3 Tips to Improve Your Connection Strings

Date Published: 30 September 2011

Due to some database moves, I’ve recently been touching a lot of connection strings, which has me thinking about the topic. In fact, I put togethera short surveyon twitter, and invited a bunch of developers and DBAs to share their thoughts, both on twitter and in the survey, on some issues relating to connection strings. Here are three tips you should know about that, if you’re not already using, should improve your use of connection strings.

Use Windows Authentication (if you can)

By far the biggest tip I can offer is that you should be using Windows Authentication. You can find this guidance directly from Microsoft, when they discuss Choosing an Authentication Mode on MSDN/Books Online. Here it is, in their exact words:

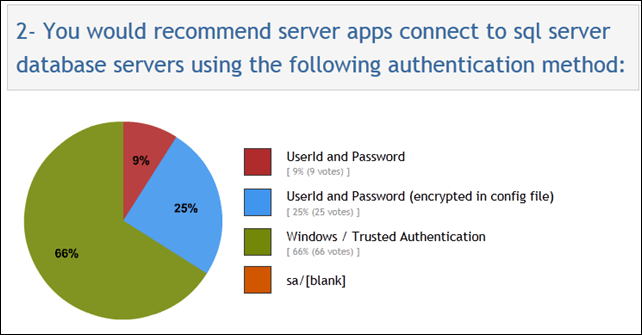

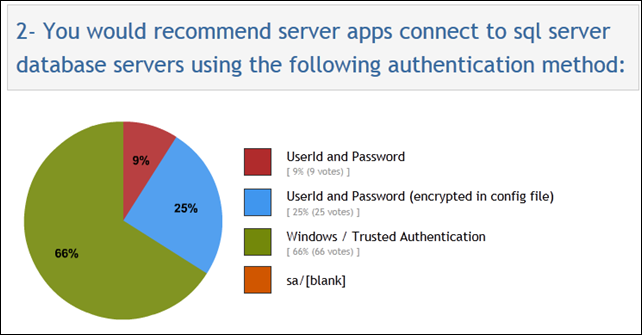

Why is this preferred? Because the user’s credentials are never sent over the wire. “Windows Authentication is the default authentication mode, and is much more secure than SQL Server Authentication.” From the poll I conducted, it seems that most folks do realize that Windows Auth is the way to go, with fully 2/3 of respondents going that route, and another 25% trying to mitigate the security issues of Sql Authentication by at least encrypting the connection strings within the config file:

What are the downsides? Well, it only works with Windows machines, and not across domain boundaries, are the two biggest ones. There are rumors about performance issues with Windows Authentication, but as far as I can tell,these are without merit. Here’s one thread that explains why even in a worst case scenario, there shouldn’t be any noticeable performance difference between Windows Authentication and SQL Authentication. The main reasons given by Microsoft why you might choose SQL Auth are:

- Support older applications and those that require SQL Server authentication.

- Support mixed operating systems, where some users are not authenticated by a Windows domain

- Allow users to connect from unknown or untrusted domains.

- Allow SQL Server to support Web-based applications where users create and connect as their own identities.

- Allow software developers to distribute applications using a complex permission hierarchy based on known, preset SQL Server logins.

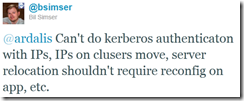

Unless one of these applies to you, use Windows Authentication. Here are a few more responses from Twitter:

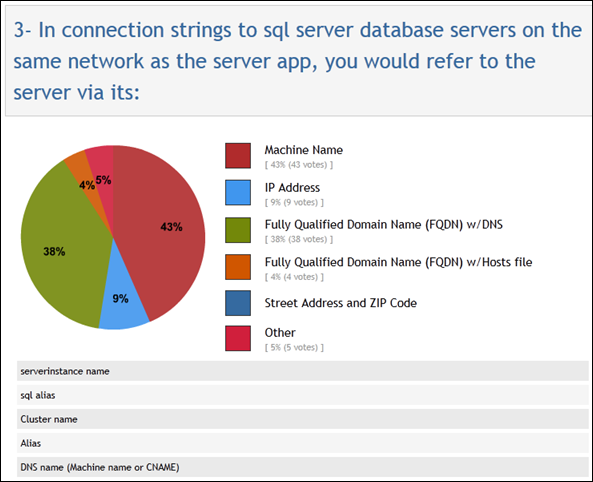

Use a Fully Qualified Domain Name for your Database Server Name

Sometimes, your database will need to move from one physical server to another. Similarly, sometimes a web site will need to move from one web server (or hosting center) to another. In both cases, client applications need to be able to connect to the database (or web site) at its new location. In both cases, the use of a Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN) for the server’s name coupled with the ubiquitous Domain Name Service (DNS) to translate this name into an actual address (IP address) makes it unnecessary for the client to make any change as a result of the move. If, instead of using a FQDN, you connect to your database’s server by referring to its machine name, or worse, its IP address, then any time the database needs to move to another physical machine, you will need to update every connection string on every application on every machine that references this database. Depending on the scope of your operation, this can quickly turn into a significant amount of work. From my survey, about 42% of respondents recommended using FQDNs, with another 43% saying they would use the server’s Machine Name. Just 9% would refer to the server via its IP Address, something I would personally call a worst practice (I speak from experience here). Here’s the survey results – I was actually surprised nobody chose the dark blue option just to be snarky:

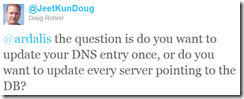

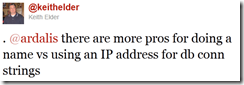

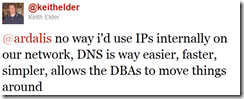

Here are a few more comments related to this question:

It’s also worth checking out Dynamic Update, as Mike Letterle recommends here:

My recommendation is to create a FQDN per database, rather than using something that corresponds to a particular server. For instance, it’s not uncommon to have a separate database for authentication and another one for an application’s primary data. Maybe when your app launches both of these are on a machine named SQL1, at IP address 192.168.0.123. And let’s assume just to make it interesting that your app will run on a web farm with N web servers, so any time you need to make a change, you’re touching at least N config files.

