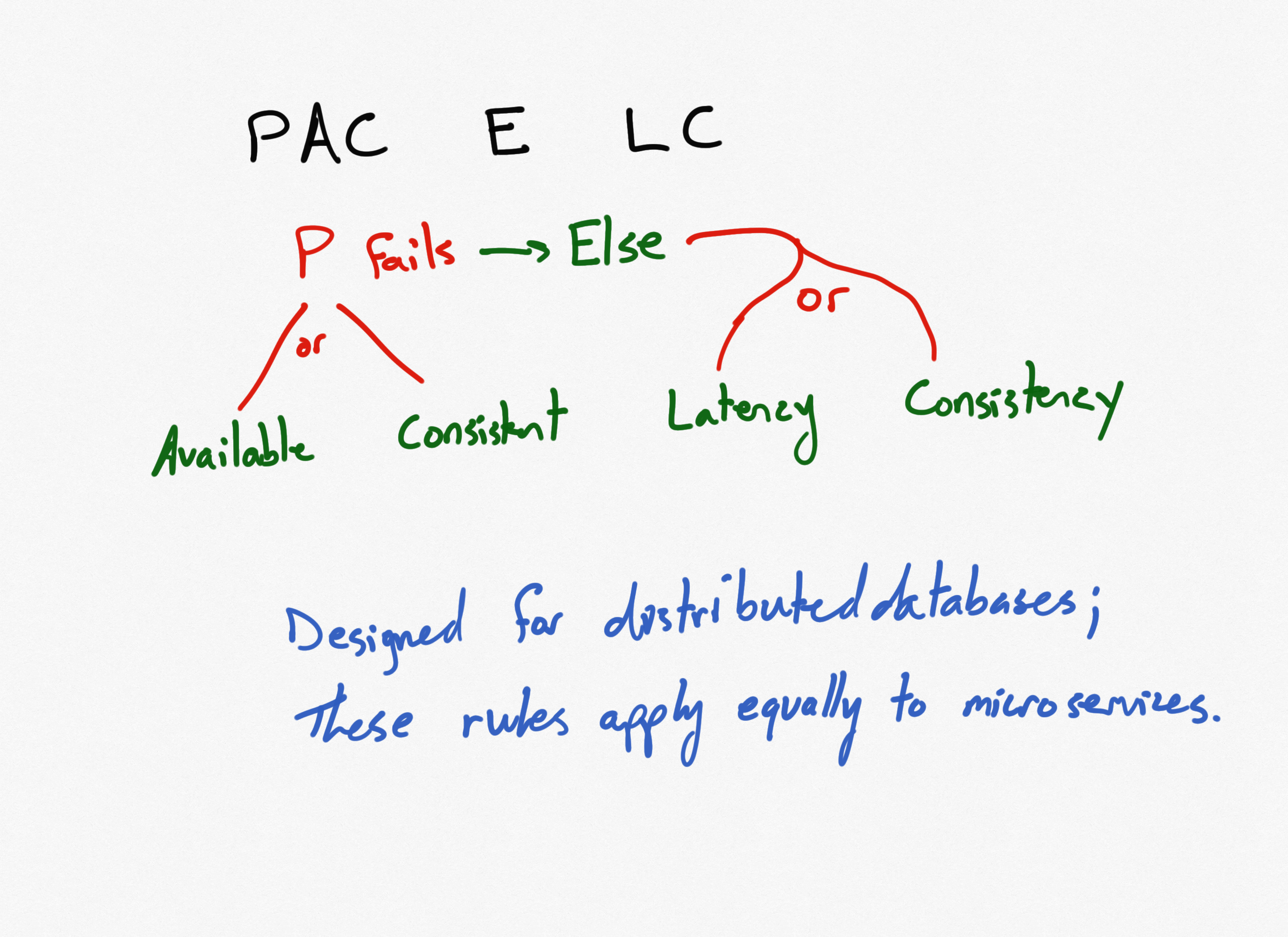

PACELC reorders CAP into PAC and adds a statement about what happens when the network is present. That is, you may choose between increased latency and consistency (Else Latency or Consistency).

