Favor Privileges over Role Checks

Date Published: 02 June 2012

A very common practice in web applications, especially those written using the ASP.NET built-in Role provider (circa ASP.NET 2.0 / 2005), is to perform role checks throughout the code to determine whether a user should have access to a particular page or control or command. For instance, you might see something like this:

if (CurrentUser.IsInRole(Roles.Administrators) ||

CurrentUser.IsInRole(Roles.SalesAgents))

{

SomeSpecialControl.Visible = true;

}The problems with the maintainability of this approach become apparent after a short while. For one, any buttons or other controls on the SomeSpecialControl above that post back to the page should also do a role check to ensure the user submitting the postback is in an acceptable role, otherwise a security hole may be present and users outside of these roles may be able to perform privileged actions.

The other issue occurs if the number of roles changes at some point. As an organization and/or application grows and matures, it may require more fine-grained roles. For instance, an application might start out with just one role, Admins, that can do anything. As the application grows, additional roles may be added (e.g. Managers, Editors, Authors, etc.). Each time a new role is introduced, every if() statement like the one above needs to be re-inspected to see how the new role fits into its logic. In addition, controls like the LoginView control must also be checked, as well as an <location> sections in the web.config that depend on Roles to allow/deny access. In short, basing authorization directly on roles is a maintenance nightmare over time because it doesn’t follow the Open/Closed Principle nor the Don’t Repeat Yourself principle. It’s too low of an abstraction, in most cases.

Introducing Privileges

Operating systems have had the notion of privileges as a separate concept from roles for quite some time. This isn’t a novel idea, but it isn’t one I have seen commonly applied to web-based applications that require any amount of fine-grained authorization. By creating privileges as first-class concepts within your application, you make it much easier to manage future changes to which users should be granted such privileges. You also eliminate problems with a purely-role-based approach, such as privileges that apply to only certain resources. For instance, you might have a business rule allowing Authors to edit their own Articles but not other Authors’ articles. Editors, however, can edit any Article. Applying this logic with Roles will be simple for the editor, but rather messy for an Author, and most likely you will need to duplicate the required logic in a number of locations.

A privilege is always tied to a User or other actor within your system. You might opt to implement privilege support through the use of extension methods on your User class, though there are certainly other approaches you might take. With the extension method approach, you might write code like this:

EditorPanel.Visibility = CurrentUser.CanEdit(CurrentArticle);This is very clear and is at the appropriate level of abstraction. CanEdit isn’t itself a privilege; we can look at it as a sort of helper method in this case that lets us write clear and concise code. The privilege itself might be defined like so:

public abstract class Privilege<T>

{

public abstract bool CanCreate(T item, User user);

public abstract bool CanEdit(T item, User user);

}

public class ArticlePrivilege : Privilege<Article>

{

public override bool CanCreate(Article item, User user)

{

return user.IsInRole(Roles.Authors);

}

public override bool CanEdit(Article item, User user)

{

if (user.IsInRole(Roles.Editors))

{

return true;

}

if (item.Author == user)

{

return true;

}

return false;

}

}Using this design, it’s very simple to add additional checks to either the base Privilege

Without getting into extension methods just now, it’s possible to write unit tests that prove the expected behavior is present like so:

[TestMethod]

public void BeAbleToCreateArticles()

{

var priv = new ArticlePrivilege();

bool result = priv.CanCreate(new Article(), _author);

Assert.IsTrue(result, "Should be able to create a new article.");

}

[TestMethod]

public void BeAbleToEditTheirOwnArticles()

{

var priv = new ArticlePrivilege();

var myArticle = new Article();

myArticle.Author = _author;

bool result = priv.CanEdit(myArticle, _author);

Assert.IsTrue(result, "Should have access to own article.");

}

[TestMethod]

public void NotBeAbleToEditOtherAuthorsArticles()

{

var priv = new ArticlePrivilege();

var anotherArticle = new Article();

anotherArticle.Author = new User();

bool result = priv.CanEdit(anotherArticle, _author);

Assert.IsFalse(result, "Should not have access to others' articles.");

}Most systems have a fairly discrete number of actual privileges – far fewer then the total number of IsInRole() checks that are littered throughout the code (often at both the UI and business layers, if not the data layer). By adding the abstraction of a Privilege to the system, the amount of work required to introduce new roles or to apply authorization logic based on things other than roles (e.g. ownership) becomes much simpler and centralized.

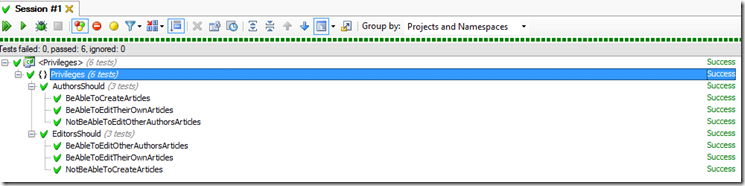

After adding additional tests for editors, which in this case we’re saying can edit any article but cannot create them, you get results like this:

You can download a sample project showing the above code in action here. Please let me know if this helps you to improve the design of your application, or if you have any suggestions for improvement on this approach.

If you found this helpful, you should follow me on twitter and subscribe to my weekly dev tips.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.