When you specify the server in your connection string, if you use 192.168.0.123, congratulations, you’ve just hardcoded your application to something that can change extremely easily, and you have zero abstraction layer so there is a 100% chance you will need to touch this connection string if either database were to move. If you refer to the server as SQL1, then at least the IP address can chance and your app can still connect. But what if you upgrade to a bigger server and move the databases over to the creatively named new server, SQL2? Now you’ll need to update that connection string… bummer. So now what if you refer to the server as sql1.mydomain.com, which is a FQDN, for both databases? Now you’re safe from IP address changes as well as machine name changes, as long as you’re ok with the idea that the FQDN sql1.mydomain.com might actually point to an IP address that is bound to a machine named SQL2.

But what if your application is reaching the limits of what one database server can handle, and you need to split the authentication database to one database server, and the main application database to another (or let’s say it will stay on SQL1). Now, again, you’re going to have to go and touch config files and edit connection strings even if you’re using a FQDN to refer to the original database server.

Now, consider if you refer to your server names with FQDNs that map to each database. For the authentication database, you refer to it as auth.db.mydomain.com and for the cool application you refer to it as coolapp.db.mydomain.com. Now of course in DNS both of these map to 192.168.0.123 initially. If you move everything to SQL2 with a new IP, you can simply change both records. If you split the databases, you just change one record to reflect the IP of the new server. You have the ultimate in flexibility and everything is neatly abstracted so that a change in the location of a resource in your network can be managed at the level where it makes sense – using network tools (DNS) rather than impacting every application that depends on the resource.

And if for some reason it’s beyond your reach to have an internal DNS resolve FQDNs for you, it may still be worthwhile for you to follow this practice, but simply store the mapping between FQDNs and IPs in each of your application/web servers’ hosts files (located in c:windowssystem32driversetchosts). The hosts file is checked before external DNS is, so anything you specify in there will be used by that machine when it maps FQDNs to IPs.

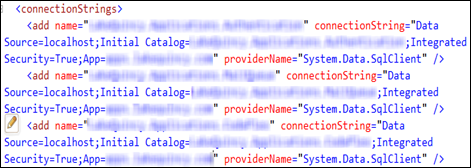

Include Your Application’s Name in its Connection String

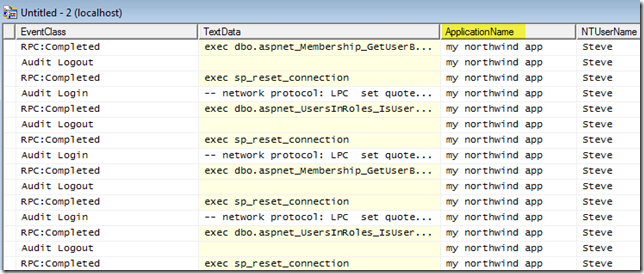

Rob Sullivan was nice enough to point me to this tip, which he’s blogged about in the past. If you don’t include an Application Name= or App= parameter in your connection string, typically the only thing you will see in a tool like SQL Profiler is “.NET SqlClient Data Provider” for every data connection coming in via ADO.NET. Once you add in the App= parameter, you’ll see your actual application name, instead. For instance, adding “app=my northwind app” results in a SQL Profiler result that looks like this:

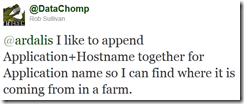

If you’re running a server that a lot of different applications are talking to, this can make it much easier to determine where the various queries are coming from. Also, if you have a cluster or web farm environment, you can include the hostname of the machine as part of the application name (yes you can get this via other columns, too, if you don’t do this), as Rob also suggests:

Just like that, no more mystery involved in determining where various connections and queries are originating. In the past, I had solved this problem by using SQL Authentication and making each application have its own SQL Server login. However, with this tip coupled with the first one above, that’s no longer something I would recommend or endorse.

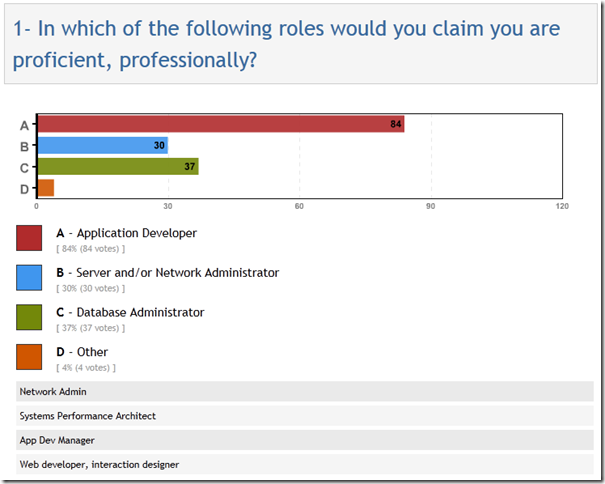

For the sake of completeness, here’s the answer to the first question from the survey. I was hoping I could use these responses to slice the data and see how the answers to the other two questions varied by user role (app dev, DBA, sysadmin), but unfortunately that didn’t work out – maybe next time.

Thanks to everyone who took my little survey and also participated in the discussion on Twitter. I learned a few new things that I’ve already started to implement, and I hope this summary helps out other application developers and SQL Server DBAs who work with them/us.

Category - Browse all categories

About Ardalis

Software Architect

Steve is an experienced software architect and trainer, focusing on code quality and Domain-Driven Design with .NET.