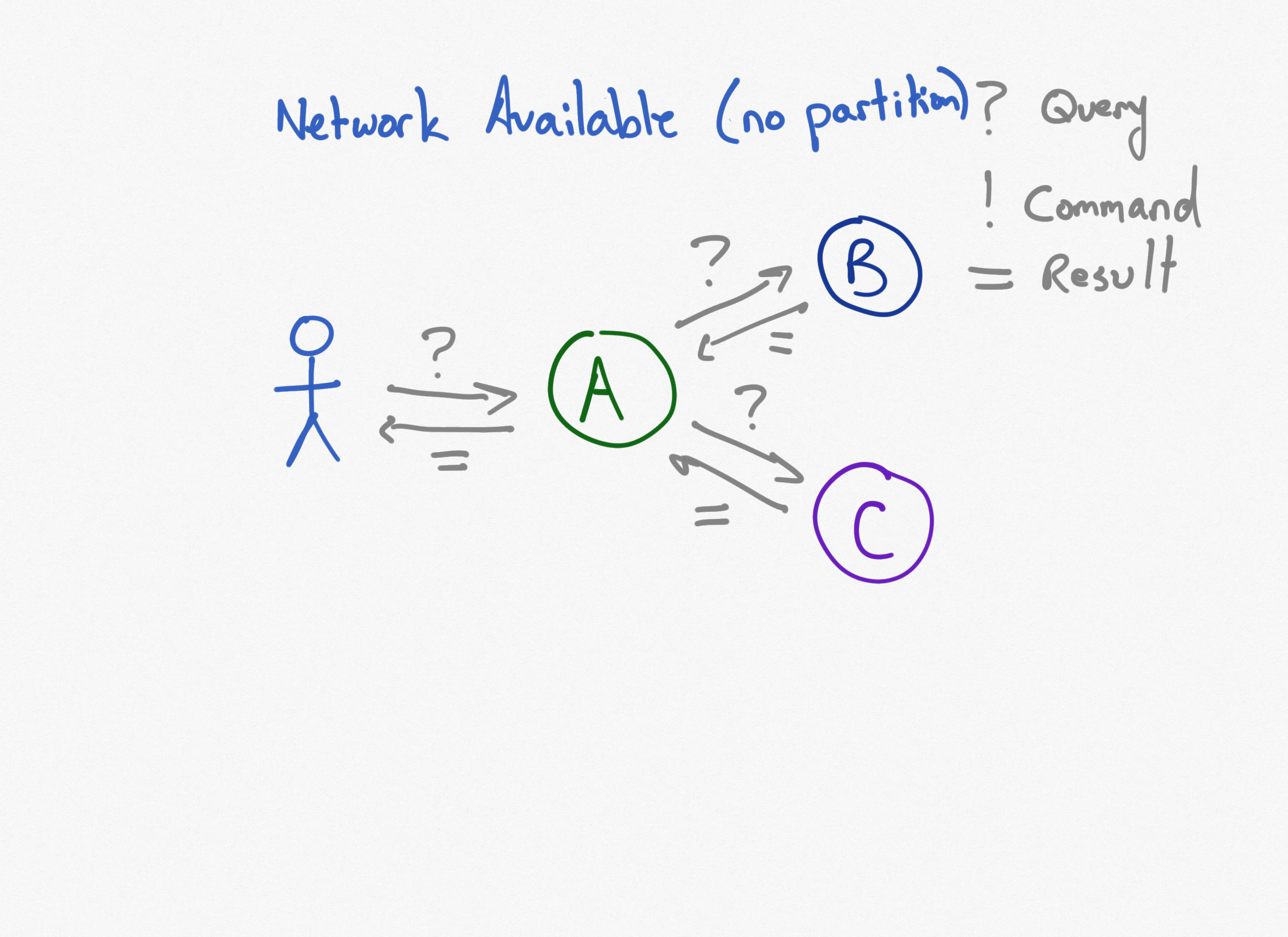

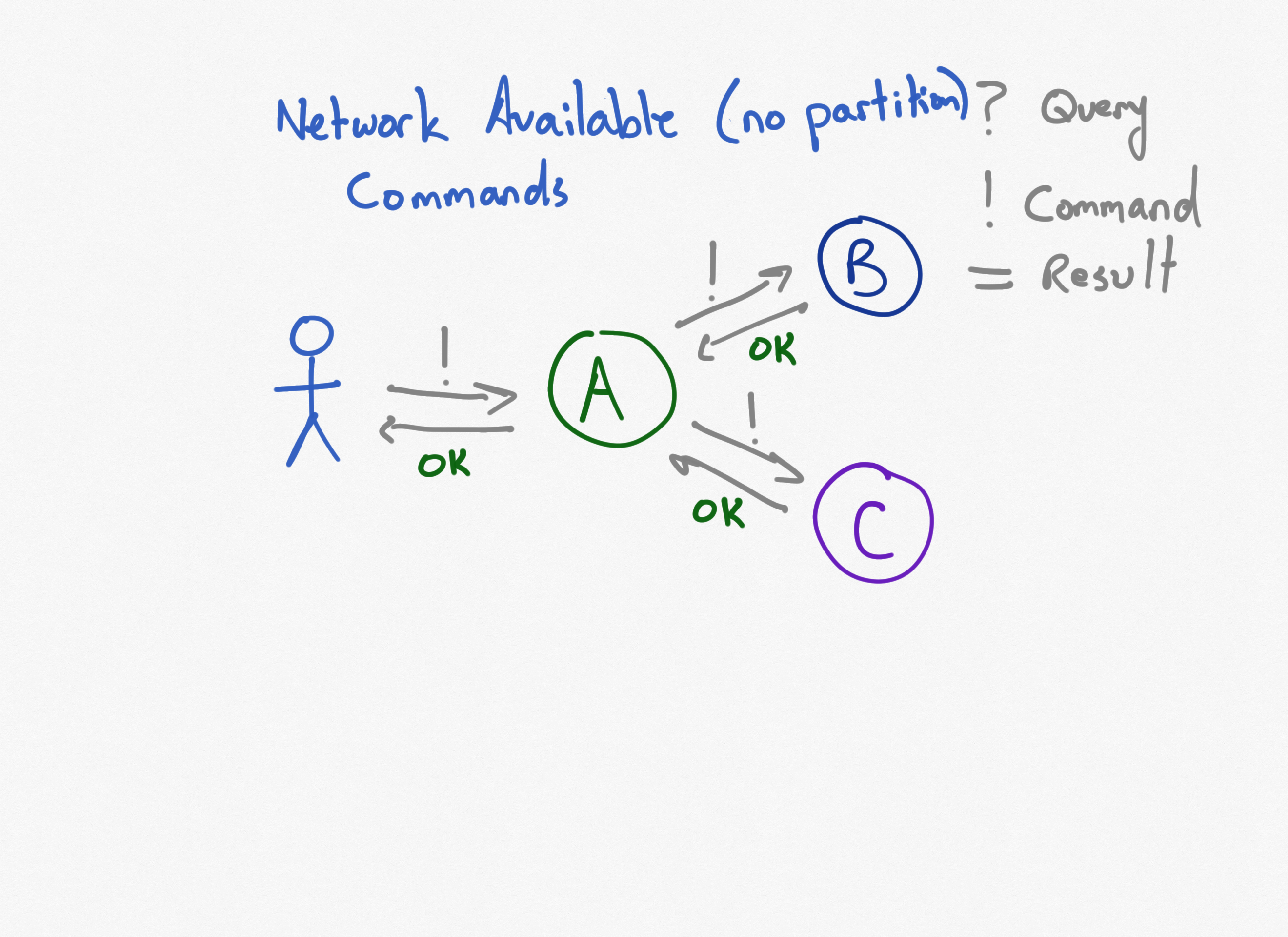

Now let's think about how this applies to microservices. For the purposes of these examples we'll also assume that the microservices are following Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS). The diagrams model queries with '?' and commands with '!'. Queries return results designated by '='. Commands don't return anything, they will just have a status code associated with them, like 'OK'.

Three Services with Queries and No Partition

In this first diagram, a user issues a query to a client-facing microservice (A) which in turn makes queries to two dependent microservices (B) and (C). The original service aggregates and returns a result.

With no partition, this system is available and consistent. It has minimal latency (aside from the latency resulting from the system being composed of separate microservices instead of a single app). But what happens when the network fails?

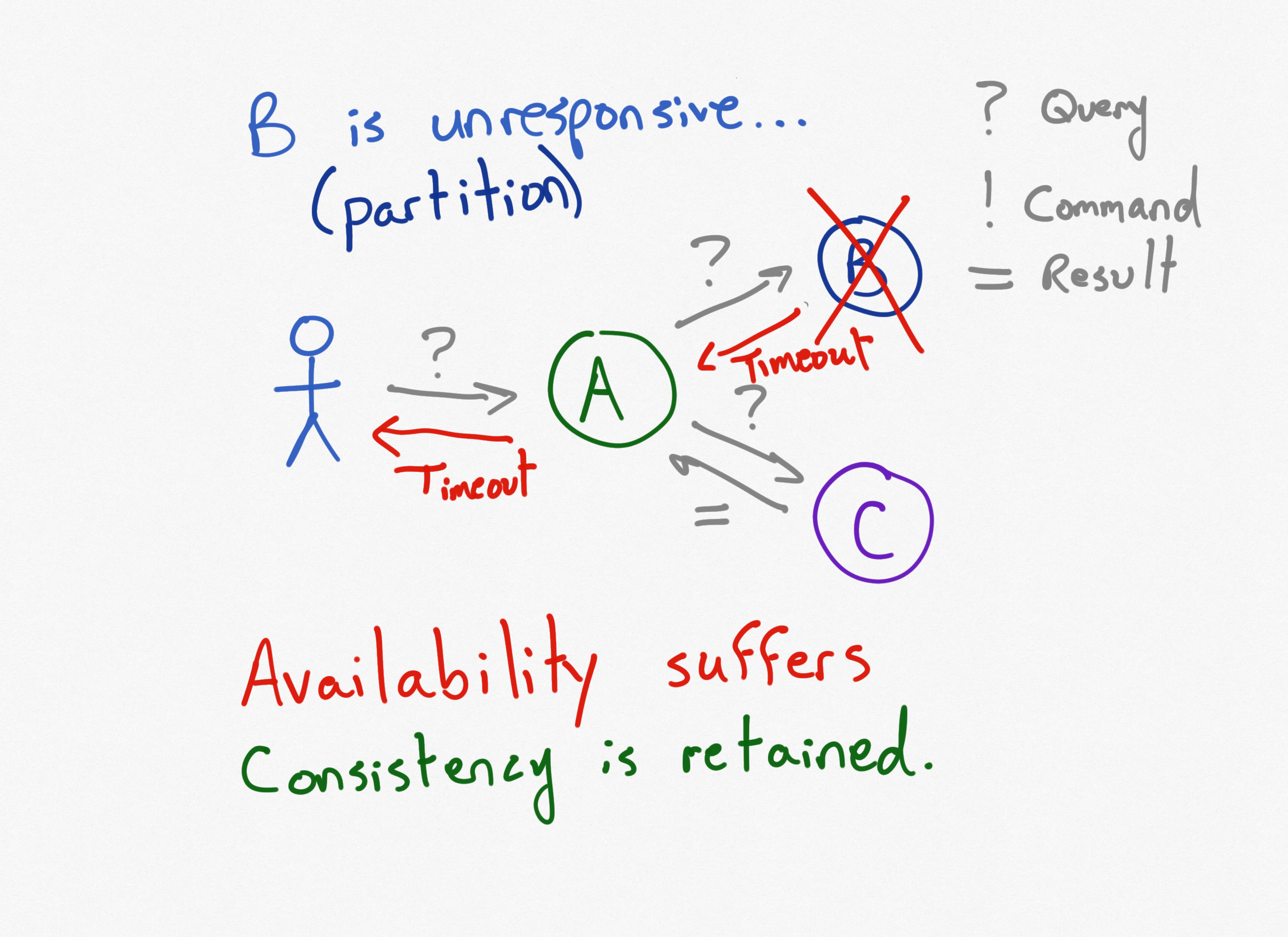

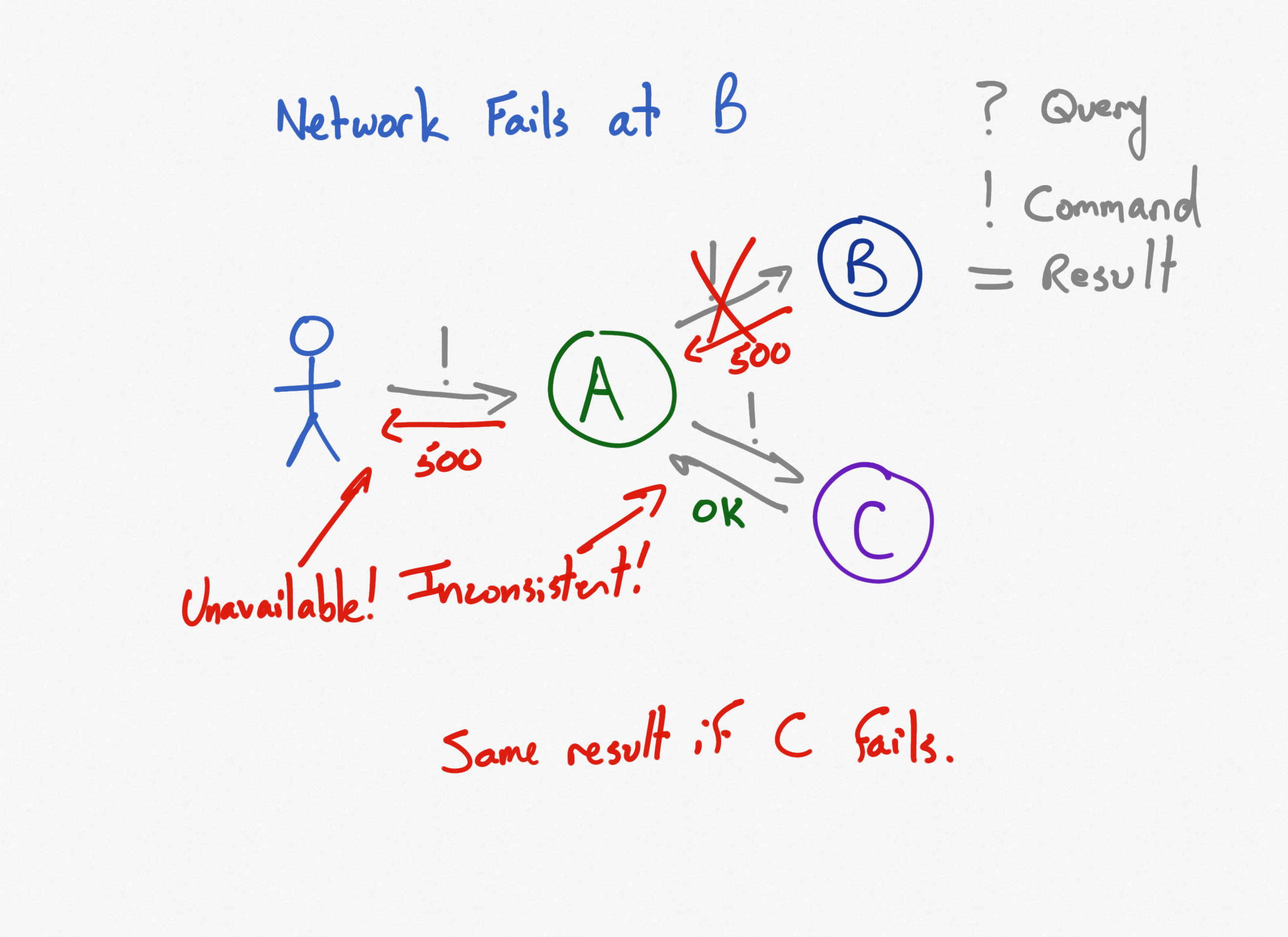

Three Services, Using Queries, Service B is Disconnected

The connection to B is severed through some failure. Maybe a router failed; maybe someone unplugged a network cable. Now requests made to service A, which depend on a query made to B, will time out and eventually fail. In the face of a network partition, the system no longer has availability.

Consistency is retained, though. Imagine that service B is still up and running, but simply cannot communicate with A. Data on B may be changing. If A were to try and return results that depend on B, without the latest updates to B, they would be inconsistent with the data in B.

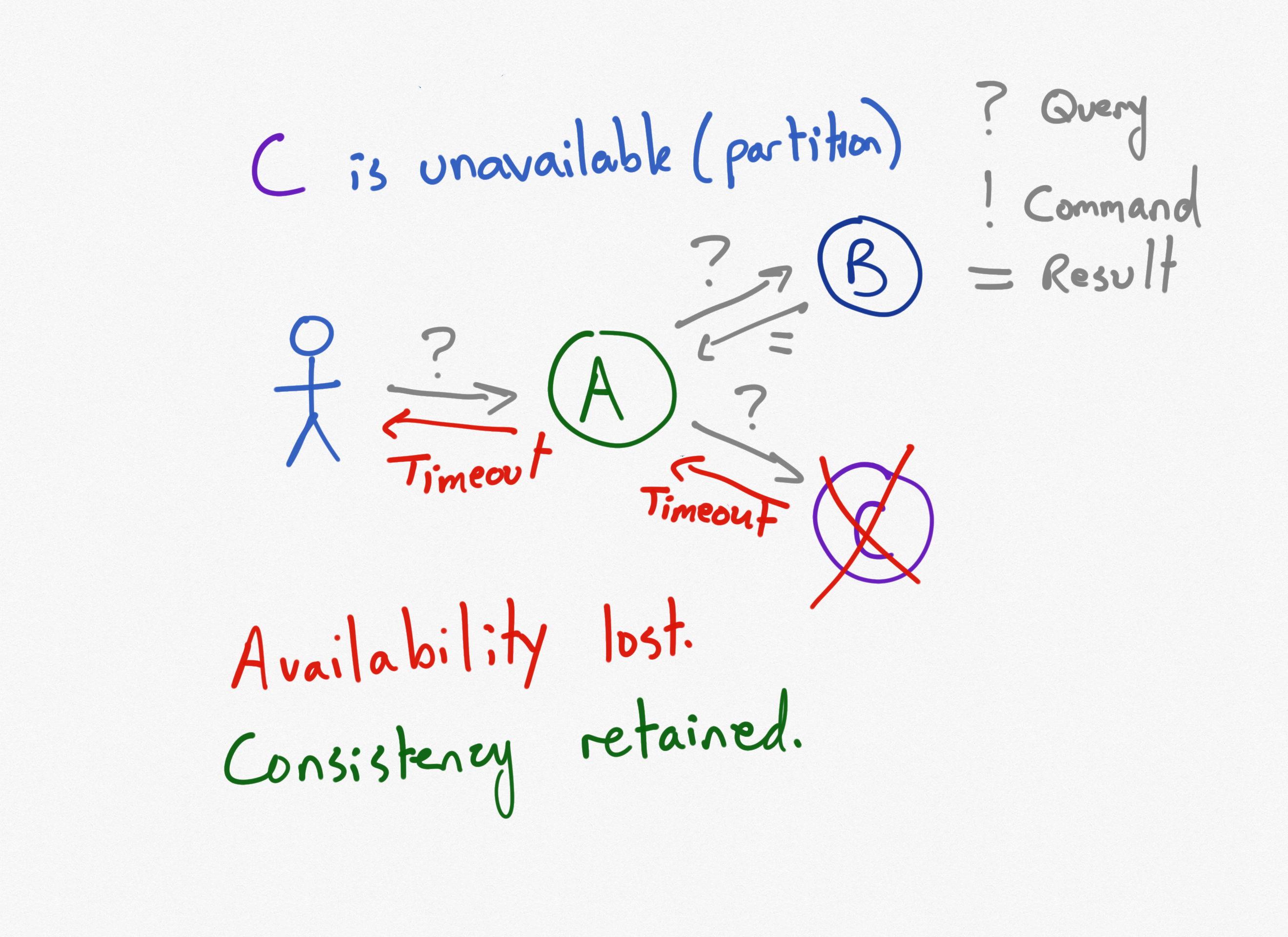

Three Services, Using Queries, Service C is Disconnected

Of course, the same thing happens if Service C is disconnected.

Service A is no longer available since it depends on service C.

In these scenarios, making direct, synchronous calls to dependent microservices is making an architectural decision that follows CAP Theorem. Specifically, this architectural choice is prioritizing consistency over availability. If instead we wanted to prioritize availability, how would this design change?

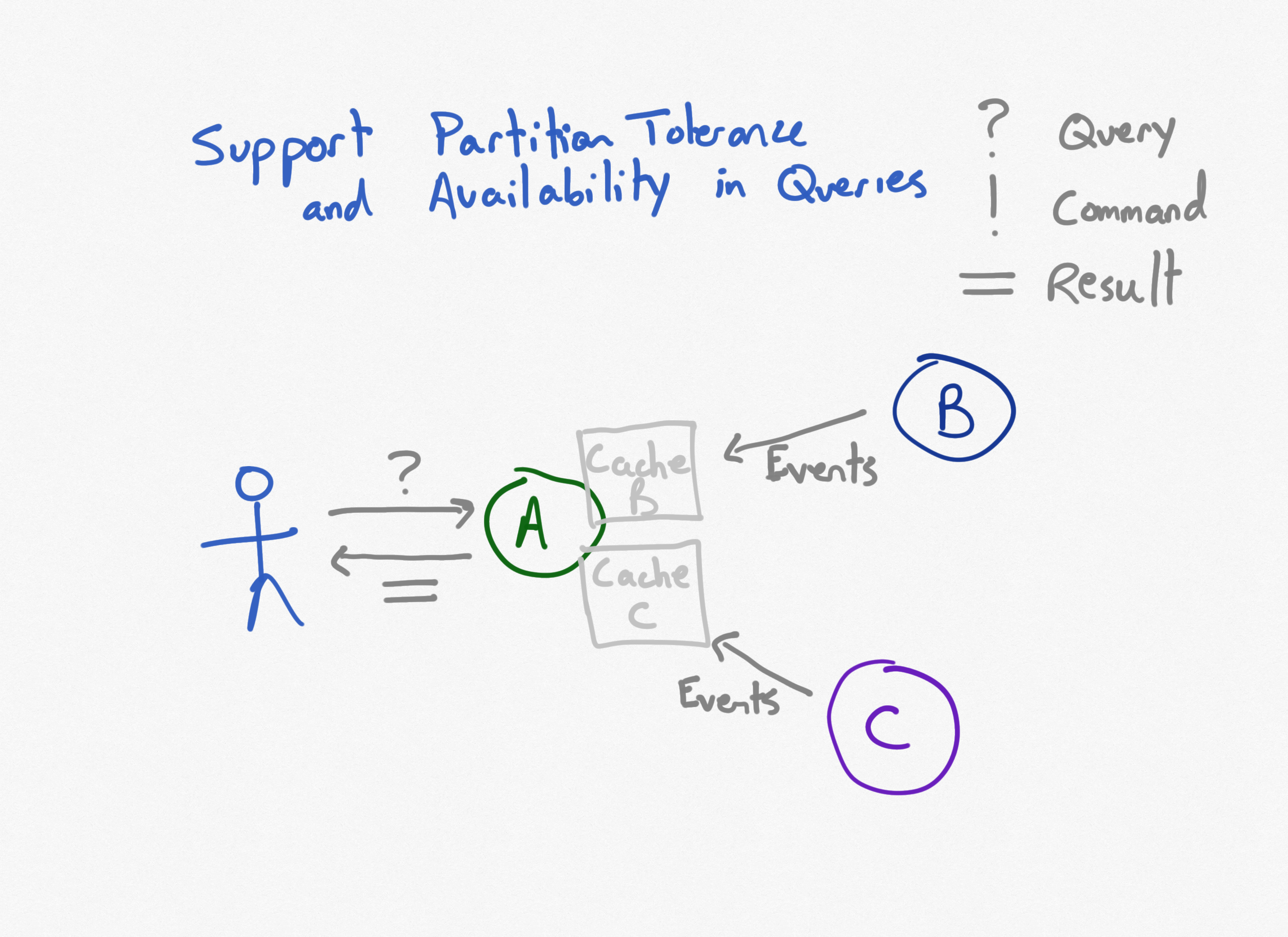

Three Services, Prioritize Availability

Given three services as before, if we want to ensure service A remains available even if it loses connectivity with either B or C (or both), a typical way to achieve this is to replace the direct, synchronous calls to the other services with calls to a local cache.

Any time data on B is updated, it will raise events that will update cache entries held within service A.

Any time data on C is updated, it raises events that update cache entries held within service A as well.

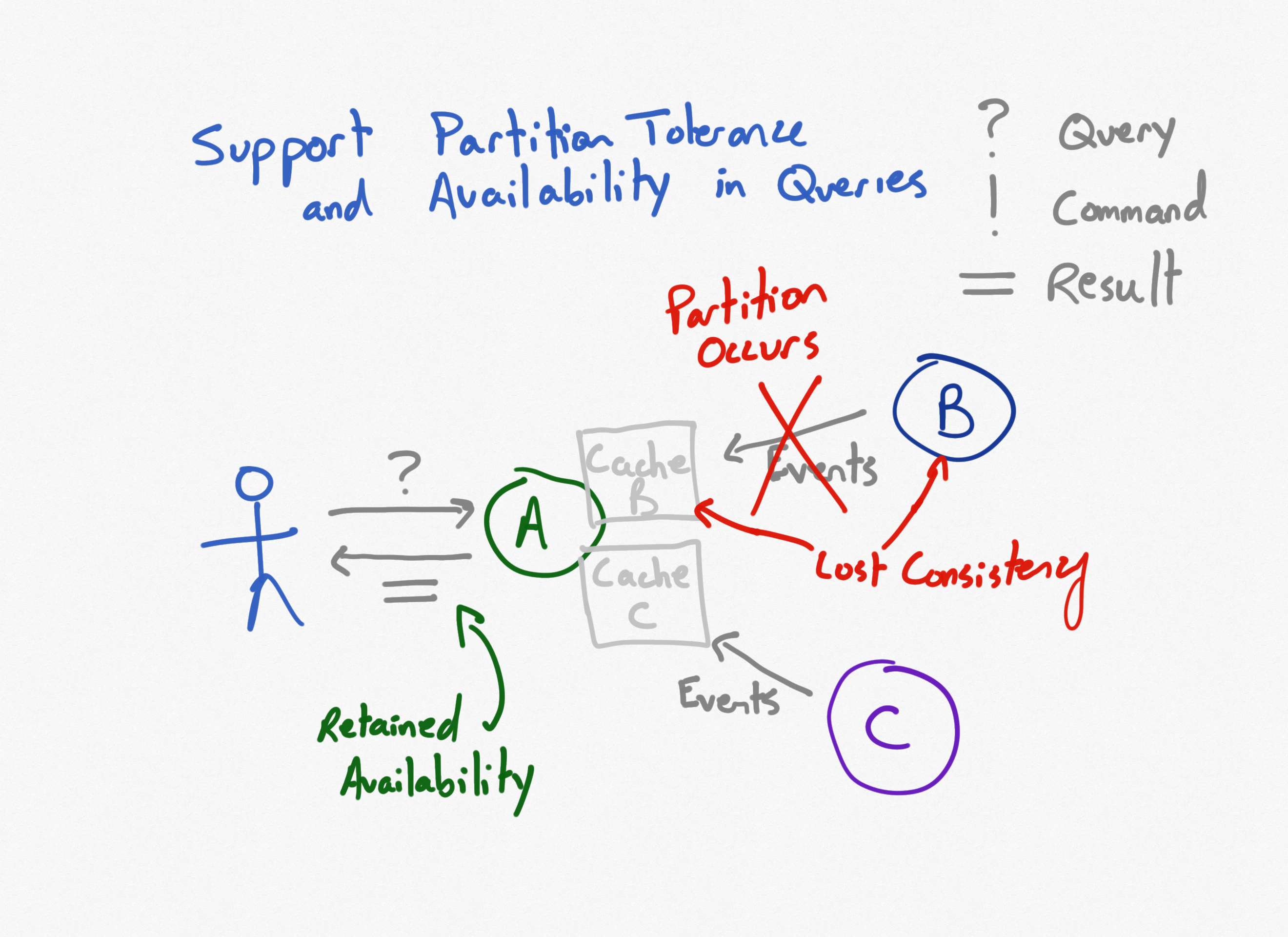

When everything is working properly, this system will have slightly higher latency than the previous design (as PACELC suggests). When a network partition is introduced, however, service A will remain available.

However, as changes take place in the dependent systems, the cached data used by service A will be inconsistent with its source data. At least until the network is restored, at which point, eventually, the systems should once more be consistent.

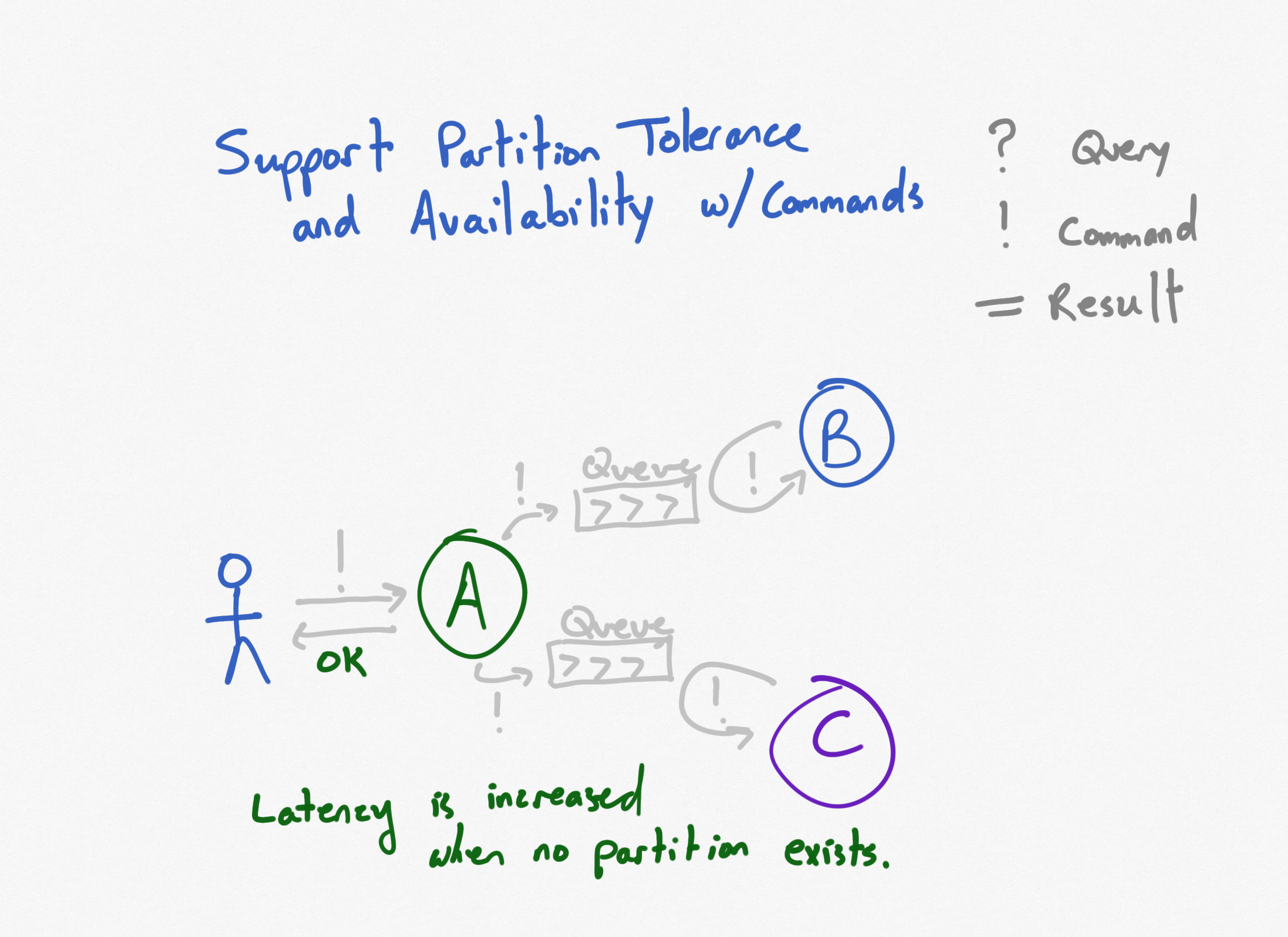

Three Services Using Commands

We've seen how to address network partitions with queries, but what about commands? The architectural pattern of caching which works well to deal with queries doesn't make sense with commands. We'll need a different approach, but first let's see what happens with direct, synchronous calls.

In this scenario, a command is issued to service A, which in turn sends commands to services B and C. When everything is up and working correctly, everything is fine.

Three Services, Using Commands, Service B is Disconnected

What happens in this scenario when Service B (or C) is disconnected? The command sent to it results in a non-OK status code. This should typically result in a non-OK status code being returned from service A, since it was unable to complete the command that was sent to it.

In this example, loss of network connectivity has eliminated the availability of service A. But even worse, it's also destroyed the system's consistency, since the command to service C went through! Now the system is in an inconsistent state and steps must be taken to recover from it, which may be expensive. One solution to this problem is to enlist all of the operations in a distributed transaction coordinator (DTC), but using a DTC introduces another point of failure and generally has very negative impacts on performance, so it's a heavyweight solution that should only be used if absolutely necessary. Fortunately, there are other patterns that can be applied.

Three Services, Commands and Queues

What if instead of actually calling the dependent services and waiting to see if they're successful, service A just queues up the commands in local persistent message queues? The downstream services then read from these queues over the network. This increases latency when the network is operational, and sometimes if the queues get long there could be significant latency between service A being called and all of its downstream commands being applied. But queue length can also be used as a signal to indicate whether additional instances of downstream services should be spun up, providing elastic scale.

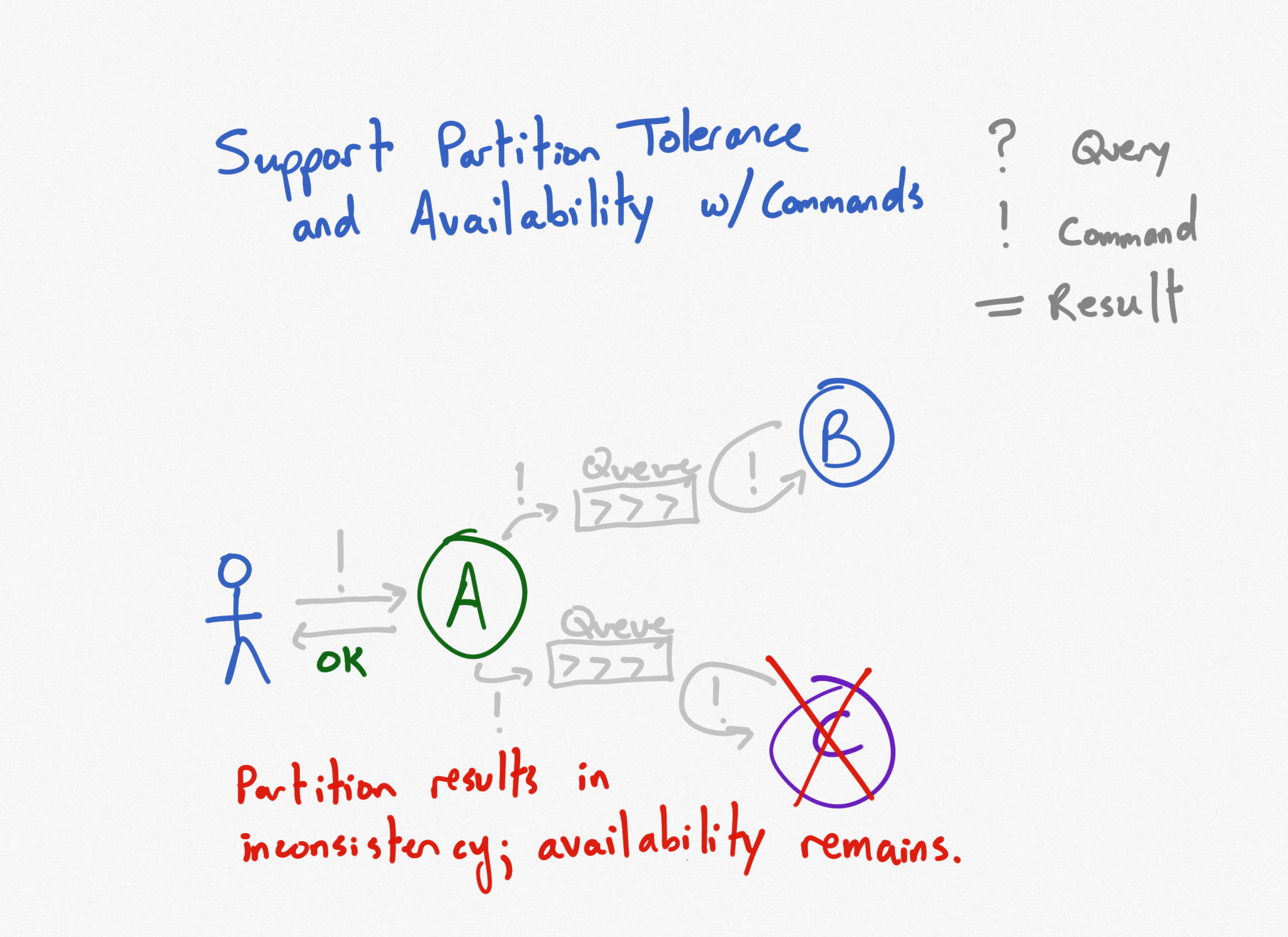

Three Services, Commands and Queues, Service C is Disconnected

What happens when one of the downstream services disconnects from the network, and is unable to read from its queue?

Service A remains available, and blissfully unaware that anything is happening with service C. Likewise, clients of service A have no indication anything is amiss. Availability is preserved. However, while service C remains disconnected and commands remained queued up but not processed, the system is in an inconsistent state. The higher order command represented by service A has ostensibly been completed, but only some of its dependent commands have been processed. Eventually, if service C regains access to its queue and successfully processes the backlog of commands, consistency will return.

User experience

These architectural decisions have impacts that extend beyond data centers and cloud providers. They impact how users interact with the system and what their expectations are. It's important in a system that is eventually consistent that users understand that when they issue a command and get a response, that doesn't necessarily mean their command completed, but rather that their command was received and is being processed. User interfaces should be constructed to set user expectations accordingly.

For example, when you place an order from Amazon, you don't immediately get a response in your browser indicating the status of your order. The server doesn't process your order, charge your card, or check inventory. It simply returns letting you know you've successfully checked out. Meanwhile, a workflow has been kicked off in the form of a command that has been queued up. Other processes interact with the newly placed order, performing the necessary steps. At some point the order actually is processed, and yet another service sends an email confirming your order. This is the out-of-band response the server sends you, not through your browser, synchronously, but via email, eventually. And if there is a problem with your order, the service that checked out your cart on the web site doesn't deal with it. Instead, you get a different email informing you of the problem and providing you with instructions to resolve it. And as an Amazon customer, you're accustomed to this workflow. You don't even think about it. Your customers, if they're familiar with Amazon, could come to expect similar workflows from your apps as well, if it makes sense for your system.

Conclusion

Architects constructing microservices must be familiar with CAP theorem, otherwise they will fall prey to its constraints by accident rather than by design. By understanding CAP theorem, educated decisions can be made to determine whether consistency or availability should be prioritized when (not if) there are communication failures between services.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.